Original published at the Denver Center for the Performing Arts NewsCenter.

Donald R. Seawell had absolutely no fear of dying. He worried about his legacy not one bit. “What’s the point of worrying?” he was fond of saying. “I’ll be gone.”

Seawell died on Sept. 30 at age 103. And ironically, perhaps no one in Colorado history leaves behind a greater cultural legacy than the man who didn’t care about his legacy. Among other things, he left behind the Denver Center for the Performing Arts, today the largest nonprofit theatre organization in America, last year attracting more than 800,000 visitors.

Seawell’s multifaceted career spanned more than seven decades, including producing more than 65 Broadway plays, debating at Oxford Union against Winston Churchill, conducting World War II counterintelligence, publishing the Denver Post, and founding the Denver Center for the Performing Arts in 1974. Even after he stepped down as Chairman and CEO in 2006, Seawell continued to come to work in his emeritus position most every weekday until just a few months before his death.

“The day I retire,” he once said, “is the day they take me out of here in a box.”

Instead, in true Seawell fashion, he was said to be entertaining international guests at his home in the hours before his death.

Wellington Webb, Denver’s mayor from 1991 to 2003, called Seawell “a pioneer with a clear vision and a singular focus on the expansion of the performing arts complex.”

Denver Center Trustee Margot Gilbert Frank called Seawell “a visionary who put Denver on the international map.” Fellow Trustee Judi Wolf, who cared for Seawell in his later years, said Seawell will go down as the most important builder of culture in Colorado history, “hands down.”

Daniel L. Ritchie, the cable magnate and former University of Denver Chancellor who succeeded Seawell as Denver Center Chairman, said Seawell’s esteemed place in theatre history is most secure. “Nobody in the world could have done what he’s done,” Ritchie said.

Governor John Hickenlooper said in a Tweet late Tuesday: “Farewell, Donald Seawell. You were one of a kind. Thank you for all you did for the Denver community. Consider this a standing ovation.”

Seawell has counted among his friends Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Joseph Kennedy, Prince Charles, Noel Coward, and a playbill full of star actors, including Tallulah Bankhead, Alfred Lunt, Lynn Fontanne, and Howard Lindsay. In 2002, Queen Elizabeth II conferred upon Seawell the honorary award of Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire. In 2006, the two-time Tony Award winner was given the Theatre Hall of Fame’s Founder’s Award in New York.

But his singular legacy will be the arts complex he built out of a ghostly part of downtown Denver at a time when absolutely no one other than Seawell was calling for it. “But there was a great need for it, because downtown was dying at that time,” he said.

“There was absolutely no demand for it at the time,” conceded former Denver Center President Lester Ward. “But Don said, ‘Denver will never be a great city unless you have a great performing arts complex.’ And so he saw to it that Denver got one.”

Seawell’s epiphany for creating the arts complex—which now hosts more than 10,500 seats in 10 venues and is home to the Colorado Ballet, Opera Colorado, Colorado Symphony, Broadway tours, and DCPA Theatre Company—came in 1972, when he stopped at the intersection of 14th and Curtis streets. He looked up at the Auditorium Arena, then an aging eyesore from 1908, surrounded by “a mass of urban decay.”

He pulled an envelope from his coat and sketched a blueprint covering four blocks and 12 acres. Before the day was out, he had secured the approval of not only Mayor Bill McNichols but the Bonfils Foundation board, whose primary asset was control of the Denver Post.

Since the 1972 death of longtime Post owner Helen G. Bonfils, his client and producing partner, Seawell has both enjoyed profuse praise for founding the center and weathered lingering resentment over his 1986 closing of the theatre Bonfils built and ran for 40 years on East Colfax Avenue.

“Some people perceived him as a little rough along the edges in terms of getting his way,” Webb said, “but that charge can be made of all of us who are in positions of authority and have a mission to accomplish.”

