Theatre is ephemeral but the Internet is forever (so far, touch virtual wood). So we who do theatre journalism have some kind of special duty, not to mention a unique opportunity, it seems, to be the guardians of record for the shows and people who pass across our stages and then are gone.

But print space is at a premium, even online. I know from my reviewing days that word counts for most theatre reviews have plummeted across the board—that is, in the places that still print them at all. In New York, the supposed U.S. capital of both publishing and theatre, theatre reviews have either been eliminated altogether in some quarters (Backstage) or noticeably downsized (Newsday, the Post, Time Out New York, Village Voice).

It’s in that context of reduced space that a decision by the New York Times to eliminate end-of-review credit listings from both their print and online editions—listings in which all the principal designers and stage managers, in addition to playwright, director, and cast, were dutifully recorded for posterity—has provoked concern from a group of playwrights, led by Annie Baker, who have formally requested that the Times reinstate those listings. Baker, the critics’ darling who most recently gave us the brilliant John and whose Pulitzer-winning The Flick is still running (and whose recent appearance on Marc Maron’s WTF podcast is a must-listen), reactivated a dormant Facebook account to bring attention to this policy change.

In a private but widely shared post, Baker wrote, “I have always felt that the designers are the co-authors of my shows, and just as important as the playwright and director and actors. Getting to work with brilliant designers has been the great unexpected joy of my career, and these people already don’t get enough credit in a culture that undervalues composition and color and light and material and SPACE, for Pete’s sake, the very things that make our medium magical.”

Though I can’t pinpoint the exact year the Times began this policy (I found end-of-review credit listings for plays up through 2011, but as early as 2012, I found reviews without them), I’ve been informed that this decision has also affected film reviews, so theatre hasn’t been specially singled out for punishment. (I’ve been waiting on word from the Times about this policy and will print their response when I get it.) It might be pointed out, though, that while film credits are amply represented online, theatre credits can be harder to track down; Variety still does listings at the end of its reviews, and for Broadway shows there is of course the Internet Broadway Database, but let’s not pretend that’s representative of even New York theatre (Baker, for one, has never been staged there), let alone the American theatre. As Baker points out in a letter she and a large group of co-signers sent to the Times’s editors last week, the archive value of that information is hard to overstate. The full text of her letter, and the list of co-signers, is below:

Subject: a letter from 80 playwrights

Dear Scott Heller and The New York Times,

We are reaching out because we’d like to talk to you about the recent elimination of the full credit box in your theater listings and reviews.

We playwrights are always mentioned in the listings and reviews. This is not about us. We think the stage managers and sound and lighting and set and costume designers we work with are just as important as we are when it comes to making theater.

These people are so often overlooked, even though our medium is, literally, coordinating moving bodies, in clothing, with accompanying sound, through light and architectural space. The credits at the end of the reviews and listings are often the only way designers and stage managers are recognized at all. And these people are real artists. They’re not helpers. They’re our collaborators. They’re the show itself.

It’s also important for your readers to be able to find out days, months, years later, who created the shows they saw and read about. There are so many theater artists who aren’t writers and directors and actors whose careers should be followed and documented, regardless of the writers and directors and actors they’re working with, simply because they make extraordinary work.

We need talented artists in New York City to continue to want to pursue these fields. And if they’re unnamed and uncredited in the Times it’s bad for all of us. Their names are as important to the future of American theater as the names below.

Please restore the original credit box to your reviews and listings, online and in print.

Sincerely,

David Adjmi

Annie Baker

Stephen Belber

Eliza Bent

Hannah Bos

Adam Bock

Sheila Callaghan

Mia Chung

Erin Courtney

Lisa D’Amour

Eisa Davis

Kristoffer Diaz

Steven Dietz

Bathsheba Doran

Jackie Sibblies Drury

Erik Ehn

Will Eno

Halley Feiffer

Melissa James Gibson

Daniel Goldfarb

John Guare

Rinne Groff

Stephen Adly Guirgis

Jordan Harrison

Amy Herzog

Lucas Hnath

Tina Howe

Quiara Hudes

Sam Hunter

David Henry Hwang

Naomi Iizuka

Branden Jacobs-Jenkins

Len Jenkin

Jeffrey Jones

Rajiv Joseph

Stephen Karam

Sibyl Kempson

Arthur Kopit

Kristen Kosmas

Tony Kushner

Deborah Laufer

Young Jean Lee

Dan LeFranc

Tracy Letts

Kenneth Lonergan

Matthew Lopez

Kirk Lynn

Taylor Mac

Duncan MacMillan

Laura Marks

Tarell McCraney

Terrence McNally

Charles Mee

Carly Mensch

Itamar Moses

Gregory Moss

Carlos Murillo

Janine Nabers

Qui Nguyen

Bruce Norris

Lynn Nottage

Sylvan Oswald

Jiehae Park

Max Posner

Adam Rapp

JT Rogers

Sarah Ruhl

Kristina Satter

Heidi Schreck

Wallace Shawn

Cori Thomas

Paul Thureen

Kathleen Tolan

Sarah Treem

Francine Volpe

Anne Washburn

Gary Winter

Doug Wright

Stefanie Zadravec

Anna Ziegler

(United Scenic Artists has also drafted a protest letter.)

