Howie Seago didn’t like Don Nguyen’s play Sound the first time he read it. It explores the controversial issue of cochlear implants through a dispute between a Deaf father and his hearing ex-wife over whether their daughter should get them, but what bothered Seago was the parallel story of Alexander Graham Bell’s quest to invent the first hearing aid to “cure” deafness. He felt the play was too nice to Bell, who’s not exactly a hero in the Deaf community for his views that deaf people should be sterilized and not intermarry. Nguyen took Seago’s concerns to heart and made appropriate changes, and Seago went on to co-direct Sound’s world premiere at Seattle’s ACT Theatre (copresented with Azeotrope) with Desdemona Chiang.

Sound started performances in September, which also happens to be National Deaf Awareness Month. That same month, Deaf West’s Spring Awakening opened on Broadway, raising the profile of Deaf actors in a big way. Off-Broadway, Carol Schneider’s Movements of the Soul, a play about the roots of American Sign Language performed in ASL, English, and French, was workshopped. Meanwhile on television, “America’s Next Top Model”—featuring the show’s first Deaf contestant, Nyle DiMarco—and “Switched at Birth,” with its large percentage of Deaf actors, aired new episodes.

And there’s more on the horizon: New York Deaf Theatre’s fall production is Captive Audience (Nov. 7–22), an evening of short plays by David Ives performed entirely in ASL and accompanied by voice actors. A revival of Mark Medoff’s groundbreaking 1980 drama, Children of a Lesser God, to be directed by Kenny Leon, is aiming for Broadway some time this season, while Nina Raine’s Tribes, another play with a Deaf/hearing romance at its center, has been wildly popular on U.S. stages since its Off-Broadway debut in 2012.

Whether as characters or as theatremakers themselves, Deaf people and their stories have attained high visibility onstage. But the theatricality of Deaf people, their culture, and their language isn’t just aesthetic happenstance; it has been nurtured over decades by visionary leaders, talented performers, and responsive audiences. If Deaf theatre is having a moment, it’s a moment that’s long been in the making.

It was the National Theatre of the Deaf (NTD), established in 1967, that pioneered the theatrical form of blending ASL and spoken word.

“NTD was really the only place where you could have a professional, full-time job in theatre,” says Seago via Skype. “It was a very special kind of a club. We were able to travel all over the world performing. It was quite unique. It’s sad where it’s gone now.” (Today NTD primarily functions as a touring children’s theatre.)

Seago remembers seeing NTD at age 12 or 13, but he never really considered acting as a career until college. He was raised with the oral method, meaning that he wasn’t allowed to sign in school. In college, his roommate asked him to do a play and translated Seago’s lines into ASL.

“Every night I felt like I was a different person signing my lines,” Seago recalls. “The funny thing was, people would come up to me after each show and would sign very quickly, and I would have to tell them, ‘Wait, slow down—I don’t understand you.’ They were shocked that this oral guy who was so awkward in sign language was the same person who was very fluent onstage and looked like he had been signing all his life,” he says. “I liked that feeling.”

Seago paved the way for other Deaf actors to cross over. A breakthrough came when Peter Sellars cast him in his 1986 production of Ajax at the American National Theatre. “I think Ajax really impacted the theatre world and opened hearing directors’ eyes to the possibility of using Deaf actors, and taking advantage and utilizing the uniqueness of sign language in mainstream plays,” he says.

As the first Deaf company member at Oregon Shakespeare Festival (he’s worked there for several seasons, though not the current one), Seago has performed roles initially written for hearing actors. Often in mainstream hearing productions, the roles for Deaf actors are limited to mostly nonspeaking roles, or to characters with less than full mental capacity, Seago says. But OSF artistic director Bill Rauch has cast him in a range of parts, from Bob Ewell in To Kill a Mockingbird to the Duke of Exeter in Henry V. “Deaf people can and should be looked upon as they can do any role onstage,” Seago says.

While Seago hopes that Sound will raise awareness about the range of opinions on cochlear implants, which have created fierce divisions within and around Deaf culture, Tribes also illuminates conflicts between Deaf and hearing people. Russell Harvard originated the role of Billy in the work’s U.S. premiere; Billy is a young deaf man raised in a hearing household with a family who has refused to learn to sign. Harvard, a native Texan, had no clue the show would be such a hit at the Barrow Street Theatre, and would end up keeping him in New York for a year. But he thinks he understands the show’s popularity.

