Isaac Butler had long been fascinated by conspiracy theories—or at least, by conspiracy theorists. But it wasn’t until he was in the midst of a brainstorming jag with his friend composer Darcy James Argue that the two hit upon the notion of making a theatre—or rather, a music-theatre—piece on the subject. The result of their work, Real Enemies, debuts at Brooklyn Academy of Music Nov. 18–22.

Butler, a frequent contributor to American Theatre, is also a director and fiction and nonfiction author (and blogger); Argue is the bandleader of the fortuitously named Secret Society and the man behind 2011’s BAM work Brooklyn Babylon. Their collaborators—or should we call them conspirators?—are designers Peter Nigrini and Maruti Evans.

I spoke with Isaac by email last week about his show and got the real scoop on how and why it was actually created, and by whom—because obviously no one’s buying the official story.

ROB WEINERT-KENDT: The first thing I want to know, Isaac, is whether you yourself are susceptible to conspiracy theories, or are you more driven more by the urge to debunk?

ISAAC BUTLER: People don’t usually think of themselves as paranoids: When I believe something it’s because I’ve rationally looked over the facts and come to a reasonable conclusion. When you believe something, it’s because you’re crazy-town banana pants.

When you take a two-year headlong plunge into the history, substance, and psychology of conspiracy theories, you’re also doing a two-year headlong plunge into the history, substance, and psychology of confirmed instances of government wrongdoing. So you can’t help but be a bit more paranoid—or, perhaps, have your preexisting paranoia confirmed.

Part of the terror of starting a large (and long-brewing) creative project is that, in the beginning, it can be anything—really anything. There are too many choices, and that can grow paralyzing. It’s important to set some ground rules as quickly as possible, to give the thing some shape. You can always abandon them if they don’t work later.

I am normally a skeptic and debunker. That’s usually how I come at things; Darcy comes from that place as well. So a ground rule we established very early on for this piece was that, when dealing with a conspiracy theory we don’t believe—for example, that FEMA is going to lock up all gun owners in concentration camps when the New World Order comes—we would suspend our usual skeptic impulses and try to present that theory the way someone who believed it would.

Lynn Nottage once told me that when you suspend judgment, more interesting questions arise. She’s totally right, and that was totally right in this case, too. So often the conversation around a conspiracy theory both starts and stops with, “Is the person saying this ridiculous?” Before we even get to whether it’s true or not, we’re off to, “Can this person be mocked?” It’s more interesting to ask: Why does this person believe this? How is this argument constructed? What images and ideas are in this theory? What is it its substance?

What are some of your favorite conspiracy theories?

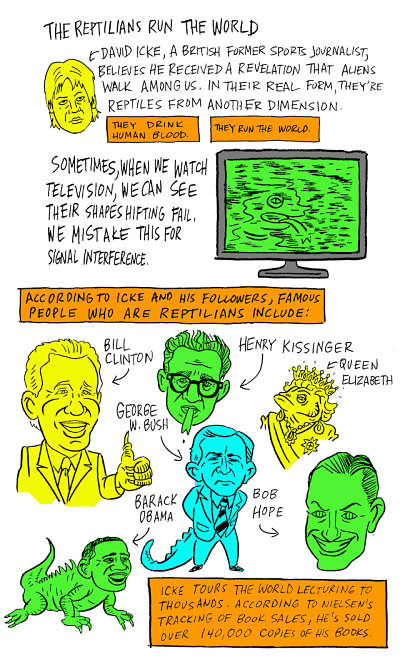

I talked about a few of them in comic form here. One I didn’t get to talk about that I love, though, is the idea that the CIA is responsible for our disdain for conspiracy theories. Here’s the evidence we have: Prior to the 1960s, the term “conspiracy theory” (and conspiracy theorist) was used rarely and, in general, as a value-neutral term. Then, starting in the late 1960s, it changed to a disdainful term. We also have a declassified memo by the CIA from the time encouraging station chiefs and other staff members to call up pliant press contacts and talk about how people questioning the Warren Commission are crazy conspiracy theorists. There’s no way to prove a causal relationship there, of course, but you have to love the idea that the term “conspiracy theory,” along with our attitudes about the term, are the result of a nefarious government plot.

I’m also kind of obsessed by conspiracy theories that are themselves the result of conspiracies. For example, all that Holy Blood, Holy Grail/Knights Templar/Da Vinci code b.s. isn’t true, but it’s the result of a group of people getting together and deciding to forge and then hype historical evidence. The Protocols of the Elders of Zion wasn’t really intended to fuel hatred of Jews; the point of it was to convince one particular anti-Semite, Czar Nicholas II, that liberal governmental reforms were a Jewish plot. The composition of it, and its subsequent planting and “discovery,” was a conspiracy. The conspiracy it details is to some extent less interesting that how and why it was written.