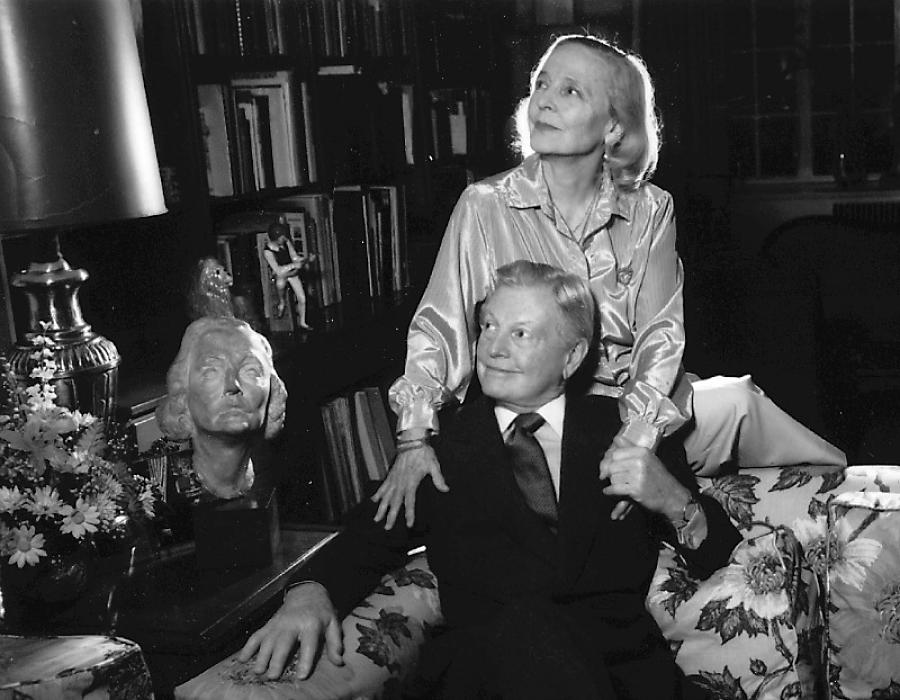

Seawell considered arm-twisting Ritchie into succeeding him as among his top accomplishments. But his greatest, he often said, was being married for 59 years to actress, playwright, and poet Eugenia Rawls.

The honor from Queen Elizabeth was fitting, as Seawell spent a lifetime promoting the cross-pollination of British and American theatre. In 1962, he became the first producer to bring the Royal Shakespeare Company to America. He directed the RSC’s The Hollow Crown on Broadway, and two years later brought King Lear and The Comedy of Errors to New York to mark the 400th birthday of Shakespeare. He was the first American named to the RSC’s board of governors.

