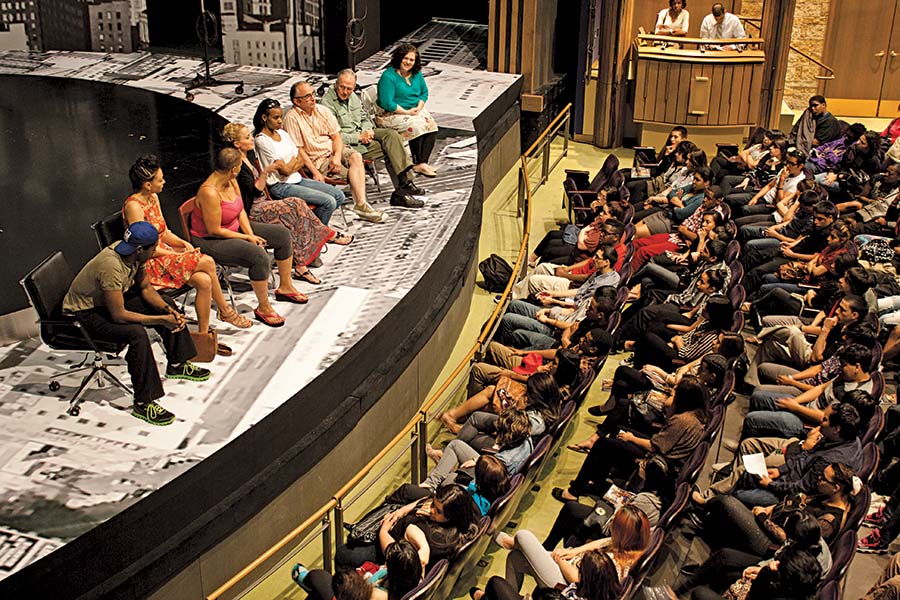

In many ways a theatre can be compared to a community center—both are public places to gather, to socialize, to learn, to be entertained. Now some theatres are intentionally taking up the mantle, fashioning themselves into civic hubs where engagement programs are designed to connect onstage programming with audiences apart from their time in a darkened theatre, and to create initiatives to address specific needs in the community. Though it’s called by many names, engagement work as it’s practiced in today’s theatres encompasses everything from pre- and post-show talkbacks to student matinees, from lobby displays to special workshops. It can also include ongoing programs at other partner organizations. Essentially, it’s all the work that happens outside of a theatre’s ticketed events. And while some theatres have been doing this work for a long time, and others have put engagement at core of their identity from the start (Cornerstone Theater Company, Ten Thousand Things, Sojourn Theatre), in the past few years more theatres than ever have been expanding their mission statements to include engagement and to strengthen their connections with audiences beyond the subscription season.

“I think organizations are starting to recognize the responsibility they have to do something more than just inviting people into their space—that is not enough anymore,” said Willa Taylor, the director of education and engagement at Chicago’s Goodman Theatre. The Goodman’s 30-year-old engagement and education program is one of the oldest in the country. But when Taylor started there 10 years ago, the Goodman had just three engagement and education programs; she has upped that number to 13. Taylor previously worked in education and engagement at D.C.’s Arena Stage, and at Lincoln Center Theater in New York City. Looking back at her decades-long career, she can pinpoint when theatres began to offer more opportunities to teach students and audiences: the first major arts education cuts in schools in the 1970s. Arts funding also saw cuts in the subsequent, and the need for both engagement and education has only increased since then.

But how are these two “e” words different or similar?

“We believe that education and engagement are in some ways synonymous,” said Taylor, adding, “The difference that we make as an institution is that we think of it in terms of who we are serving.”

Programs with students and teaching artists fall within the Goodman’s education program. But the learning extends to adults, with audience engagement programs and initiatives in various neighborhoods in the Windy City. Indeed, the Goodman’s engagement and education department title doesn’t include the word “community.” After all, there is not just one community in Chicago, but many pockets of varying groups impacted by the Goodman’s programs.

