I didn’t realize that Lynn Manning was blind as I watched him perform in The Central Avenue Chalk Circle. A tall, striking, bald, besuited black man, Manning was playing a sinister rebel senator in his own dystopian contemporary adaptation of Brecht’s Caucasian Chalk Circle, and he moved across the stage throughout the performance with confidence, even swagger. Only at the end, I think, when he struggled for a moment to find a castmate’s hand for the curtain call, did I suspect his vision was less than perfect.

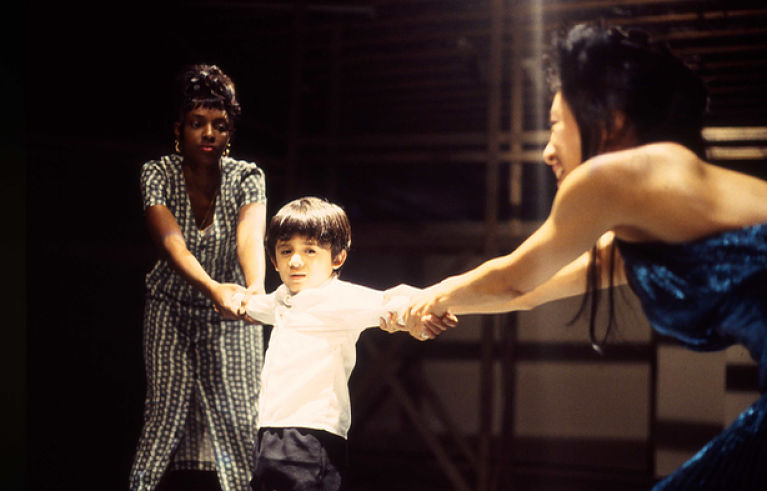

The whole blessed, moving, hard-edged carnival of a show—staged exactly 20 years ago last month as the culmination of Cornerstone Theater Company’s historic play-making residency in Watts—was full of unlikely miracles like that. At one point a sedan drove startlingly into the far end of the warehouse-like space of the Watts Community Labor Action Committee; armed men jumped out and snatched a toddler, then squealed away. Neighborhood kids in the audience marveled as other neighborhood kids sang Shishir Kurup’s haunting “Mother” refrain, with which the abandoned baby of an assassinated L.A. mayor and an oblivious socialite mother woos Gertha, the tetchy maintenance worker literally caught holding the bag, into claiming the child as her own and risking her life for him. Performers entered from all sides of an exposed-wood scaffolding structure that tripled as set piece, catwalk, and audience riser; if I recall correctly, we could feel the performers as they ran and jumped on and off and across the staging area (I could be imagining that detail, but that should give you an idea how vivid and immediate it all was). The audience roared back at the characters’ extreme choices and dramatic reversals; they mmm-hmmed and amen-ed at the funny, gritty, contrarian worldly wisdom of Brecht as filtered through Manning (Eric Bentley was credited as a co-adaptor, as Manning used Bentley’s translation). A live band dominated by frisky congas kept things cooking along.

It was the best show I ever saw.

When I tell people I caught the theatre bug in L.A., I usually feel the need to explain, or at least say more. And it’s not just the world-beating work I saw on the now contested 99-seat stages there, or the ambitious international stagings at the short-lived city-run version of Los Angeles Theatre Center (which included Reza Abdoh, Culture Clash, and Stein Winge, among many others), or the remarkable run Center Theatre Group had in creating nationally significant work in the early ’90s (Angels in America and The Kentucky Cycle being just the two most prominent examples).

It also had a huge amount to do with Cornerstone, a once-itinerant troupe that settled in L.A. in 1992, not all that long after I did. Founded by a bunch of impossibly idealistic Harvard grads who wanted to make theatre, and social impact, well outside the established resident theatre culture, they initially traveled the country to make plays with and about communities with little or preferably no theatre traditions. Their settling in L.A. was in part a way to continue making theatre outside the established theatre culture—because, by some lights, of course, that film/TV town can too easily be dismissed that way—and partly, as I understood it, to come to the country’s most multicultural metropolis and create as many different kinds of theatre with as many different kinds of people as possible, as well as diversify their own all-white company. (They might have accomplished the same things in Queens—just sayin’, guys.)

One thing I came to love about their work, as well as them personally, was their curiosity and fearlessness. In a rigidly segregated and atomized car town, Cornerstoners were (still are) eager to bridge the divides between Beverly Hills and Boyle Heights, between Pacoima and Watts, and among religions and classes and ethnicities (as they’ve defined “community” in manifold ways). In a very real sense, they helped showed me my own city—a sprawling accordion of exurbs, really, that for nearly two decades drove me nuts, intoxicated me, and made me want to crack its sand-written codes. The 1990s, in case you don’t recall, were like a four-horsemen parade in the Southland: riots, fires, mudslides, Northridge quake, O.J. Among the things that Cornerstone did was to help me discover the infinite facets of that polyglot place in off-the-beaten-track ways that you’d never find on any tourist brochure or star map.