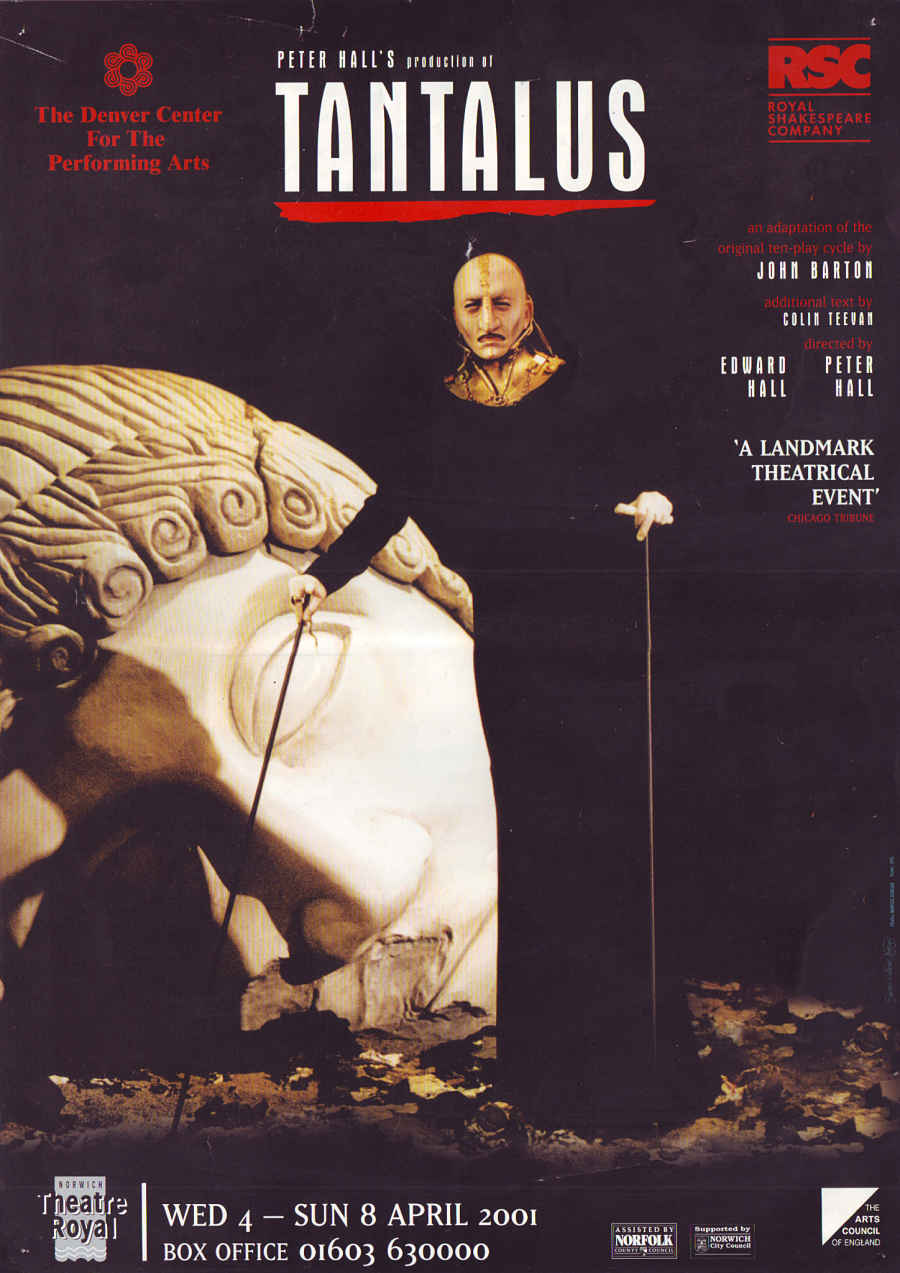

One artistic endeavor ranks above the rest: In 2000, Seawell brought the 10-play Trojan War cycle Tantalus to Denver at a cost of $8 million. The money came from donors and from savings in reducing the number of plays presented by the theatre company that year.

One artistic endeavor ranks above the rest: In 2000, Seawell brought the 10-play Trojan War cycle Tantalus to Denver at a cost of $8 million. The money came from donors and from savings in reducing the number of plays presented by the theatre company that year.

“It was the largest theatre project in the 2,500-year history of the theatre,” Seawell boasted. “Nothing has come along like it, and it probably won’t ever happen again. It brought more attention to the Denver Center than anything else we have ever done. It brought critics from all over the world. It brought people from more than 40 countries.”

The high cost, he said, “was more than repaid in terms of increased donations in the years that followed, as well as national and international recognition.”

The project came about after RSC founder Peter Hall failed to woo European investors for Tantalus. So Seawell came forward offering the services of the Denver Center. “I call him my deus ex machina,” Hall said at the time. “When I had failed to raise the money we needed, Donald came along with that rare mixture of madness and shrewdness which marks all good impresarios and said, ‘I’ll do it.’ He allowed us to dream our dream.”

Seawell was born Aug. 1, 1912, in Jonesboro, N.C., where the young redhead developed an inexplicable lifelong affinity for frogs. He grew up with no religion to speak of because, as he put it, “Organized religion has been a barrier to progress from the word ‘go.'”

He earned his law degree from the University of North Carolina, where in 1932 he saw fellow student Eugenia Rawls walking across the campus.

“I went up to her and said, ‘My name is Don Seawell, and I am going to marry you,’ ” he said. Nine years later, he did.

In a 1936 radio debate, Seawell said of Joseph Kennedy, “It takes a thief to catch a thief.” Kennedy, then head of the new Securities and Exchange Commission, was listening. He called Seawell and hired him upon graduation as an SEC staff member.

On April 5, 1941, Seawell married Rawls, whose Broadway career spanned from 1934 (The Children’s Hour) to 1976 (Sweet Bird of Youth). She died in Denver on Nov. 8, 2000. Over their 59 years together, Rawls wrote dozens of love poems to Seawell, each beginning with the line, “Over the hills of all the world, I would go with you.” They had two children, Brook and Brockman.