For many theatres, education and engagement programs work in tandem both to build audiences for particular shows and to identify specific needs in the community. At Center Theatre Group in Los Angeles, this work is led by Leslie K. Johnson, whose title is director of social strategy, innovation, and impact. (CTG also has a director of education and engagement, Tyrone Davis.) At D.C.’s Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company, the engagement work is headed by Kristen Jackson, director of connectivity. Marcie Bramucci is the director of community investment at People’s Light in Malvern, Pa.

As you may have noticed, there is no consensus in this field on job titles, just as there is none on terminology, process, or measurement. For each theatre, “community,” “audience,” and the act of “engaging” are vastly different things. At American Repertory Theater in Cambridge, Mass., the two-person education and engagement department is also under the umbrella of the theatre’s marketing department, and leads accessibility initiatives. Center Theatre Group’s education and community partnerships department is made up of folks focused on education, others on partnerships, and others on community initiatives.

However many ways this work is weaved into an organization, the end goals are the same: to welcome underrepresented audiences into the theatre, create meaningful experiences, and build the theatre’s presence outside of its brick-and-mortar spaces.

“I describe my job as connectivity director as looking to deepen the conversation around the shows that we produce and create opportunities for meaningful dialogue and understanding across difference,” said Woolly’s Jackson. “Another important part of my job is to mobilize those communities for whom a play might be particularly relevant, either personally or professionally.”

If the job sounds like a hybrid of community organizing and target marketing, that’s not far off.

Staff focused on engagement work have learned to look at what is onstage at their theatre and ask: So what?

“I like to say that at most theatres, our theatre included, 99 percent of the time, 99 percent of the people are focused on making the art,” said CTG’s Johnson. “That is how most theatres exist, because it is such a herculean task to put up these shows, work with artists, and do all the important work to have high-quality programming. That leaves a very small percentage of people concerned about what happens to the art and what ripples it creates in the world.”

Theatres can help multiply or shape these ripples by carefully forming partnerships with community organizations to help build audiences for particular shows. Together they plan special events, talkbacks, or workshops to help steer the conversation.

“I describe part of the work that I do as civic dramaturgy,” said Jackson. “It is really thinking about who needs to be in the room in order to make a conversation about this play and around this play meaningful. Who completes the story?”

This past season Woolly Mammoth partnered with the organization Capturing Fire to plan an Olympic-style queer poetry slam to complement its production of Botticelli in the Fire, about the struggles of Renaissance painters Sandro Botticelli and Leonardo Da Vinci to conform to the conservative ideals of 15th-century society.

“We had board members and company members and other community partners who all came together and served as judges for slam finals,” Jackson recalled. “It was this beautiful, holistic, and vibrant event that really touched on how the themes and the questions embedded in the play came alive and resonated.”

In November 2017 Goodman Theatre had Iraqi artist Ahmad Abdulrazzaq lead a workshop on Islamic calligraphy in celebration of the world premiere of Rohina Malik’s play Yasmina’s Necklace. And for the world premiere production of Claudia Rankine’s The White Card, which explores issues of race, A.R.T. and ArtsEmerson brought in facilitators to help lead a discussion after every performance. Audience members were put into cross-racial pairs and instructed to ask questions, then report out on what resonated with them.

Work designed around particular shows falls squarely into the category of “audience engagement.” A.R.T’s approach to planning and building supplementary programs is based on a concept borrowed from web developers: the idea that in any given audience, there will be skimmers, swimmers, and divers. Skimmers will float, looking at lobby displays or admiring an art exhibit before the show. Swimmers want to splash around a bit more, taking in artist statements. Divers want a deep immersion into the world of the show and might be interested in engaging in deep conversations and learning more background information.

“Everyone’s preferences and methods of engagement and learning are as unique as their thumbprint,” said Brenna Nicely, A.R.T.’s education and engagement director. “When thinking about engagement, we want to do our best to meet everyone where they are and foster different levels of agency in order to spark audience engagement.”

Identifying affinity groups and inviting in people outside of the normal theatregoing crowd to partake in the experiences is part of the challenge, and the fun. Johnson was so enthused in telling me about how she looks for a show’s “connecting points” that at one point she stopped to say, “I just stood up—I got so excited, I literally stood up from my desk! I’m energized by the idea that we can take almost any piece of art and find a community that wants to be a part of it, a community that can inspired by it, and use it as a source of inspiration to connect with people. That’s our work, that’s our job.”