“It’s a universal play,” says Harvard, who also appears in Spring Awakening. “Many people can relate to it. It’s not just centered around deafness. It’s about communication—how to communicate with your kids.” Harvard is hard of hearing but identifies as culturally Deaf—a capitalization that acknowledges a self-identified community as opposed to a medical condition. “My father raised me to be proud of who I am,” he says, “At the time there was no such thing as big D or small D. Later, I found out about the big D and the small D—and I chose the big D.” But proud as he is, he also doesn’t want Deafness to define the roles he gets. “I’m an actor who happens to be Deaf,” he says.

Harvard later played Billy in Tribes at Los Angeles’s Center Theatre Group and La Jolla Playhouse. Raine’s play has been produced in roughly 40 regional theatres so far, and was on the American Theatre Top 10 Most-Produced list in the 2013–14 season. Occasionally, hearing actors have been cast in the role, like at Phoenix Theatre in Indianapolis and Oregon Contemporary Theatre, a decision that always elicits protest.

When Tribes premiered in London’s Royal Court Theatre in 2010, Raine knew Billy had to be cast with a Deaf actor, though some hearing performers did audition.

“It just felt like patronizing the character somehow in doing this Deaf voice that wasn’t their own and they had no knowledge of what it means to be Deaf,” Raine says. “When you start rehearsals, it’s also brilliant to have a Deaf person in the room because the play is about Deafness, so what would be the point of doing a play about Deafness and not having someone in the room who can tell you what it’s like firsthand? It would just be insane, I think.”

Raine was also involved in casting the New York production because it was the North American premiere, but since then, she admits she can hardly keep track of all the productions in the U.S., and sometimes doesn’t even hear about them until they are already happening. It wasn’t until James (Joey) Caverly, who played Billy at SpeakEasy Stage in Boston, Studio Theatre in Washington, D.C., and Berkeley Rep, contacted Raine to tell her that a hearing actor had been cast in one of the U.S. stagings that she was even aware of it.

In response to Caverly’s request that she go on record and say that Billy had to be portrayed by a Deaf actor, Raine decided that when the play is reprinted, she will include a note strongly encouraging theatres to cast a Deaf actor. She also talked to her agent about making the same stipulation when theatre companies get the rights to Tribes. She is hesitant to say that if you can’t find a Deaf actor, you can’t do the play, because as a director, she knows that sometimes things happen, like an actor becoming unavailable at the last minute. Still, she feels, a hearing actor should be a last resort. (Harvard’s understudy Off Broadway was a hearing actor because he also understudied the hearing role of the brother Daniel; that’s the way it’s usually done.)

“What I wouldn’t want is for people to cast some totally ordinary actor and say, ‘Just act Deaf—it can’t be that hard.’ The thing is, if you can’t get a part as a Deaf actor when there’s a Deaf part, when are you going to get cast?”

For the most part, theatre companies have been respectful of the Deaf community’s wishes. Amy Potozkin, casting director at Berkeley Rep, says they only looked at Deaf actors when casting Billy.

“The Deaf community’s feelings were paramount to us every step of the way, beginning with the casting process,” she says. She worked with New York casting director Alaine Alldaffer to reach out to all the theatres that had produced the play, and put out feelers to the Deaf community in the Bay Area and beyond. They ended up casting Caverly.

“Joey is incredibly special and a fantastic actor and charming and attractive and appealing, and deep and funny—and I could go on and on,” Potozkin effuses.

What has also happened is that theatres have been expanding accessibility initiatives as a result of producing Tribes. “We used it as a chance to take a look at accessibility pretty broadly, not just for Deaf and hard-of-hearing audiences, but also for people of limited mobility, for the blind—an across-the-board look and self-evaluation,” says David Muse, artistic director of Studio Theatre and director of its 2014 production of Tribes. For Tribes, at least one performance a week was either sign-interpreted or captioned (people usually have strong preferences one way or the other), mixing when they would fall during the week to provide audience members with options.

Now every production in Studio Theatre’s main series and off-subscription series has sign-interpreted, captioned, and audio-described performances. They also offer on-demand performances if a patron wants one of these performances on a day when one hasn’t been scheduled, and do everything possible to accommodate those requests.

