“In this age few tragedies are written. And yet the plays we revere, century after century, are the tragedies.”

So wrote Arthur Miller in 1949, the year he debuted his masterwork Death of A Salesman. More than half a century later, in the centennial year of his birth, we celebrate this great American playwright’s courage and dedication to write modern tragedies—tragedies that defined his age. An uncompromising humanist and moralist with an unflinching quest for truth, he tackled the huge themes of guilt, betrayal, and responsibility for one’s fellow humans, both within the family and the broader context of the human polis, as the Greeks did before him.

This fall, three rich revivals of his tragic works, helmed by directors of boldness and insight, have shown us just how enduring and universal his modern tragedies are.

First, in September, came People’s Light & Theatre Company in Malvern, Pa., which presented All My Sons (the full run was Sept. 9–Oct. 4). This iconic postwar work was only Miller’s second attempt at playwriting, but it brought him a Tony and a Drama Critics’ Circle Award, and, perhaps more importantly, forged a professionaly relationship with director Elia Kazan. Its well-known plot centers around the Keller family and its quest for the American Dream, led by the patriarch Joe, a Midwestern airplane engine-parts manufacturer who hides an inconvenient truth about his factory’s defective cylinder heads to ensure his financial success, his legacy, and his son Chris’s future. When the terrible secret is revealed, Joe must face his responsibility for the death of many American pilots, including his other son Larry.

For People’s Light’s producing director Zak Berkman, Miller’s play resonated strongly with another American classic his theatre had just produced, August Wilson’s Fences. So he asked director Kamilah Forbes to direct All My Sons with an entirely African-American cast, employing many of the same actors from the Wilson production. “There is a strong dramaturgical thread from All My Sons to Fences regarding the American Dream,” Forbes told me.

The result was a deeply moving, otherwise traditional revival that transcended the characters’ race and underscored Miller’s universal themes. The set of white clapboard houses, designed by Troy Hourie, offered an idealized American neighborhood that could be inhabited by any ethnic or second-generation immigrant group striving for a better tomorrow. Michael Genet as Joe and Melanye Finister as his wife Kate led a strong cast who played their roles with passion and conviction.

“There’s got to be something bigger than the family,” says Kate in the end, and Joe realizes that it wasn’t just Larry whose death he’s culpable for but the deaths of “all my sons.” As such, the fall of the house of Keller echoes so many Shakespearean and Greek tragedies, with their themes of hubris and guilt swelling out from a single household to encompass a whole interconnected society.

Miller returned to the theme of betrayal in his powerful 1955 play A View from the Bridge. Written just after The Crucible, it can be read in part, like that play, as a response to the traumatic events surrounding the Red Scare and the House on Un-American Activities hearings, a contemporary American Inquisition that resulted in the terrible naming of names (which, among other things, strained Miller’s relationship with Kazan).

Based on a true story, A View is the account of an Italian-American, Eddie Carbone, who toils at his job on the Brooklyn docks and provides for his wife Beatrice and her orphaned niece Kate, of whom he unnaturally overprotective. The tenuousness of this family’s existence is thrown off balance with the arrival of Marco and Rodolfo, Beatrice’s cousins from Italy—illegal immigrants who come to live with the Carbones. Rodolfo is blond and artistic, and the mistrustful, macho Eddie takes an instant dislike to him. Rodolfo soon takes a romantic interest in Kate, and Eddie’s uncontrollable jealousy soon erupts into violent rage.

View is a play about work, family, the immigrant experience, generational values, and what it means to be a man and survive in America. The daring Belgian-born director Ivo van Hove has given it a sensational revival, which originated at London’s Young Vic last year, transferred to London’s West End, and has now come to Broadway in a coproduction between Lincoln Center Theater and Scott Rudin (it runs through Feb. 21). An unorthodox director known for his radical interpretations of the classics—including controversial productions of Moliere, Williams, and Hellman at New York Theatre Workshop over the past few decades—van Hove’s signature blend of fearlessness and extravagant theatricality works best when applied to tragedy, as evidenced by his five-hour powerhouse marathon of Shakespeare’s Coriolanus, Julius Caesar and Antony & Cleopatra under the title Roman Tragedies two seasons ago, and by his stately Antigone this fall, both at Brooklyn Academy of Music.

