264 pp., 40.00 paper.

Anyone with a basic understanding of theatre production is already aware of its laborious demands. Instead of reexamining common knowledge or becoming a compendium of Marxist critical readings, this new collection of scholarly essays attempts to lay out many new paths for exploration into the field and history of theatre makers. Editors Osborne and Woodworth show that there is much to be discovered.

Unfortunately, the overarching questions the editors set out at the beginning of the text give them a nearly impossible agenda, since their queries are so vast that no reasonably sized anthology could hope to contain them. This foreshortened attempt at universality leaves the collection feeling a bit scattered. Fortunately, while the book may set itself too high a bar for an academic publication, its actual content is consistently interesting. If one imagines each essay as a trailhead into a pathway of theatre history they haven’t rigorously considered before, then this is a text rich with beginnings. Those who want a text that will lead them to a thousand other texts will be right at home. Those looking for something beyond the writer-director-actor triumvirate that constitutes so much theatre criticism will be glad to see their interests broadly honored. But those hoping for a unified critical mode must look elsewhere.

Working in the Wings is divided into four broad categories, each of which contain three or four separate essays. The first section, “Working Conditions,” explores the theatre artists “who work behind the scenes to bring a performance to fruition.” It starts with “Driving Race Work: The UAW, Detroit, and Discrimination for Everybody!” The essay situates the highly progressive play Discrimination for Everybody! within the complex and nuanced cultural context of its post-war premiere. The script elucidated an economic argument for civil rights, which the United Auto Workers advocated in 1949.

The next essay, “Working Together: the Partnership of Les Waters and Annie Smart,” is a powerful exploration of the personal and professional partnership between Waters, a director, and Smart, a costume and set designer. The essay explores the ways their work and homes blur together and actually strengthen the creativity and autonomy of each artist. The essay also offers a strategy for scholars to make equitable critiques of interpersonal dynamics within public work. While the text feels a bit like an introduction to a full-length book, it is a book worth watching out for. Moreover, given how artistic and interpersonal worlds comingle in our field, this essay is something every college theatre major should encounter early on.

The next essay moves from the intensely personal to the unexpectedly capital, as “Advertising and the Commercial Spirit: Cataloging Nineteenth-Century Scenic Studio Practices” uses sales catalogs to explore how the development of off-site set construction and affordable rail shipping changed the nature of theatremaking in America. While such an exploration may seem esoteric, given the radical ways technology is again changing our discipline, the essay contains some highly prescient research and invites us to resist a binary between art and craft. Simultaneously, the research recovers some of the lost history of manual labor in the theatre. The last text in the section, “Don’t Quit Your Day Job: Situating Extratheatrical Employment in the Performance Archive” contrasts the day jobs of actors Neysa McMein and Kitty Marion while situating both women within first-wave feminism. The essay explores a question of deep relevance to most theatre makers today: “What is the relationship between paid and unpaid work completed away from the stage and that which is done onstage?”

The second section of the collection, “Inscription, Erasure, and Recovery: Palimpsests of Labor,” is more focused and contains essays exploring the recovery of marginalized and forgotten voices. The section starts with a nuanced work, “Retooling the Kitchen Sink: Representing Domestic Labor in American Performance After 1963.” This essay explores two political works on women’s domestic lives, Martha Rosler’s Semiotics of the Kitchen and Sara Ruhl’s The Clean House. The essay shows how “housework and cooking are both a trap and a haven” [author’s emphasis] in a lucid way that rises above easy paradox or simple dichotomy.

“Beaten, Battered, and Brawny: American Variety Entertainers and the Working Class Body” moves the section from an exploration of domestic labor to the representation of blue-collar labor on the stage. The text looks at the way performers of the tramp clown, the sideshow freak, and the strong man offered ways for working-class audiences to manage their anxieties in the dangerous and heavily mechanized workplace of the early 20th Century. The discussion of the strong man Eugen Sandow is particularly astute in connecting the beauty and strength of physical labor to a subtext of victory over mechanization.

The section’s next essay is a necessity in a collection like this one: “Hidden in Plain Sight: Recovering the Federal Theatre Project’s Caravan Theatre.” Since the New Deal and reactions to it shaped so much of the subsequent century, it must be touched on, and so it is touched on here, and smartly. The essay suggests “a way to decenter modes of thinking about [Federal Theatre Project] activities” and look at them in a national and sociopolitical context. Shifting away from the grand scope of New Deal politics brings the final essay in the section, “African-American Waiters and Cakewalk Contests in Florida East Coast Resorts of the Gilded Age,” wherein the essayist situates the performance of the cakewalk as a “transitional step” towards the acknowledgement by white elites that African-American culture actually exists.