Muse read Tribes even before it came to New York and knew he wanted to produce it. He had to wait for the rights, but he lined up early. “I did the play because I love the play,” he says. One clear side benefit: It also offered a chance to connect with the Deaf community in D.C., the home of Gallaudet University, which is dedicated to Deaf and hard-of-hearing students. Muse reached out to Ethan Sinnott, chair of Gallaudet’s theatre arts department, to inquire about best practices. Sinnott suggested hiring a DASL (pronounced “dazzle”), Director of Artistic Sign Language, a dramaturgical role that involves translating, facilitating communication between deaf and hearing people, and acting as a representative for Deaf culture and Deaf issues. Tyrone Giordano, star of Deaf West’s Big River and Pippin, came on board. Muse says Giordano was instrumental in suggesting things he never would have considered, such as the ideal location for Billy at the dinner table to be able to read everybody’s lips.

Raine thinks that sometimes directors worry about working with Deaf actors for the first time. But Muse says that when done right, it doesn’t feel very different from any other rehearsal process. “It’s human beings communicating with each other and attempting to make a play,” he says. “When it was up and running, what was remarkable to me was how unremarkable it was. By and large, it was a rehearsal room like any rehearsal room I’ve been in, but with somebody following me around and interpreting me.”

Muse hopes to continue to find opportunities to work with Deaf actors, even when the script doesn’t mandate it. “There’s no reason why one necessarily would need to be doing a Deaf-themed play in order to find opportunities for Deaf artists to participate in the work of the company,” he says. That’s what Stan Richardson and Matt Steiner, founders of the theatre troupe the Representatives, discovered in casting Richardson’s play Veritas.

Veritas, about the secret gay witch hunt at Harvard in 1920, had a high-profile Fringe NYC run in 2010. For the Representatives’s production at the Cave @ St. George’s (Oct. 21–Nov. 7), they cast actors of different races, cultures, and ages. “On the most basic level, it’s: Let’s just cast it with the most amazing actors we know already, who might not otherwise get to play these parts,” says Steiner. “It’s also: Let us tell this historical story of these boys being silenced or erased from history with a cast that represents groups that even within our very progressive circles today kind of get sidelined or silenced.”

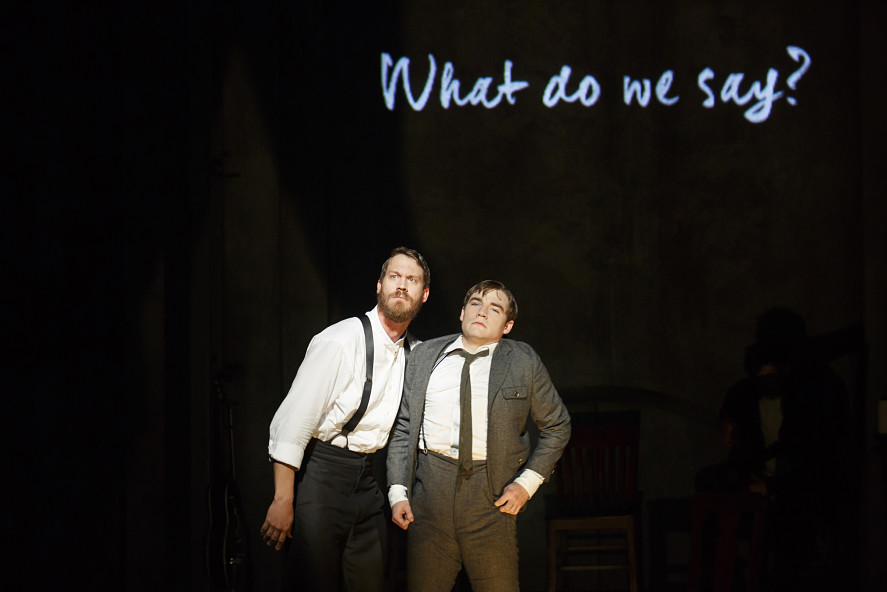

Sticking with that, they cast Deaf actor John McGinty as dental student Eugene Cummings. McGinty starred in Tribes at the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis, Steppenwolf Theatre in Chicago, and Everyman Theatre in Baltimore. Richardson met McGinty when he translated text into ASL for Ramona Clay, a play Richardson wrote for Deaf actor Alexandria Wailes. They thought of him for the role and cast him without an audition. It’s an anachronistic choice, as a Deaf student would not have been admitted to Harvard in 1920, but because ASL was not an acceptable mode of communication at the time, it fits into the world of the play, in which people have to communicate in secret.

