SACRAMENTO, CALIF.: “Steph and I often discuss what plays are new and hot,” said Jonathan Williams, referring to the very theatrical pillow talk in which he and his wife, Capital Stage cofounder Stephanie Gularte, regularly engage.

It was back in 2012, he recalls, when Gularte—who has since been named artistic director of American Stage in St. Petersburg, Fla.—originally brought up Anne Washburn’s Mr. Burns, a post-electric play, which she thought was an ideal title for the Sacramento company she and Williams oversaw for more than 15 years. But it wasn’t until late last year, during what would be their final season-building confabs, that Williams decided to apply for the rights.

It seemed an apt choice for the opening production of Capital Stage’s 2015–16 “Brave New World” season, a seven-show roster of local and world premieres and original adaptations. With an unusual, time-hopping narrative, a high-profile award nomination (Drama League Award for Outstanding Production), positive national press, successful world and subsequent regional premieres (it’s on American Theatre’s Top 10 Most-Produced Plays list for the current season), not to mention the unrivaled pop-culture cachet of its “Simpons”-related theme and title, Mr. Burns seemed to Williams, in a word, “excellent.”

“It’s an incredible leap of the imagination,” said director Michael Stevenson, who took over as Cap Stage producing artistic director Sept. 1, and inherited the play selection, when Williams joined Gularte in Florida. “I’ve never read anything like it. Anne’s got an incredible mind.”

Indeed, the author of such form- and mind-bending plays as The Internationalist and 10 Out of 12 wondered, in Mr. Burns, what would happen if a series of electromagnetic-pulse attacks or nuclear power plant failures pulled the plug on all electronic devices for good, and contemporary society was forced to retreat to storytelling platforms that predate Roku, amplitude modulation, even movable type.

Washburn further asked herself if, along with hoarded caches of expiration-free, crème-filled snack cakes, humanity would seek comfort in sharing faded yet still familiar cultural memories passed down by recent generations. Might ragtag troupes of amateur actors actually traverse desolate landscapes to trade rival companies for sketchy recollections of “Simpsons” episodes in exchange for jolt-giving consumables ranging from Diet Coke to lithium batteries?

Initially commissioned by New York City’s Civilians for a 2012 premiere at Washington, D.C.’s Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company, Mr. Burns is both a darkly comic paean to Matt Groening’s long-running Fox series and to the fundamental appeal of live theatre. The play opens in an encampment, where a group of literally powerless survivors pass the time by dredging up dialogue and plot points from “Cape Feare,” an honest-to-God fifth-season “Simpsons” episode. The second act picks up seven years later. By this time, an established circuit of real-live “Simpsons” reenactor gangs is routinely staging piecemeal episodes, rounded out with musical numbers and vintage commercials for products that are no longer available. And the third act flashes forward 75 years, by which time the “Cape Feare” episode has become a Greek-style choral tragedy about survival against the odds.

It’s a demanding show in terms of its technical, musical, and directorial demands, but it has proven remarkably popular since its 2013 NYC mounting at Playwrights Horizons. Samuel French, which holds the rights, has been fielding calls from artistic directors from La Jolla, Calif., to Romania, who have come bearing more traditional forms of tender than Duracell “D cells” in hopes of jumping on Washburn’s post-“apopalyptic” pageant wagon.

Washburn, who said that while she has a great respect for “The Simpsons,” conceded that she’s “not a proper fan.” (“I’m not that knowledgeable…It’s still on Sundays, right?”) But she also knows that the TV angle didn’t hurt the play’s visibility.

“I think it got a lot of attention because audiences were aware of the title character,” said the Brooklyn-based Washburn. It’s been her most popular show by far, in fact, which she presumes is based largely on its seemingly easy-to-sell premise of being “a combination of ‘The Simpsons’ and the apocalypse.” And with the hefty musical score by Michael Friedman, she said, theatres “felt like it would be a good title that would bring in younger audiences. Even those companies already boasting younger audiences are saying that it brings in an even younger crowd.”

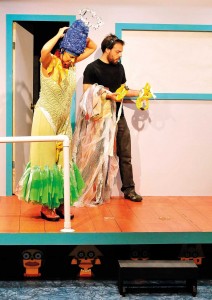

Cap Stage, a 127-seat Equity playhouse in the midtown district of California’s capital, had another affinity with Washburn’s play. The theatre started out as a tenant on the lower deck of the forever-moored Delta King riverboat—and Mr. Burns’s “spectacle” of a third act largely takes place on board a creaky houseboat, here designed by Williams, familiar to fans of “Cape Feare,” as well as the two films of Cape Fear the episode animatedly skewers.