Many who work in these jobs sit in on season planning meetings and are part of the conversation about building initiatives around the selected shows. D.C.’s Woolly Mammoth is looking into ways the connectivity department can have an increasing role in the selection process—and they’re not stopping there. “Even beyond that, we’re thinking expansively about how our partners can have a role in that process,” Jackson said.

Lest this sound to some like a kind of artistic pandering, consider that these are nonprofits with a public service mandate. As Jackson put it, “One of the primary things that we have to offer are the plays that we produce. If you’re building a relationship with a particular community, and they don’t see themselves reflected at that theatre on a regular basis, then it does become increasingly difficult to maintain that relationship.”

Indeed, these partnerships can be challenging to build and maintain. It’s about more than just offering subsidized tickets; it’s also about finding a common goal between the theatre and a local organization and creating a mutually meaningful experience. Said Jackson, “One of the things that I am trying to continually keep in my brain as a refrain is, how do we have relationships that are not transactional but rather transformative?”

Community partnerships come about as a result of theatres and their representatives being present in the community. For her part Jackson attends birthday celebrations, fundraisers, and film screenings, and even a “hackathon” to better connect with the community.

“You have to be passionate about the work to do it, because it’s not necessarily a 10-to-6 job,” said Jackson. “Sometimes you just show up because you care, and that goes such a long way in relationship-building. My job is to make friends, and it’s about figuring out how to be a good friend to people.”

Building partnerships can be something of a long game, explained Taylor. “I spend a lot of time in communities, just sort of making myself and the resources of the Goodman available,” she said. “I try to show up for organizations, to be there both as a witness to the work that they are doing and to be helpful in any kind of way that I can. It takes a lot of time to build trust in community. I have been here 10 years, and it has taken 10 years for some community organizations to ask things from me other than tickets.”

Added Bramucci at People’s Light, “The whole notion of these partnerships is that we are both changed as a result. How are we growing together? That is incredibly exciting to me in this work, how People’s Light continues to evolve and become more deeply connected.”

When a show closes, that can mark the end of a particular working partnership. The Woolly tries to keep its past community partners connected to the theatre through an “ambassador” program, by which teaching artists at the company offer public speaking and voice and speech workshops to community partners.

But sometimes when a partnership clicks, many theatres form long-standing partnerships with organizations to address a particular need in a community. A.R.T. offers tickets to people with early onset Alzheimers and their caregivers at Goddard House Assisted Living to particular performances, just so that this community can meet each other and socialize.

The Goodman’s NOURISH program, a partnership with the Center for Performance and Civic Practice, trains teaching artists to use art-based problem-solving solutions for community-identified issues. “That is very much about using our artistic assets and habit of mind to develop community activists and artists who are interested in community work to understand how they can use their talents to make change in their communities,” explained Taylor.

Taylor’s most prized program is the GeNarrations program, which partners with nursing homes and personal care facilities throughout the city to teach storytelling skills. The Goodman also works with RefugeeOne, an organization that offers settlement services for refugees in the city of Chicago. The theatre offers sewing workshops for refugees and eventually hopes to be able to create a job placement program for the participants, looking to the Theatrical Workforce Development Program at New York City’s Roundabout Theatre for inspiration.

Similarly, Center Theatre Group invites community members to its costume shop in Boyle Heights, a neighborhood east of downtown L.A. They also offer sewing circles and workshops teaching basic skills. The aim is to help those interested in getting jobs in Boyle Heights, the city’s fashion district, or at CTG’s costume shop.

“If we are making people’s lives better through theatre, I feel that the measure of success is somewhere in there,” said CTG’s Johnson. “Making their lives better doesn’t have to be spiritual or attitudinal—it can also be concrete.”

Another way theatres engage communities is by making them part of the work. People’s Light’s New Play Frontiers program is a long-term initiative that invites playwrights to engage with the people of Chester County, Pa., and to write a new play inspired by the concerns of the region. For the latest installment, playwright Dominique Morisseau interviewed board members and young and old patrons of the Melton community center, a longstanding community partner of the theatre’s. Morisseau’s play Mud Row, about the future of the neighborhood, will bow next spring.

