There is a small but far-flung community of artists whose prime directive it is to stage stories that transcend time and space and venture to other worlds. You can find them at the Stage the Future annual convening, being held this year in Louisville, Ky., talking about bringing supernatural and seemingly impossible narratives to the stage. In L.A., the annual Sci-Fest brings together theatremakers to celebrate the genre.

Otherworld Theatre in Chicago, The Navigators in Buffalo, N.Y., and Science Fiction Theatre (SFTC) in Boston are all part of this niche network, and they are working together to expand the pool of science fiction and fantasy theatre writers, with a special emphasis on diversifying what is often a male-dominated genre, as well as broadening the audiences beyond either just theatregoers or just sci-fi fans.

“It can sometimes feel like it is you against everyone, because the genre is, I guess, against the grain of what people expect when they go see theatre,” says Tiffany Keane, Otherworld’s artistic director. Keane credits her fellow science fiction theatres for helping to “plant the seeds and help the genre grow.”

“When you have a science fiction play, that is also just a good play, you get everybody on board,” says Bella Poynton, artistic director of the newly founded company the Navigators. “But people see sci-fi on the page, and they have a reaction to it—they have preconceived notions of what that means.”

For SFTC, now in their 5th season, the audience is made up of a mixture of theatre lovers, sci-fi enthusiasts, and nearby MIT students. Kelley Holley, SFTC’s director of new work, notes that theatre is even used by scientists at Harvard to communicate the results of scientific studies. And Poynton says she noticed that younger audiences, predominantly teenage girls, were in attendance at a recent show at the Navigators. Otherworld’s first production, Farenheit 451, attracted Ray Bradbury fans who have since become regular attendees.

In addition to attracting diverse audiences, all three theatre companies aspire to bring new voices into the mix. While stage adaptations of science-fiction novels have fared well with audiences, new-play development and readings are at the forefront of these theatres’ programming. SFTC currently has two resident playwrights, both women, one of whom is writing science fiction for the first time.

“One of the things that science fiction is so great at is exploring possible utopias,” says Holley. “And that is a way to show diversity and to represent underrepresented voices…both onstage in our communities and in science fiction. Science fiction certainly has female voices scattered throughout, but it is such a male-dominated genre that we really want to make sure that we are working toward diversity, and that in our seasons we have at least gender parity in terms of our playwrights.”

Poynton, a playwright herself (her plays have been produced at both Otherworld Theatre and SFTC), knows firsthand how difficult it is to get work produced as a female writer in a predominantly male genre. For the Navigators, she tends to program sci-fi plays with feminist overtones. She says she sees science fiction less as a closed door for female writers than as an opportunity to bring more women into the fold.

“I kind of see science fiction as inherently feminist, because it is looking away and imagining another future,” Poynton says. “That future kind of becomes a feminist future, because it isn’t the one that we are living right now. It isn’t the patriarchy or the ideological society that we are living in here. By virtue of what it is not, it makes it a feminist idea.”

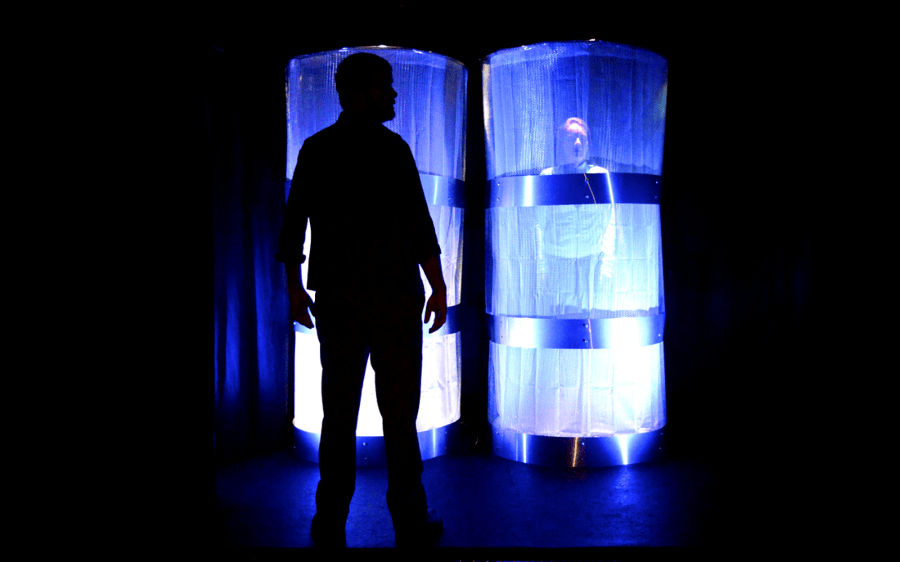

The most challenging part of producing science fiction plays isn’t finding the writers; it’s actually putting these other worlds on the stage. “Science fiction theatre mandates a need for creative thinking,” says Holley. With robots, teleportation devices, aliens, and unknown creatures at the center of the work, imagination is necessary to bring the elements of science fiction plays to life.

“World building is so much fun—there is a sense of wonder every time you get to build new worlds from scratch,” says Keane.

SFTC encourages writers to think beyond the proscenium arch, budgets, and cast size when building their worlds. “One of our core values is that nothing is impossible onstage, and we really want to stage what people can’t,” says Holley. The company has succeeded in staging holograms, spaceships, and, in their most ambitious set piece yet, a man fused to a couch due to a teleportation accident.

But with the proliferation of sci-fi on TV and in movies, science fiction theatremakers are often asked: Why theatre? That’s the question wrestled with every year at the Stage the Future gathering, but there’s also plenty of discussion of how, with conference attendees comparing notes on puppetry, lighting, projections, and other stage techniques to help audiences suspend disbelief.

“The biggest myth I would like to dispel about producing this genre is that it is so expensive,” says Keane. “People assume realism is so much cheaper than science fiction,” says Keane. For Otherworld’s production of Farenheit 451, for instance, Keane repurposed old books for the set.

“The magic of theatre is that anything is possible,” she says. “In realism, if you have a living room set, everyone knows what that should kind of look and feel like.” For Otherworld’s production of Poynton’s The Aurora Project, Keane recalls creating a textured plastic wall covered in bubble wrap, an innovative and cost-effective way to transport the audience into another, futuristic reality in which, as she puts it, “this is what a wall looks like.”