That didn’t mean it would be an easy fit for Cap Stage. Production manager Cathy Coupal said she couldn’t have been happier when Williams announced he had secured the rights—her e-mailed response after receiving the script was,“First read: WTF?! Second read: OMG! Third read: I cannot wait to do this show!”—but she also knew it would present challenges.

“How are we going to realize this in our space?” Coupal said she asked herself. “What specialties will be needed on the production team? Where are we going to get a piano and a glockenspiel?”

Scheduled for a four-week run with previews starting Sept. 2 and a Sept. 5 Saturday-night opening, Cap Stage’s typically fast-paced preproduction schedule provided just a month for Stevenson and his behind-the-scenes staff to put up the show. The initial table read was set for Aug. 11.

“It’s a big show,” admitted Stevenson in a mid-July interview. “There’s the big musical element, challenging ideas, major set pieces and costumes. There are time jumps that will present continuity challenges for the audience, but I certainly hope they get the joy out of the play that I do. It’s exciting to go into new territory.”

For Cap Stage technical director Steve Decker, who also took on the role of lighting designer for Mr. Burns, the biggest challenge was “dumbing down” cutting-edge technology to emulate the play’s off-the-grid look.

“In collaborating with Jonathan, who was designing the sets, we’d discuss ideas on how we’d achieve his vision,” Decker said. “How do we do this post-electric play in an indoor theatre and make it seem like an electricity-free outdoor space? If we weren’t in California, with all these fire codes, I’d simply have the actors in Act 1 holding up candles in front of their faces. But our fire departments are fearful of live flame onstage.”

Ed Lee, a Cap Stage vet since 2008 who served as both sound designer/engineer and assistant tech director for Mr. Burns, had no shortage of ideas when he began his design process.

“I remember writing a number of idea notes as I was still going through the script,” said Lee. “One I thought about was embracing the almost tribal nature of the characters in the final act, and just using ‘natural’ music: percussion, music sung a cappella. It was actually this concept that led me to use a conch shell at one point to open Act III, which evolved into a didgeridoo because the conch sounded too nasal.”

Gail Russell, a full-time theatre arts and fashion instructor at Sacramento’s American River College, and a veteran Capital Stage freelancer, came late to the Mr. Burns party on two fronts. In addition to joining late in the summer because the show’s original costumer was forced to bow out, she admits to not being much of a TV watcher.

“I think not knowing ‘The Simpsons’ put me at a bit of a disadvantage,” said Russell. “I didn’t have any general universal knowledge with people who have watched the series. They knew what the characters looked like, what the personality of the characters were.”

On the other hand, Russell says her streamlined awareness proved to be something of a creative blessing.

“I only had the world of the play to worry about, and in some ways that was good—I could only get hung up on the world of the play,” said Russell. “I thought it necessary to work backward and not forward, as what occurs in the last act is prefaced in the first act. There are cherished things that have been saved.”

Like the actors in Mr. Burns, mask/headpiece artist Larri Russell relied on the discovery of discards.

“I read the script and discussed with Michael the importance of scrounging for materials to create headpieces,” said Russell during the first weeks of her design-and-fabrication process. “I usually scrounge anyway, but it was important to make the pieces look like they were something [the characters] might have found in their time.”

Among Russell’s wins was weaving shredded jeans through the wire frame of an old wastebasket to create Marge Simpson’s sky-high blue beehive. Trial and error is a big part of Russell’s process, with some things kept—a heavenly star representing angelic Lisa’s spiky hair, Sideshow Bob’s wild, faux-fern coif—and other items discarded early on (Homer’s papier-maché headpiece).

“Right now, I’m in the fabricate-or-find-it, fuck-it-up, flip-out-and-fix-it mode,” Russell quipped.

