Two entirely different theatrical points of view come across in Razzle Dazzle, a well-reported account by New York Post columnist Michael Riedel of Broadway’s late-20th-century transformation into an efficient moneymaking machine, and Joy Ride, a serious-minded collection culled from John Lahr’s 21-year stint as the New Yorker’s drama critic. Riedel looks at theatre as a business, fueled by big-budget musicals and financed by shrewd impresarios like the Shuberts, Jimmy Nederlander, and David Merrick. Lahr considers theatre as an art, forged by a writer’s vision; playwright profiles occupy more than half of his pages, and Lahr is unrivaled at tracing the way the personal experiences of Arthur Miller or Tony Kushner translate into words that capture our spiritual, social, political, and cultural states.

About the only thing Riedel and Lahr have in common is that neither cares for Stephen Sondheim’s work. His dark, audience-challenging musicals are simply irrelevant to Razzle Dazzle; they’re cited only in passing as examples of the kinds of shows that don’t make money. By contrast, blockbusters like Les Misérables and Cats, which ushered in “the era of the global Broadway spectacle,” get lengthy production histories as well as savvy assessments of their impact on the business of Broadway.

Meanwhile, Lahr’s shopworn carping that Sondheim shows are cold and abstract is interesting only as a symptom of his general ambivalence about the Rodgers and Hammerstein revolution that killed off the brand of amusing, ephemeral musicals that were once headlined by comedians like his father, Bert Lahr. Oklahoma!, John Lahr writes, replaced “anarchic, freewheeling frivolity that traded in joy” with what he bafflingly terms “the musical…of interchangeable parts.” The reviews reprinted in Joy Ride acknowledge a few musicals that display the ambitions Lahr readily grants to drama—including Kushner and Jeanine Tesori’s Caroline, or Change, and, to be fair, Sondheim and Hugh Wheeler’s Sweeney Todd—but he apparently prefers musicals that know their place as clever fluff, like The Producers. Its director, Susan Stroman, is one of only four directors profiled here, keeping startling company with Nicholas Hytner, Ingmar Bergman, and Mike Nichols.

Strong opinions are, after all, the critic’s stock-in-trade, and it’s stimulating to occasionally disagree with judgments handed down by someone as committed to and knowledgeable about the theatre as Lahr. Joy Ride showcases his generous spirit: There are no bad reviews (the few mixed ones are—surprise!—of musicals), and naturally only playwrights or directors whose achievements he admires get the New Yorker’s luxurious profile treatment, which requires three to four months of hanging around with the subject to eventually produce 6,000–10,000 words that are invariably appreciative, although also studded with some fairly intimate revelations about (for example) David Mamet’s emotionally abusive parents and Neil LaBute’s wife, a devout Mormon “conspicuously absent” from the audience at his scabrous, sexually explicit plays. Not everyone, Lahr admits in his engaging introduction, wants to participate in what he terms “a collaboration.” “I love what you do, John,” Mel Brooks told him. “I just don’t want you doing it to me.”

There are two schools of theatre criticism. One positions it as a consumer service: The critic, a stand-in for the average audience member, basically tells people whether or not a show is worth seeing and maintains a careful distance from theatre professionals to avoid conflict of interest. The other takes a broader approach, aiming to give a sense of the artists’ aims, what they have to say, and their connection to both contemporary life and theatrical history. Critics that anyone would bother rereading belong to the second school, and they usually work in the theatre, as well, Kenneth Tynan and Harold Clurman being prominent examples. Lahr follows in those footsteps; he was literary adviser of the Repertory Theatre of Lincoln Center from 1969 to ’71, and Elaine Stritch at Liberty, whose text he coauthored, received a Tony in 2002. His personal acquaintance with writing a script and putting it into rehearsal gives his profiles a pleasing depth, and he’s a good reporter, too; apt quotes from interviews with relatives and colleagues add to our understanding of August Wilson and David Rabe, among others.

Lahr occasionally flaunts his insider status with stories of being shooed out of the Lincoln Center lobby because he and Sam Shepard looked too scruffy, or having Wallace Shawn show up on his doorstep in the early ’70s with six scripts in hand. But usually, as in his excellent profile of Nichols, he nicely balances rapport with his subject and a detached career evaluation that isn’t necessarily wholly positive. Although its contents overlap with Lahr’s two previous New Yorker collections (Honky Tonk Parade and Show and Tell), this volume provides a fine summing-up of what Lahr calls “the happiest years of my writing life.” His full-length biographies, most recently the award-winning Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh, constitute Lahr’s lasting achievements, but it’s obvious here that his work as a journalist was indeed a Joy Ride.