With the outbreak of World War II, Seawell was lent to the War Department to work in counterintelligence for Gen. Eisenhower with a combined American and British team working on preparations for the invasion of Normandy.

After the war, he entered private law practice in New York and became increasingly involved in theatre. His career as a Broadway and London producer alongside legendary partner Roger Stevens included milestone productions ofShowboat, Our Town, and Harvey.

“Roger and I once tried to count how many shows we had coproduced, and we came up with 65,” Seawell said. “But that was after a bottle of champagne, so we may have missed a few and doubled some others.”

Seawell began to represent actors and writers including Bankhead, Coward, Ruth Draper and the famous married couple of Lunt and Fontanne, who often referred to Seawell as “the son they never had.” Upon their deaths they left their memorabilia to Seawell, who since has turned it over to the Denver Center.

Seawell also represented Bonfils, a legendary theatre figure and an heiress to the dominant newspaper in Colorado. “Miss Helen” was a tireless philanthropist and theatre champion who partnered with Seawell in producing on Broadway. Back in Denver she built the Bonfils Theatre at East Colfax Avenue and Elizabeth Street in 1953. It was Denver’s crown jewel through Bonfils’ death in June 1972.

Bonfils’ will, and the ownership of the Post, were tied up in a long litigation battle that resulted in Seawell taking control of both. He opened the DCPA in 1974 with money from the Bonfils Foundation, which for years went toward operating The Post and funding Miss Helen’s many cultural philanthropic projects.

Some groused when he built the complex that Seawell was dipping into Bonfils’ money to build what was called a monument to himself. The competing Rocky Mountain News led the fight to have him stopped.

Seawell once admitted the vision for the Denver Center was solely his own.

“Helen wanted very much to have a professional theatre company at the old place, and I got Tyrone Guthrie to agree to come here as artistic director (in the 1960s),” Seawell said. “But he took one look at the old Bonfils Theatre and said it was fit only for Noel Coward drawing-room comedies, and he didn’t do those. So we were going to build another theatre by the old Bonfils, and we actually acquired land for it. But then Tyrone died before we could do anything.”

The creation of the Denver Center required the adherence to the Tax Reform Act of 1969, which represented a significant change in the relationship between government and philanthropy. It established that no private foundation could control any corporation, so Seawell drafted the Bonfils Amendment, which provided that if the private foundation is a satellite of a public foundation, it would not have to give up control. Seawell then created the DCPA as a public foundation and designated the Bonfils Foundation as the satellite to act as a permanent endowment for the DCPA.

The 2,700-seat Boettcher Concert Hall (the nation’s first concert hall in the round) opened first, in 1978. By 1979 the Auditorium Theatre had been renovated. Four new theares made up the Helen G. Bonfils Theatre Complex. The 2,880-seat Buell Theatre opened in 1991, and the Seawell Ballroom followed in 1998.

Seawell was particularly proud to have made the Denver Center home to the National Theatre Conservatory, a three-year MFA program that offered full scholarships to masters students from 1984 through 2012, when it was closed for financial reasons.

Seawell oversaw every aspect of the Denver Center’s growth, and perceptions of him gradually changed from empire maker to unparalleled visionary. His Denver Center Theater Company, now 37 years old, won a Tony Award as the nation’s best in 1998. Today, it’s is nearly impossible to imagine downtown without the Denver Center.

“When I proposed an arts complex, people kept telling me of a study that said in 1974 there weren’t 3,000 people in Colorado who had ever attended a professional theatre production,” Seawell said. “Well, millions of those 3,000 people have attended the theatre now.”

As chairman of the Denver Center’s board of trustees, Seawell’s contract called for him to make just $1 a year, even though he routinely reported to work as many as seven days a week. “But somebody has been forgetting to pay me,” he joked.

Seawell is survived by his children, Brockman Seawell of New York City and Brook Ashley of Santa Barbara, Calif; granddaughter Brett Wilbur of Carmel, Calif., and three great-grandchildren.

John Moore was named one of the 12 most influential theatre critics in the U.S by American Theatre in 2011. He has since taken a position as the Denver Center’s senior arts journalist.