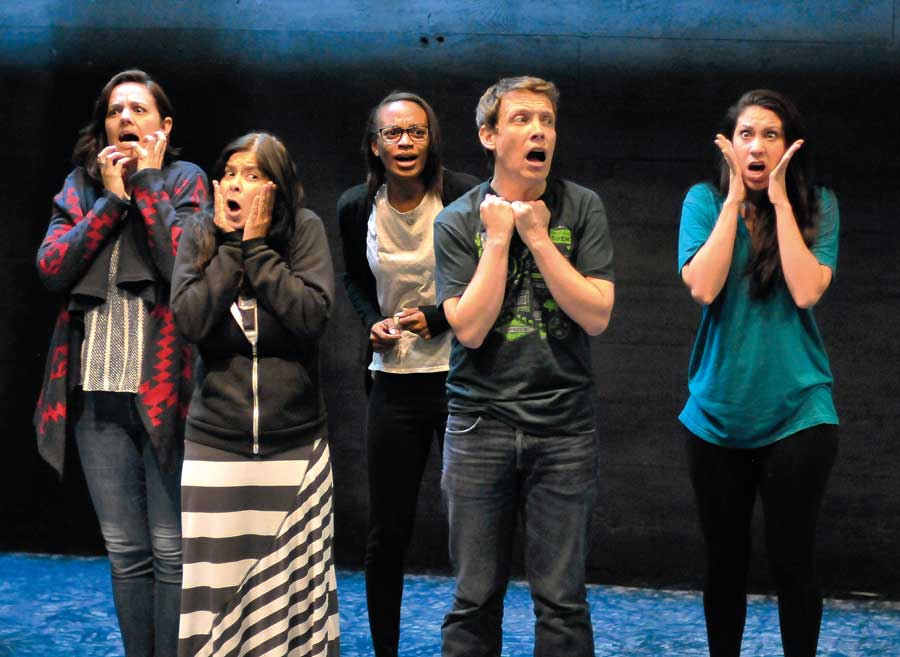

By the third week of July, final casting was announced, signaling the start of a five- to eight-hour, six-day-a-week rehearsal schedule. The cast—John P. Lamb, Katie Rubin, Amanda Salazar, Kirk Blackinton, Elizabeth Holzman, Jouni Kirjola, Tiffanie Mack, and Dena Martinez—was culled from well-known colleagues and familiars, recommended out-of-towners, as well as new-to-Sac actors such as Martinez.

“A lot of people want to work here,” said Stevenson, who added that the several days reserved for general auditions were “very full.”

“After the first read, I was immediately struck by how unconventional and ambitious the script is,” said Lamb, who played Matt as well as Homer and Scratchy. “Three very different acts, challenging and humorous dialogue, a play, a play-within-a-play, and a musical-within-a-play that span close to a century of time in an apocalyptic future. What actor wouldn’t want to dig into this script’s complexities?”

Holzman, who played Mrs. Krabappel, talked about the play’s “meta-upon-meta-upon-meta themes.” Kirjola, who played Sam and Mr. Burns, is a self-avowed “Simpsons” fan since its debut as a series of 60-second shorts featured on Tracey Ullman’s late-1980s variety show; he said he was hooked by Mr. Burns’s opening scene of “survivors of the apocalypse recalling scenes from a ‘Simpsons’ episode. How could you not love that setup?”

But the cast wasn’t universally attuned to the animated series’ appeal. Said Holzman, “Besides the episode that the show centers around, I’m pretty sure I’ve only watched two to three ‘Simpsons’ prior to doing the show.” And Salazar, who played Quincy, confessed, “I didn’t grow up watching ‘The Simpsons.’ My parents thought it was inappropriate.”

Chimed in Rubin: “I’m more of a ‘Family Guy’ gal, myself.”

This scattered familiarity with “The Simpsons,” which might be similarly shared by Cap Stage’s 1,700 subscribers and Greater Sacramento’s single-ticket-buying public, was of some concern to Stevenson, but it was nothing he believed some nimble marketing wouldn’t overcome. “It’s not at the top of my mind, but it’s a consideration,” Stevenson said during a July interview. “It has ‘The Simpsons’ in it, but it’s not about them. It’s really about storytelling and how we cope, and how we go ahead.”

As the days before Sept. 2’s initial preview dwindled, production concepts continued to be refined, with some ideas jettisoned, others rushed into service. To call the process fluid would be an understatement; it was more like a flash flood.

“I’m surprised at how quickly everything popped up,” said technical director/lighting designer Steve Decker. “We ran a little bit short on time. Jonathan wanted to see these totem poles personifying the Simpson family erected onstage in the final act, but it never got truly realized because of time, hands, and resources.”

A compromise was reached, with the visages of the Simpson family embellished by scenic artist Dan Lydersen along the “waterline” of the third act’s major set piece, the “Cape Feare” houseboat.

Part of Russell’s very personal costuming process includes working with her actors and listening to the backstories they’ve written for themselves to provide “integral support in what they’re creating.” Under a bit more pressure than her fellow designers due to the almost immediate need for costumes to accommodate a promotional photo call on Aug. 18, Russell was foraging fast and furiously for found objects, decidedly distressed clothing, and fabrics appropriate for survivor-chic wardrobes.

The pop-music aspect of the “chart hits” scene in Act II, which includes an all-singing, all-dancing, time-warping sequence featuring a mashup of signature moves and choruses half-remembered from the wild YouTube yonder, presented a stumbling block for Russell.