“We’re developing partnerships within our community so that we can be telling the stories that go out of our place and our people,” said Bramucci. “If not us, then who?”

CTG’s Johnson points to the 2015 community performance of Popol Vuh, presented in partnership with El Teatro Campesino in L.A.’s Grand Park, as a successful example of bringing the community onto the stage.

“To see some people who had never done theatre work right alongside veteran artists and mount this enormous, colorful, multidisciplinary story about their community was really meaningful—I feel choked up,” said Johnson.

Others put this work the center of their theatremaking as a matter of course. At Brooklyn’s Irondale Center, a partnership with the New York Police Department called “To Protect, To Serve, and To Understand” brings civilians and police officers together for 10 weeks to have conversations and create a show based on their experience together. And A.R.T. has partnered with Harvard University’s Center for the Environment to develop new works about the growing concerns surrounding the environment.

At bottom community engagement work is really about community investment. It’s not just about going outward, sharing the work a theatre does with the community outside its doors. It is also about turning over the tools, resources, and staff of a theatre to the community it’s part of, whom it belongs to. As Bramucci put it, “We are galvanizing resources, whether they are internal or external, to meet a community need.”

In 2016, People’s Light sent its production team to the Melton community center to build a stage for presidential candidate Hillary Rodham Clinton to speak on. While she didn’t end up delivering her speech there, the project became a platform for local politicians to hold their rallies during campaign season.

One of Woolly Mammoth’s prime assets is its location, so it offers up its space for organizations in need. The Woolly served as a meeting point and place to get water during the 2017 Women’s March in Washington, D.C. This spring, the Woolly opened its doors for the Parkland students to gather before and after the landmark March for Our Lives event. The students shared a dinner onstage, a Woolly tradition. The theatre also shares its space with its community partners, including ONE DC (Organizing Neighborhood Equity), Black Lives Matter DC, and DC Coalition for Theatre and Social Justice.

Johnson pointed to theatre companies offering voter registration in their lobbies as a prime example of theatres providing public good. “The work that we are doing can be entertaining and provide joy and all that good stuff, but to be meaningful in a community, we have to be asking ourselves, in what ways we are providing real public good? Measurable public good with contributions to the sense of community wellness, community life, and civic engagement?” she asked rhetorically. Referring to a program by which CTG offers bilingual performances and readings at library branches around neighborhoods in L.A., she wondered, “Who’s to say that if the only experience someone has with Center Theatre Group is taking the free workshops we’re doing out in one of the local neighborhoods, or going to a play reading that is at their neighborhood library, that those folks aren’t our audience?”

This work isn’t just local; it’s also global. Taylor recalled her mentor and former colleague Zelda Fichandler, who co-founded Arena Stage, as a prime model of engagement. “She was a brilliant thinker, always thinking on a much larger scope and scale than I think the rest of us mere mortals were doing,” said Taylor. “She was always thinking about how to shape the world, not just shape the art in the theatre.”

Passionate leadership and the capacity to connect are necessary traits for this work. Before finding her place in the theatre, Taylor served as a Russian and Arabic linguist in the U.S. Navy. She also oversaw the United Service Organizations’ productions in Greece and managed Armed Forces Radio and Television in Turkey. She attended culinary school and opened a gourmet catering company and bistro.

Her department at the Goodman is made up of worldly employees from varying backgrounds: There are filmmakers, journalists, and anthropology majors. “We all came to this in very different ways,” she said. “Of course we all had a love of theatre, but I think more than anything the part of what we loved about theatre was the potential to change the world and transform people through that art.”

Said CTG’s Johnson: “Many people in our field are highly mission-focused, we want to make a difference in the world. Somewhere between remembering our missions and listening to funders and research and looking at the impact of what we’re doing, and maybe in some ways seeing it diminish over time, we’ve had to ask ourselves: What else? And why? Why do we exist? I think we exist for community engagement.”

A previous version of this story incorrectly listed the location of American Repertory Theater, and mistakenly stated that the company held just one post-performance talkback after The White Card . Both errors have been corrected.