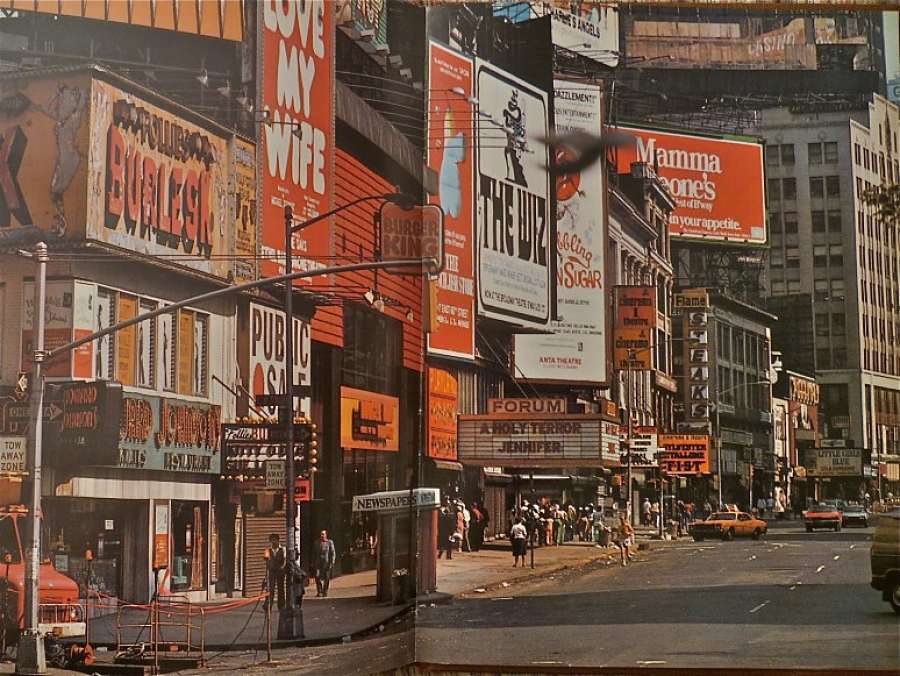

Riedel offers pleasures of a different nature in Razzle Dazzle, which opens with a 1963 ticket scalping scandal and gleefully delves into other mostly legal but definitely cutthroat business practices as it chronicles Broadway’s near-demise in the 1970s and the subsequent struggle to revitalize it as the center of the commercial theatre industry. (Nobody in this book talks about art.) The self-appointed leaders of this battle were Gerald Schoenfeld and Bernard B. Jacobs, who in 1972 engineered a coup against the alcoholic great-nephew of the Shubert Organization’s legendary founders to assume control of the organization as Broadway faced its worst crisis since the Depression. Attendance plunged 50 percent between 1968 and 1972: At one point in the ’71–’72 season only 5 of the 17 Shubert theatres were open.

“We are fighting for the survival of the American legitimate theatre,” Jacobs proclaimed, and Riedel pretty much takes him at his word, praising the Shuberts (as Jacobs and Schoenfeld were collectively known) for not raising much-needed cash by selling their not-yet-landmarked theatres but instead doubling down by investing in productions like Pippin and such attention-getting events as Liza Minnelli’s 1974 concert at the Winter Garden. At the same time, he acknowledges the criticisms of non-theatre-owning producers, who complained that the Shuberts negotiated sweetheart deals with the city’s powerful theatrical unions that contributed to soaring production costs, which became even more prohibitive after the Shuberts rewrote theatre rental contracts to take a smaller percentage of box-office receipts but bill every house expense, “even toilet paper,” to the show in residence.

Business reporting like this, based on firsthand interviews, makes up the freshest portions of Razzle Dazzle. But for readers who don’t care why it was so important to Cameron Mackintosh to get a percentage of the “flow” (interest on advance ticket sales) for Cats, Riedel provides plenty of more familiar but undeniably enjoyable anecdotes about the creation of megahits like A Chorus Line, Annie, and La Cage aux Folles, as well as good dish about such flamboyant characters as Michael Bennett and Tommy Tune. He also paints a vivid portrait of the bitter rivalry between the Shuberts and the Nederlander theatre chain, which culminated when Nederlander-backed Nine beat out Shubert-financed Dreamgirls for the 1982 Best Musical Tony and Schoenfeld was poor sport enough to demand a recount. (He didn’t get one.)

By the time Jacobs died in 1996, which is essentially when Razzle Dazzle ends, Broadway’s survival was no longer in doubt. Its theatres were landmarked, after the uproar that greeted the Shubert-supported demolition of three historic (non-Shubert) houses to build the Marriott Marquis Hotel. Disney had a family-friendly beachhead at the Palace with Beauty and the Beast, to be joined in 1997 by The Lion King in the spectacularly renovated New Amsterdam Theatre, which completed the clean-up of Times Square so long sought by the Shuberts.

Revenues were at an all-time high, goosed by ticket prices that had been rocketing upwards since Jacobs pushed for a $15 top when Richard Burton joined Equus in 1976. Steadily rising attendance figures suggested he was right to insist, “If the public wants the show, they’ll pay for it.” That this public was increasingly composed of tourists and businesspeople entertaining on expense accounts did not concern the Shuberts, nor is it an issue Riedel addresses. He accepts the values of a world in which an annual box-office gross exceeding $1 billion must mean the theatre is healthy. It’s not necessary to share those values, though, to find Razzle Dazzle smart, well-informed, and informative about an important chapter in commercial theatre history.