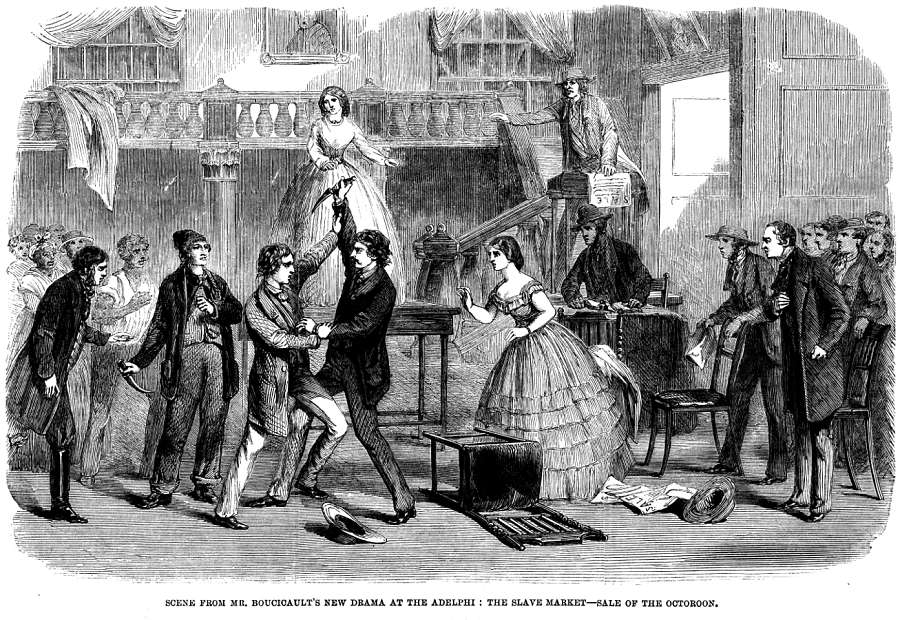

The third section, “Myth, Memory, and Manifestation: The Work of the Public Mind,” looks at how theatre reshapes identity and the “public imagination.” The section begins with “Dion Boucicault’s The Octoroon and the Work of Republicanism.” The essay argues that the show was designed to draw reactions from both sides of the slavery debate during the fractious time between the execution of John Brown and the election of Lincoln. The essayist shows how scholars and critics built corollaries between the play’s protagonist and John Brown, and how the script’s intentional ambiguity invited audiences to do so.

Moving to an earlier moment in the creation of national identity, the essay “Myth Made Manifest: Labor, Landscape, and the First Washington Theatre” provides a history of the construction of the first theatre in the nation’s new capitol. The fundraising for such a project was both democratic and populist, in the spirit of the young nation’s ideals—if not its practices. This parallel vision of democracy and populism is at the heart of the essay: “They wove democracy into their playhouse’s foundation, expanding the ways in which theatre could manifest American identity beyond plays and playgoing to the building itself.”

The next essay looks at the inversion of that previous democratic ideal 90 years later in “Labor, Theater, and the Dream of the White City,” which explores the erasure of real labor by capitalist propaganda at the Colombian Exposition of 1893. The writer builds to a succinct idea of cultural creation worthy of extensive discussion: “If labor is that common interest, given that all production ‘makes’ something, what is produced by work can be recognized as culture.”

The fourth section, “The Creative Work / The Work of Creation,” examines the labor of creation in and of itself, but comes at that examination from unexpected directions. The section starts with an essay on the inception and growth of the Three Rivers Shakespeare Festival in Pittsburgh, “Blue-Collar Bard: Recalling Shakespeare through the Rhetoric of Labor.” The essay illustrates how the festival’s founder navigated cultural bias to make successful connections between Shakespeare and working class sensibilities. These connections hold lessons relevant for anyone considering the complexities of the relationship between theatre and audience in the new century.

The collection then jumps to a completely different kind of political work in “Songs of Salaried Warriors: Copyright, Intellectual Property, and John Philip Sousa’s The Free Lance.” Here the essayist shows how the famous bandleader and composer used his sizable cultural clout to help get copyright protection extended to music by, in part, writing his comedy The Free Lance, and how he used the notion of individual achievement to make it into a populist case. The final essay moves from populist to subjective with “Working on a Masterpiece: Rinde Eckert’s And God Created Great Whales.” It explores the way Eckert’s play combines obsession and the struggle of creation to examine how “human beings use work to rise above the mundane in an effort to glimpse the divine.”

With that final notion of divinity, a collection that touches on vastly different modes of work steps beyond labor and culture into the spiritual. It is a fitting final essay for a diverse assemblage of unexpected ideas and explorations. This is a useful book to have on one’s shelf.