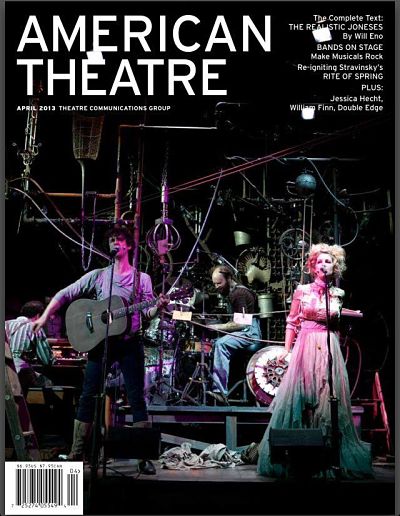

While I look forward to whatever Annie Baker writes next, and probably need not worry that it will be produced on a stage near me, countless other shows I hear about, read about, even report about are harder to catch (theatre’s ephemerality again, not to mention its locality). It gave me great satisfaction, then, to finally witness Futurity, in a Soho Rep/Ars Nova production at the Connelly Theatre (through Nov. 22), in what feels like a triumphant realization of a new-model American musical. I first heard about this sui generis work of theatrical/musical/moral imagination in 2012, when freelancer Michael Criscuolo wrote about its American Repertory Theater production for our magazine; a year later, the show, written by the N.Y.-based indie folk/rock band The Lisps, ended up as our cover image for a story I wrote about a trend I’d had my eye on for a while: band-driven musicals.

While I look forward to whatever Annie Baker writes next, and probably need not worry that it will be produced on a stage near me, countless other shows I hear about, read about, even report about are harder to catch (theatre’s ephemerality again, not to mention its locality). It gave me great satisfaction, then, to finally witness Futurity, in a Soho Rep/Ars Nova production at the Connelly Theatre (through Nov. 22), in what feels like a triumphant realization of a new-model American musical. I first heard about this sui generis work of theatrical/musical/moral imagination in 2012, when freelancer Michael Criscuolo wrote about its American Repertory Theater production for our magazine; a year later, the show, written by the N.Y.-based indie folk/rock band The Lisps, ended up as our cover image for a story I wrote about a trend I’d had my eye on for a while: band-driven musicals.

Put briefly, I’d noticed that increasingly the American musical was finding its freshest sounds and forms in shows created by and with bands and singer/songwriters, and that most of these shows featured said creators as onstage players (at least in their original incarnations). From Stew to Groovelily, from Dave Malloy to Sky-Pony, from PigPen Theatre Co. to Anais Mitchell, something seemed to be brewing, and as a sometime singer/songwriter and BMI musical-maker myself, I was eager to dive deep on the subject. I remember fondly a long winter day in 2013 I spent at various Brooklyn eateries having free-ranging chats with Stew and Heidi Rodewald; with Dave Malloy, who had a hefty accordion case in tow, as he was en route to a workshop; and with The Lisps’ dapper frontman, César Alvarez, who laid out a vision of a thousand DIY musicals blooming that I found intriguing:

Whenever we have a gig and we say, “You know, we wrote a musical,” and then we play a couple songs from it, so often bands come up to us afterwards and say, “We wrote a musical, too! We just don’t know how to do it,” or, “We have this idea for a musical, we just don’t know how to write it.” Everyone wants to write a concept album, and then everyone wants to put it onstage. Everybody’s concept album could work as a musical. I think it would be really cool to see more support for that type of creativity.

Of course, that’s what places like Ars Nova, ART’s Oberon space, and the Public Theater’s Joe’s Pub, among others, have been doing for years; Ars Nova even helped incubate a certain hip-hop improv troupe you may have heard a bit about.

A few more words about Futurity: Alvarez spoke recently to our own Allison Considine about the show’s personal inspiration, the horrifying Greensboro massacre of 1979, in which close friends of his parents were among demonstrators attacked by members of the KKK and the American Nazi Party; there were five fatalities, two of whom Alvarez is named for. This harrowing backdrop isn’t a prerequisite to grasping Futurity, by any means, though it explains some of its urgency, and its curious sense of legacy. Certainly, this is a forward-looking, form-bending show, at least in musical-theatre terms, but as it moves the format forward it also harkens back to other, older traditions—to campfire singalongs, folk-song rounds, military cadences.

And while I’m not sure every bit of the show’s strange mashup of Civil War Americana and retro science fiction “works,” either in traditional musical theatre terms or on its own terms, the entire living, breathing contraption on the Connelly stage is so engaging, and has such internal integrity and intensity, that I found myself utterly captivated, even moved. Somehow, while director Sarah Benson and her designers have worked their seamless, lapidarian magic with the staging (clearly this is the same director who gave us the wittily multilayered mounting of Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’s An Octoroon), Futurity palpably retains the feeling of homemade, almost outsider art, from Eric Farber’s Rube-Goldberg-meets-Harry-Partch percussion machine to the deadpan banter of Lisps leaders Alvarez and Sammy Tunis.

This would all be mere stylistic diddling if it weren’t for the questing moral hunger, and authentic sense of drama, that animate Alvarez’s often dense yet startlingly direct songs, from which the show was born (and/or a bit vice versa). In songs like “Singularity,” “Every Egg Broke,” and “Thinking,” among others, Alvarez displays a courage to both embrace big-picture idealism and engage in a smart, anguished self-critique of it that put me in mind, oddly enough, of Tony Kushner (or Lisa Kron, who joined Alvarez and me for a talkback after last Saturday’s performance). And this is where the stark Civil War setting is no mere game of historical dress-up, or a case of borrowed significance. Instead it registers as the sharpest imaginable counterweight to the lofty notion that we could ever achieve both peace and justice, as well as a challenge to the fervent hope that collective human effort—represented here variously by a violent struggle against injustice, by an increasing reliance on ever more sentient technology, even by the act of making music and theatre together—can save us from ourselves.

There might more mundane applications for a collective hivemind, of course. In “Singularity,” Alvarez imagines a giant data stream in which

Every piece of food you taste and every thought you cogitate,

Every sound that you can hear and sight you see for years and years,

All stored up so conveniently on peta-bytes of memory,

So you can always reference them in case you forget anything

Surely there will be room in that vast, incipient information cloud to credit every theatre artist for the work they do.