What’s the most surprising thing you learned in your research/development of the show?

Honestly, I’m not really surprised that people believe zany things about extra-dimensional reptilian shape shifters. I’m way more surprised by and interested in things our government actually has done or has thought about doing. One that made its way into the show is Operation Northwoods. After the Bay of Pigs, the Joint Chiefs of Staff were tasked with coming up with a way to gin up a legal method of going to war with Cuba. What they came up with—and it should be said, the operation never happened, but it was proposed and the chairman of the joint chiefs signed off on it—was this thing called Operation Northwoods.

Northwoods involved all sorts of bizarre—I mean, I guess for the most part you could call them “pranks,” if they weren’t potentially deadly—to create a casus belli for war. Among the plans were getting Cuban exiles in the U.S. to commit false-flag terror attacks that could be blamed on Castro; painting Air Force planes to look like Cuban MiGs and flying by passenger aircraft; blowing up a military vessel and blaming it on Cuba; creating faked disturbances at Guantanamo Bay, etc. One of the plans—a very complicated one involving a fake passenger plane that’s empty and destroyed but made to look like it was full—later became a source of inspiration for 9/11 Truthers.

Apart from Protocols, is there a unified field theory of conspiracy theories—one ring that unites them all?

I actually don’t really use The Protocols of the Elders of Zion in the show, despite being obsessed with it. Because of the aforementioned deadpan POV of the piece itself, I thought indulging in something that openly racist would derail the piece. That said, there’s a small snippet of text from Protocols that appears in one place.

A few people have posited Grand Unified Conspiracies. Here’s a good one that involves both the Illuminati and ancient aliens! Our show proposes a few—one involving masons, one involving aliens, etc.—without ever committing to one. Every single theory we examine in the show is pulled from a real-life conspiracy theory, and nearly every image and piece of text in the show comes from research. We’re very strict about not making anything up.

So is this piece a narrative, do we follow specific characters, or is it more abstract than that? Is it going to sound like an opera? Give me a non-spoiler-y feel for what kind of thing we’ll be seeing/hearing.

Let me answer this in a way that’s sure to sell tickets: Real Enemies is a series of interconnected essays about the last hundred years of American paranoia in the form of a multimedia jazz concert.

Seriously, though, Real Enemies has many narratives in it—conspiracy theories are just narratives, after all—and it has an overarching journey that we are taking the audience on. But it does not have a story in the conventional sense. It’s a work of nonfiction, actually, even though it is made out of live jazz music and multichannel video and has a minimum of text that the audience sees or hears. Another way to think of it is as a three-dimensional performed collage.

Honestly, it can be hard to describe because we’re trying to do something new here, something that brings together a bunch of different traditions in a way that pushes the possibilities of live, staged nonfiction storytelling forward. There’s a bit of the techniques of the graphic novel in there, a bit of documentary film, a bit of the essay, a bit of found text poetry. It’s many different forms, all happening at once. I find this thrilling, personally. I’m drawn to theatre in part because it’s the most complete of art forms: You’re always combining fashion (costumes), poetry (text), sculpture (set), dance (blocking), etc., when you put on a play. We’re taking that same idea and throwing some other forms into the pot.

What are some influences/reference points/prompts for Real Enemies—or, put another way, what’s the conspiracy theory that would explain how your show came to be?

So our shadowy cabal for this show is myself (writer and director), Darcy James Argue (composer) and Peter Nigrini (projection designer). Darcy and I first worked together on Brooklyn Babylon at BAM, which I helped shepherd but did not co-create. When BAM contacted him a couple of years later to ask if he might be interested in pitching a follow-up, he and I started brainstorming a bunch of ideas. We were interested for a while in doing something about John Brown and the Harper’s Ferry raid. Then we were interested in Aum Shinrikyo and the Tokyo Sarin Gas Attack (which ended up in Real Enemies). Neither of those felt right.

Then, Lindsay Beyerstein, who is an investigative journalist and Darcy’s girlfriend (and the person through whom we met), was reading this cultural history of American conspiracy theories called Real Enemies by Kathryn Olmsted. Lindsay gave it to him because she thought it might make for an interesting show. He devoured it and loved it and gave it to me to read. I really responded to it, but at that point had no idea how we would make a multimedia jazz piece with a minimum of text out of a century of American paranoia.