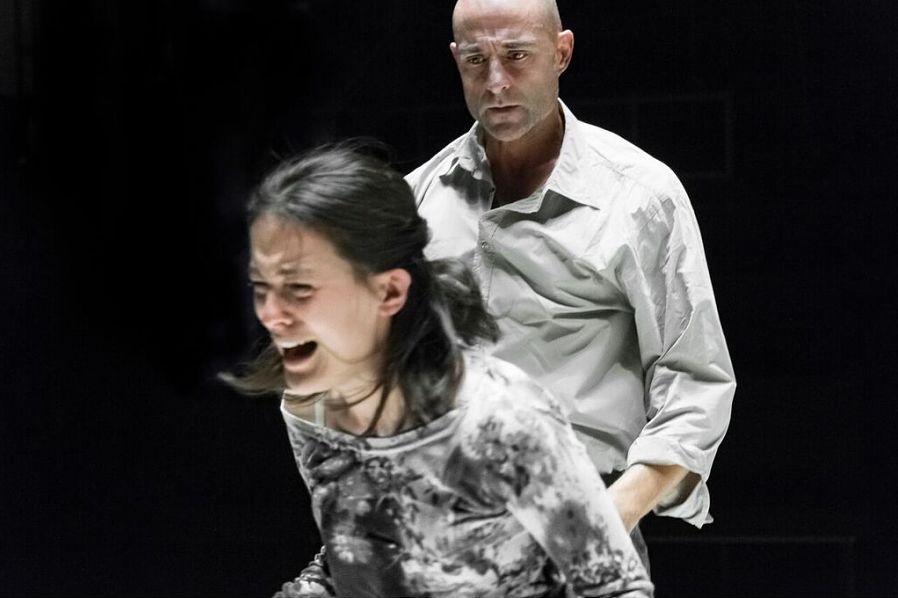

Accordingly, his View is the equivalent of a theatrical tsunami. From the moment designer Jan Versweyveld’s huge curtain-cube rises, revealing Eddie and a coworker washing after their shift at the docks, this ferociously paced production holds us in an iron grip. To the continuous strains of Fauré’s Requiem, the Carbones play out their violent family tragedy on an empty stage surrounded on three sides by an audience who is swept along on this tragic tidal wave of tragedy. In the play’s shocking penultimate tableau, the ensemble members lock arms, while a torrent of blood showers them from above and the cube comes down, shrouding them with deathlike finality.

As Eddie, Mark Strong gives a fierce and unforgettable performance. His sleekly shaved head and sinewy body radiate the brute force of a man determined to survive at any cost. As an affecting Beatrice, Nicola Walker provides dignity and moral force, while the rest of the ensemble rallies to evoke a tragedy worthy of the houses of Atreus and Agamemnon. Michael Gould as the lawyer Alfieri serves as a Greek chorus, underscoring Miller’s adherence to the tragic form.

Meanwhile, the real discovery of the Miller centennial season thus far is the rarely performed Incident at Vichy, given an impeccable production New York’s Signature Theatre Center (through Dec. 20). First performed by the short-lived Repertory Theatre of Lincoln Center at the American National Theatre and Academy (ANTA) in 1964, the play has since been performed only sporadically, owing to its 17-member all-male cast and controversial political content (it was banned in Moscow and wasn’t produced in Paris until the 1980s). The play is largely unfamiliar to American audiences, having had only one New York revival in 2009 by the Actors Company Theatre (TACT).

Set in the Nazi-occupied French capital of Vichy in 1942, the play gathers a group of men detained by local French authorities. One by one, they face interrogation by a sadistic Nazi “professor” and his cohorts. Though the words are never spoken, Miller is portraying the notorious “Office for Jewish Affairs,” created by the Vichy government in collaboration with their occupiers; its job is to round up local Jews and ship them to concentration camps. In addition to the French detainees, the dramatis personae include Nazi officials and cooperating members of the French police force.

In this severe, Sartre-like room of “no exit” (designed by Jeff Cowie), we get to know the detainees: a nervous artist, a Communist electrician, a terrified actor, and an innocent boy, among others. All of them face the humiliating physical examination by their captors to reveal whether they are Jewish or not, thus determining their fate. “It’s a play in which there are a lot of ‘-isms’ flying around,” said director Michael Wilson, referring to the urgent political debate that rages between the desperate detainees as they await their fate. “But the play has a deep well of humanity, and Miller is asking very basic and deep questions—namely, what is it that makes us human? And how can we hold onto our humanity in a world where empathy, sympathy, honor, and decency are in peril?”

The power of Miller’s play lies in his compassion for the moral struggle faced by everyone in the room, captors and detainees alike. A local French restaurant owner who serves Nazis their lunch during the interrogations has an opportunity to save one of the innocent detainees, an employee. Will he take it? A German major must choose between obeying orders or losing his job. What will he do? “There are no more persons,” the major (an anguished James Carpinello) finally cries out, giving in to the inexorable tide of man’s inhumanity toward his fellow man into which he is swept.

Darren Pettie as the brave psychiatrist, Jonathan Hadary as an old Jew who, like a Greek chorus, reads from the Bible in Hebrew, and Derek Smith as the traumatized actor contribute to the crescendoing chorus of desperation. At the culmination of the play’s 87 agonizing minutes, directed by Wilson with brilliance, clarity, and sensitivity, the stage is emptied of all its sufferers save two: an Austrian prince who was wrongfully detained, and the psychiatrist, whose attempts at organizing an escape have failed. The prince has just been given a note of discharge by the interrogators to show to the guard at the door: Will he use it to save himself? It is the final opportunity for one man to take responsibility for the life of another, and the prince (played with heartbreaking humanity by Richard Thomas) takes it. That blinding moment of light is immediately followed by a frightening coup de théâtre: The empty stage goes suddenly dark, a deafening sound is heard, and a speeding train hurls into the future with horrific symbolic significance.

“In tragedy, and tragedy alone,” wrote Miller, “lies the belief, optimistic if you will, in the perfectibility of man.” It’s as if all of Miller’s writings, over the three decades in which the above three plays were written, built to that heroic penultimate moment in Incident at Vichy in which one man displays courage, honor, decency, and compassion. This is Miller’s legacy, finally: the hope that, against all odds, human beings will somehow still strive for that perfectibility in our troubled world.

“It’s not enough to feel guilty and to weep,” said Wilson. “Miller is saying we must step forward and do whatever is in our power to do.”