Richardson and Steiner carefully considered when characters would sign with Eugene, when they would speak to him, and when words would be displayed via projection. When thinking about projecting his lines, they realized that having writing throughout the play would work well with the idea that the boys’ words were used against them and could also be used to display McGinty’s lines when not spoken. “That’s a great example of something that might have originally been seen as a limitation having this huge aesthetic effect on the entire play,” says Steiner.

This question of how to get two languages across is one that goes into every production in ASL and spoken English. Often, actors will use SimCom, or simultaneous communication, signing and speaking at the same time, which is not realistic. “I very rarely do both at the same time, because you’re not really doing either language justice; the grammatical systems are almost completely opposite,” says interpreter and actor Craig Fogel. “It’s impossible to speak and sign at the same time and get a clear message across. I think sometimes people misunderstand and think that sign language is just English with your hands. People don’t understand that it’s a unique language of its own with its own grammar and syntax.”

In Sound, Seago avoided using SimCom by having actors who weren’t in a given scene voice other actors, integrated into the set so as not to distract. In Spring Awakening, hearing actors voice the Deaf actors, but sometimes hearing actors talk and sign, or sing and sign at the same time.

“What Deaf West does differently is they fight from the start to be as true to ASL as possible,” says Giordano via Google chat, while cradling his infant son in his arms. “They try to find a million ways around all the roadblocks that make this goal achievable. It’s a highly pragmatic process. That can be a fun process for ASL translators, to find that seamless shape/blend that will still remain true to ASL, and it’s exhilarating when it happens.”

Much as the original Spring Awakening made stars out of its cast, this one is sure to be a springboard for Deaf actors Miles Barbee, Joshua Castille, Daniel N. Durant, Treshelle Edmond, Sandra Mae Frank, and Amelia Hensley, all making their Broadway debuts. Also making Broadway debuts are Oscar winner Marlee Matlin and Russell Harvard, who saw the show twice in its Beverly Hills run and thought he’d remain just a fan—at age 34, he’s stuck between student and adult roles. Solution: He grew a beard to look older.

When Spring Awakening’s limited run ends on Jan. 24, 2016, Harvard will go directly into performing the role of Billy one more time at ZACH Theatre in his hometown of Austin. “I told myself that I would not do Tribes ever again,” he says, but it’s not because he doesn’t like it. “It’s just a very emotional, draining show. But in Austin, that’s a theatre company I always dreamt of working with, which I hope will open more doors for other Deaf actors in Austin.”

He also wants to do more musical theatre in the future (you can see his forceful ASL rendition of Sweeney Todd’s “Epiphany” on YouTube). “If you really want to be seen, musicals might be the best bet,” he says. “I directed Grease at the Texas School for the Deaf. We gave a two-night performance. It sold out. If you do something that’s familiar and it hasn’t been done in a while, you’re guaranteed to get audiences to come and watch.”

As great as all these opportunities are for Deaf actors, Seago and Harvard both say that what’s still missing in the theatre is Deaf writers telling their own stories. Seago, who hopes to start a Deaf writer’s lab in Seattle, thinks that one problem might be that workshops aren’t willing to pay for interpreters. Some Deaf writers are turning to the web to produce their own content. A new web series, “Fridays,” was created by Josh Feldman and Shoshannah Stern; they felt that Deaf characters on film and TV, let alone onstage, are often defined solely by their deafness, and they wanted to make a show in which the characters’ problems had nothing to do with their audiological status. And Fogel wrote the web series “Don’t Shoot the Messenger” with three Deaf people: McGinty, Andrew Fisher, and Onudeah Nicolarakis. “They are all tired of stories that are not necessarily about the issues they want to talk about,” Fogel says.

Deaf artists are also turning to social media. The hashtag #DeafTalent was started in response to hearing actors being cast in Deaf roles.

“#DeafTalent grew out of protest to become a celebratory hashtag,” says Giordano. “We’ve used it to showcase other actors and to keep each other informed.” Social media has contributed in other ways, he points out, as when videos of Lydia Callis, NYC Mayor Bloomberg’s ASL interpreter, went viral, portraying ASL as sexy and fun in the media. “The more media exposure, the more Deaf actors in Deaf roles, which gets more exposure, and so on.”

Linda Buchwald is an arts reporter based in New York City.