With Kathryn Olmsted’s permission, we stole Real Enemies’ title and began trying to figure out what stories we wanted to tell, what questions we wanted to ask, and how. Soon, Peter Nigrini signed on as a co-creator as well, in charge of the video component. He had this idea that the projections should be on a broken-up series of surfaces, so that the audience was always making connections between images, the way conspiracy theorists do. Darcy also really wanted to explore the history and methods of 12-tone composition—which was, and remains, a heavily politicized form of music whose prominence people blamed on a shadowy cabal—and figure out how to realize his own version of 12-tone serialism’s rules in Big Band jazz.

This led us to the organizing principle (and major visual element) of a clock. Clocks are really important to conspiracists. Time, as Richard Hofstadter puts it, is always just running out to paranoids. And, of course, there’s the Doomsday Clock. And clocks are an important motif in Alan Moore’s Watchmen, which is probably one of the great paranoid apocalyptic works of the 20th century.

I spent about 18 months researching and writing the show. Researching involved everything from historical texts to declassified documents to cheap documentaries put together by conspiracy theorists and thrown onto YouTube. In terms of actual influences on the show, I know that I’m very influenced by Laurie Anderson’s multimedia pieces and by Simon McBurney as a director (particularly, for this one, The Elephant Vanishes). In terms of film, the three paranoid films of John Frankenheimer (Seven Days in May, Seconds, and The Manchurian Candidate) and Alan J. Pakula (All The President’s Men, Klute, The Parallax View). The films of Errol Morris. Orson Welles’ F For Fake. Don DeLillo’s Libra. Maruti Evans, who designed the sets and lights, and I talk about the cinematography of Gordon Willis all the time.

Darcy’s music pulls from a lot of places, everything from the film scores of Michael Small (who did Klute and Parallax) and David Shire (The Conversation and The Taking of Pelham 1-2-3, which is a 12-tone score), Hanns Eisler, post-minimalist American classical music, Nicaraguan són, early ’80s electro-funk hip-hop—somehow it’s all in there. I don’t know how he does it, honestly.

Do you think we’re living in a more conspiracy-minded age than ever, or do you see this kind of thinking surfacing throughout history?

Everyone always thinks that they are in a time of heightened conspiracism. But there’s actually a really great book writing up a series of recent studies called American Conspiracy Theories that makes it clear that the actual level of conspiracism in America is fairly stable, with two notable exceptions: The Second Red Scare in the 1950s and the banking crises of the 1890s. The nature of those conspiracy theories, and how frequently and prominently they’re discussed, shifts all the time, but the actual level of conspiracy theorizing is fairly constant. We are always in the age of conspiracies. Nearly every American believes at least a conspiracy theory, and a conspiracy theory that George III was fomenting slave and Indian rebellions as part of a plot to turn the colonies into a totalitarian state is the basis on which our country declared independence.

Conspiracy theory lightning round:

1. Warren report, fact or fiction?

Fact. What’s most interesting about the JFK Assassination is not the assassination itself but how counter-theories about assassination emerged,

2. 9/11—inside job?

No. I think our intelligence services and the administration in place at the time were incompetent and failed to stop a preventable attack (that I lived through, having moved to New York just a few months earlier). I think for some people it’s scarier to imagine the people in charge of the wealthiest, most powerful nation in the history of the world with the most technologically advanced and deadly weapons the world has ever seen are buffoons, and thus they imagine them to be, essentially, Voldemort.

3. The crack epidemic: CIA plot?

I believe that what Gary Webb documents in his book Dark Alliance is true: that after Congress cut off money for the Contras, the CIA was doing whatever it took to make sure they got their funding, and this included turning a blind eye to, and at times actively aiding, Contra cocaine smuggling into the United States. Webb never argued—and I do not believe—that the CIA invented crack cocaine and specifically unleashed it into poor African-American communities. But the CIA still bears responsibility for the outbreak of crack, because the sheer volume of cocaine they helped import into the United States caused the price of wholesale cocaine to drop to such a point that crack became inevitable.

4. The official Abbottabad story: half-bullshit, all bullshit, somewhere else on the spectrum?

I just loved Jonathan Mahler’s re-reporting on this story, because it’s about the same thing our show is about, to some extent: uncertainty. We don’t even really know what happened with the Bay of Pigs. We will never know what really happened in Abbottabad. I don’t believe the Zero Dark Thirty story for a second, but I’m also not sure Seymour Hersh’s version is totally accurate. The real issue is this: If all of our national security reporting is simply based on what people within the national security establishment tell reporters, how are we ever going to know what’s really going on?

5. The Gunpowder Plot: Did Rome give the green light?

I mean… would you put it past them?