While this is in fact generally true of the farflung theatres to which I drove to see stage work, from Ventura to Garden Grove and all points between, Cornerstone made their work in the communities they did for deeply intentional, hence indelible reasons. I’d been to Watts at least once before to see the famous towers, but when Cornerstone did a years-long residency in the neighborhood in the very midst of the fraught, apocalyptic ’90s, they lured me into neighborhoods and locations I might have only driven by on the way to somewhere else, if at all. And once I got there, I came upon lovingly hand-crafted theatre events, some more polished than others, all made with, for, and about the communities in which they’d embedded.

They also did occasional professional ensemble shows: non-community-based productions cast only with their own company’s actors. These weren’t too shabby, either: In a makeshift space in the Santa Monica Place Mall, for instance, I especially relished the diverting Malliere and the wrenching A California Seagull. As those titles might indicate, though, Cornerstone’s concerns were always resolutely in the here and now—or in playing on and stretching the often tenuous rope bridges we walk between here and there, and then and now.

As I wrote years ago, what Cornerstone shows taught me, apart from any L.A.-specific tips (Liliana’s tamales in Boyle Heights are amazing; the L.A. Central Library has many more opulent rooms than you’d suspect), was that

One of the subtexts of every play is the story of the audience and the actors onstage, the theatre space, that night in history, the neighborhood, the city where it’s happening, the sirens whirring by. The ephemeral coincidence of all these things around a theatre activity at a specific time and place is a part of a play’s meaning, however subconsciously. Cornerstone shows tend to bring that subtext aboveground and hold it up to the light; they make it hard to avoid noticing where we are, who’s onstage, who’s next to us in the audience, not just because all these may be novel to us but also because specificity of time and place is a central element of Cornerstone’s work, from its casting of non-professional community volunteers to its typical insistence on finding or fashioning a venue accessible to that community.

Lest it sound like they only did crowd-pleasing, pandering, make-work theatre—well, occasionally their shows had far better intentions than execution, to be honest. But not very often. And certainly not with Brecht’s Chalk Circle, which Manning used to hold a cracked, alternately mocking and loving mirror up not only to Watts, a community as much defined by its historic black population as by its longstanding and ever-growing Latino demographic, but to California and to complacent Clinton-era America, as well. As in the original, our sympathies started and settled with members of the underclass, buffeted by war, police brutality, gentrification, toxic politics, the supremacy of the gun, garden-variety greed. But also as in the original, most of these lumpenproles appeared as susceptible to prejudice, avarice, and bad faith as were the elites; they just didn’t have as much as access to power.

That power differential can make all the moral difference. The whiplashing paradox of striving for good in a terrible world, which is the subject of The Good Person of Szechwan, is crystallized entertainingly in Chalk Circle’s Azdak, “Magistrate for the Masses,” played in Central Avenue by Kurup as a peremptory hippie wino sage with a lecherous edge and a cutting wit. In Brecht as in Manning, this unholy fool almost invariably rules for the underdog, but does so for all the (ostensibly) wrong reasons: appropriated food, drink, property, whim, pique.

That a bad person might do good, and vice versa, is something we still have a hard time facing, even in our fictional narratives. It is not only the religious among us who instinctively look for angels and devils—universal explanatory culprits and “it’s so simple” solutions—in response to the thorny conflicts that greet us daily. That’s a message I was as grateful to be confronted with amid the existential tarpit of ’90s L.A. as I am to reconsider today as I contemplate Beirut, Paris, Charleston, San Bernardino.

Cornerstone continues its tradition of pathbreaking theatre to this day. That, and the fact that many Cornerstone-bred artists, including cofounding members Bill Rauch (who directed Central Avenue) and Alison Carey, are either working full-time or at least some of the time with the resident theatres they once eschewed, transforming them in the process—and that once-dormant Watts Village Theatre Company, a troupe founded in the wake of Cornerstone’s residency, seems to be back up and running—gives me hope not only for the theatre but for our nation, indeed for the entire human civilizational project. It’s hard not to wonder sometimes: Does the work we do and care about have meaning? It most certainly did on a pleasant November night in 1995 in Watts, an evening which, far from spoiling me for other less revelatory theatre experiences, opened my eyes to irreducible truths about this art form I still feel lucky to cover—truths, and signs of hope, that are always there if you look for them.