“I had a really hard time with that,” Russell admitted. “I began researching music artists. I had some cultural catch-up to do.” And then, she said, pure luck intervened.

“Amanda (Salazar), who I had worked with in a production of Jekyll and Hyde, came in with this skort as well as this little bustier, and from that I got a visual cue. I reworked the skort that she would wear under the suit she makes her entrance in, and I brought in a denim jacket and cut the sleeves out and started decorating it with found objects. That gave me the idea of the look.”

Russell’s luck continued as she worked on costumes for the post-intermission third act.

“I really liked Marge’s dress in the third act,” she says, noting the patchwork nature of the form-fitting frock that transformed cast member Dena Martinez into the “Simpsons” matriarch, thanks in part to an amalgamation of green plastic bags. “Plastic bags…they’re going to be everywhere forever.”

Concepts were delivered with deus ex machina speed as well, Russell said. Jouni Kirjola’s third-act incarnation as Mr. Burns takes on a scary and silly look inspired by a trio of cartoon villains: His Burns has the receding hairline of Mr. Burns with a pair of satanic, Sideshow Bob red-hued “horns,” and a “big duster coat” costume piece—clearly a lift from the closet of the Joker, the Dark Knight’s dressed-to-kill nemesis.

Much as the art of passing down urban mythology and the stories of choice evolve according to both affinity and necessity in Mr. Burns, so did Cap Stage’s theatrical choices. After the final dress rehearsal, sound designer Lee wondered about an ominous sound design he’d chosen for the opening scene.

“I’m afraid that it’s too dark,” he said. “Hearing something like that may not make anyone comfortable enough afterward to laugh for 10 pages.” A re-edit would probably keep him up late, he admitted, as he’d been sidetracked by a last-minute request for monitors to aid the actors in their singing.

And for costumer Russell, time just ran out. “Distressing and aging fabrics takes time—I just had to let that go,” she conceded.

Not all design struggles ended with sighs of resignation. Some zero-hour lightbulbs did flash.

“Act III is all-moving, all-singing,” said choreographer Shannon Mahoney. “Michael wanted that tribal, repetitive-chanting feel to it. I was really struggling with that. But then I saw it in slow motion. Seeing that moment and others in slow motion added intensity to what they were doing.”

As the opening neared, the cast was also busy making new discoveries and gaining new skills. “I was added to the second act as an extra dancer/singer,” said Holzman. “As the rehearsal process has progressed, I also picked up a number of instruments for third-act accompaniment.”

The Sept. 5 opening-night house overflowed with friends, family, subscribers, and media, as well as newcomers drawn by the novelty of a theatre piece named for a cartoon villain known for, among other things, ordering the release of attack dogs. The first-nighters who spoke to me placed themselves on both sides of the “Simpsons” fandom fence—and felt similarly divided about Cap Stage’s Mr. Burns.

“I was really impressed by what they were pulling off and what went into it,” said Roger Jones, a longtime Cap Stage subscriber. “I thought it was very thoughtful and creative, but I wasn’t as engaged as I usually am by plays at this theatre. I’m not quite sure why.”

Jones, 64, a patron of several area theatres, had some praise to pass along: “All the different styles of music and acting, and the demand on these actors to portray these characters in a post-apocalyptic landscape was pretty brilliant and ambitious. I’d recommend it to people who know ‘The Simpsons,’ or who know a lot of musical styles and maybe dramatic styles.”

Another subscriber, Martha West, a retired University of California–Davis law professor and a Cap Stage subscriber for “four to five years,” calls the company’s shows “very creative and adventuresome.” But West confessed that she was stymied by the theatre’s recommendation to subscribers that they go online to watch the “Cape Feare” episode (“I couldn’t find it,” West said). So she resigned herself to reading a Wikipedia entry to complete her “homework.”

“It required knowledge of pop culture, and I’m not a participant in pop culture,” says West, 69. “I don’t watch TV, and I’m not a ‘Simpsons’ person.”

West did praise the cast, adding that the third act spectacle “redeemed the unexplained horror of the first two acts. It made it more of a spoof. And I appreciated turning ‘The Simpsons’ into a spiritual motif.”

But youth and “Simpsons” savvy didn’t ensure positive feedback, either. Kanishk Pandey, 17, a Davis, Calif., resident who said he grew up with Springfield’s first family, found the play both interesting and “problematic.” The Davis Senior High School senior is not your average theatregoing teen; he’s also an aspiring playwright and the winner of the 2015 Princeton University Ten-Minute Play Contest.

“I was very intrigued by the idea of taking a pop-culture story and turning it into an important story in our history,” said Pandey, who spent the last five weeks of his summer break as an apprentice at Vassar College’s Powerhouse Theater. But while Pandey was impressed by the first act (“Great atmosphere, great world-building, with the characters interacting just right”), the “huge leap” demanded by Washburn’s third act left him second-guessing his interpretation of the first two acts.

“I appreciate the ideas she was playing with, and I think the actors did a great job—you can see all the work that went into it—but how well does the third act incorporate with the point of the story?”

The estimations of Jones, West, and Pandey echoed those of the professional critics. Sacramento Bee writer Marcus Crowder might have rolled his eyes over Washburn’s “overstuffed pop-culture mashup” of a script, and the production’s unrealized “grand ambitions,” but complimented the show’s “polished” cast, and director Stevenson for “pulling complex, cohesive performances” from the multitasking ensemble, especially Lamb, Blackinton, Kirjola, and Salazar.

Capital Public Radio reviewer Jeff Hudson also gave kudos to the cast, dubbing the performances “excellent and beautifully coordinated” by Stevenson. Though allowing that “some may feel the story, stretched over 80 years, is too diffuse,” Hudson said he found the show to be spellbinding, “especially the haunting final act, something I will remember for years.”

Patti Roberts, a reviewer for Sacramento News & Review, ignored the performances and focused on the script, referring to it as “fun, fascinating, fantastical, and often very frustrating.” She directed her criticism at Washburn for overloading her ideas “with too many obscure cultural and pop references while jumbling WTF plotlines.”

The Davis Enterprise’s Bev Sykes suggested that those unfamiliar with “The Simpsons” might be confused by a play that was “riddled with references to the cartoon…I know I missed a lot.”

A week after opening, Cap Stage marketing manager Misty Day said the “marketing engine is running high right now. We are absorbing the first audience and critical reactions to the production, and it has been fascinating to witness the disparate responses folks have been giving us. I definitely feel that we have done our job to start conversations as the ‘theatre for thinkers’ in Sacramento, because people can’t stop talking about the show, whether they were fans or not.”

Still, Day admitted, attendance has “been less successful than last year’s season opener.” Mixed reviews, higher ticket prices, and an artistically difficult show may have played a part in disappointing post-opening sales. “I have been surprised by how many folks proclaim to have no connection to ‘The Simpsons’ whatsoever, which might have some effect as well. On the other hand, we have made extra efforts to reach out to the students and younger population in Sacramento, and their attendance numbers have raised.”

After the fallout of the final reviews settled, Stevenson was of two minds himself, much as local media and first-nighters seemed to be.

“Except for the Enterprise, reviewers said the same thing: They were both intrigued and frustrated by the script,” said Stevenson, who seemed as pleased with what his staff and cast had wrought as he was disappointed that critics weren’t more effusive in their praise. “I didn’t feel the script was overwritten, I was enchanted by it,” he said, referring to a complaint that ran through the Bee’s review. “It’s a very new format, something I’d never read. It’s very dense and very referential, but not in an exclusive way. So the reaction to it caught me off guard.”

For Jonathan Williams, who originally picked Mr. Burns and served as the show’s long-distance scenic designer, the production proved wholly satisfying; he flew in from Florida to catch a few performances.

“I thought it was realized very, very well,” he said, acknowledging that audiences unfamiliar with meta-theatre might have been thrown by the challenging script. “I can’t completely disagree with the criticism, but at the end of the day it’s a play focused on story, not on characters.”

Capital Stage’s next production, Gularte’s adaptation of Ibsen’s A Doll House, may be something of a respite. But the stretching the company did with Mr. Burns may pay off when they produce the envelope-pushing Sacramento premiere of The Behavior of Broadus, an all-out musical about behavioral science and advertising written by the L.A.-based ensemble the Burglars of Hamm; Broadus will play Dec. 9–Jan. 3.

And the audience may be stretched and ready for more: While Williams conceded that Mr. Burns, which closed Oct. 4, fell short of the company’s single-ticket projections, the final weeks of the show saw “a big ramping up. By the end of the run, you couldn’t get in.” To Williams, that said that the play “presented ideas audiences couldn’t immediately process—it’s not a ‘stand-at-the-watercooler-on-Monday-morning-to-gush-over-it’ kind of play. The momentum we saw demonstrated that it needed to percolate in the collective subconscious of the audience. The success of our production is that it overcame its challenges and found its audience. It takes a while sometimes.”

Barry Wisdom is a Sacramento, Calif.–based arts journalist, photographer, and communications professional.