BOSTON—Shortly before 7:15 p.m. on a mild October evening, theatregoers lined up out the door of Boston’s Colonial Theatre and onto the sidewalk of Boylston Street. It’s a scene the palatial theatre has seen innumerable times since opening in 1900; though the attraction on this evening was the touring production of The Book of Mormon, the ornately gilded house has seen the pre-Broadway tryouts of canonical shows from Anything Goes to Porgy and Bess to A Little Night Music.

The pre-show buzz gave little indication that this Saturday-night scene was the eve of the theatre’s indefinite closing. After the weekend’s remaining shows, when the public next has access to the building, the sumptuous “ladies’ lounge”—whose working fireplace reportedly impressed one Katharine Hepburn—may be part of a brightly lit cafeteria for students of Emerson College.

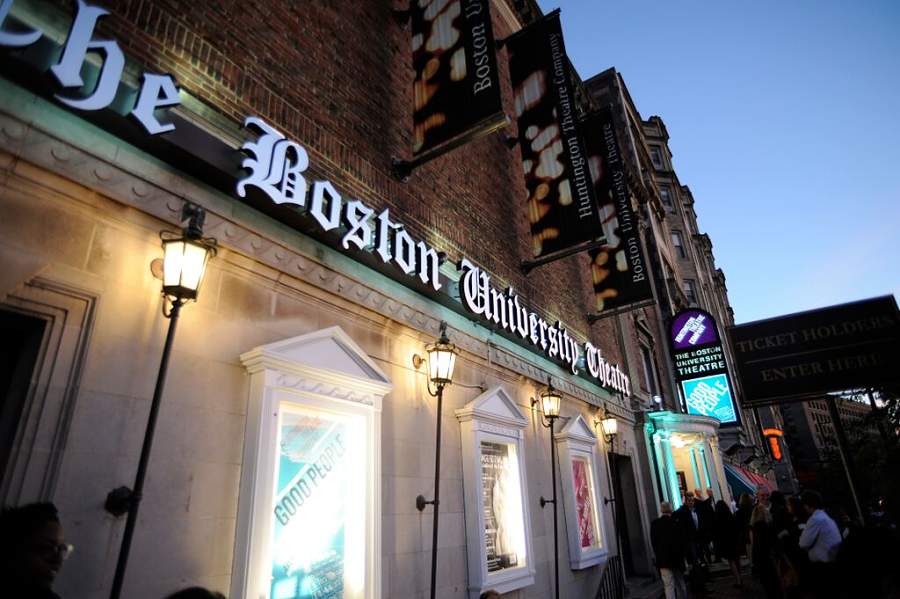

A furor broke out on the Boston theatre scene last week when the Boston Globe published details from architectural plans commissioned by the college, which purchased the Colonial in 2006. The plans would reportedly turn the space into a multipurpose student center, including a visitors’ center, a student café, and a black box theatre built upon the current stage. This news came a day after Boston University announced plans to sell its BU Theatre, which it had made available, rent-free, to the highly regarded Huntington Theatre Company since its founding in 1982.

The twin shocks left some wondering about the future of the theatre scene in Beantown, after a spell when much of the news around both the Huntington and Emerson had been positive. The Huntington won the 2013 Tony Award for best regional theatre, and Emerson has emerged in the last decade as a major player on the scene, renovating and reviving the old Paramount Theatre and Cutler Majestic Theatre—both a few minutes’ stroll from the Colonial—and creating a presentation/production arm called ArtsEmerson that has offered a stream of well-regarded productions, with an emphasis on internationally sourced, nontraditional shows.

The Huntington is presenting news of the sale of its home as an opportunity. The troupe made an offer on the property, which includes the 890-seat theatre and two adjacent buildings, says Michael Maso, the theatre’s managing director. But it couldn’t strike a deal with the university, which instead is putting the property on the open market with plans to funnel any eventual proceeds into a new student facility on its main campus.

The Huntington Ave. property is a prime piece of real estate in a hot market: It sits across the street from the city’s Symphony Hall and is surrounded by bars and restaurants that cater to the cultural elite, as well as students from nearby Northeastern University and the Berklee College of Music.

Maso says the Huntington wants to renovate the 1925 venue, which it likens to Broadway’s Booth Theatre, and would be an attractive partner for a commercial developer seeking to redevelop only a portion of the site. “It’s in the interest of the city to enable the Huntington to be able to do our work,” Maso says, “and to continue the programs and services we provide. I believe that by partnering with us, a developer will be able to get accommodations through the zoning process to allow them to make more money. It’s in everybody’s interest to allow a developer more leeway, if they in fact work to preserve the work of the Huntington.”

A capital campaign of $40 to $60 million would be in the cards, he adds.

“They’ve built a home in that space, and I certainly don’t want to see that building become anything other than a theatre,” says Jim Petosa, director of BU’s School of Theatre, “and I would love to have them continue and have a plan for how needful renovation can help to secure that building for decades to come.”

While BU and the Huntington are taking the opportunity to get their message out, the future of the Colonial has turned into a hot-button issue, and relevant parties there are clamming up. Emerson College declined comment for this story, instead directing American Theatre to a statement posted on its website. Broadway in Boston, a promoter who leased the Colonial for 10 years before Citi Performing Arts Center assumed control three years ago, also steered clear of potential controversy, declining to comment.

“The [Boston Globe] article is based on architectural drawings that the Globe obtained without Emerson’s permission,” reads the online statement from Emerson president Lee Pelton. “It represents only one of several options that the College is considering for the future use of the Colonial. One of several plans under consideration, represented in the drawings,” it goes on, “is to reanimate the Colonial as a multi-purpose theatrical performance venue, expand Emerson’s social and dining spaces, provide performance space for Boston’s burgeoning small theatre companies by creating a black-box theatre to complement the mainstage when it is not in use, and convert the 600-seat orchestra to a 300-seat modular, reversible dining area available to the Emerson community and its guests.”

According to further reporting by the Globe, a letter signed by Emerson arts faculty and presented to Pelton blasted the plan: “Any alteration to the Colonial Theatre or deviation from its intended use would destroy its status as a significant cultural landmark of Boston and its recognized national legacy.”

The Colonial is decked out with stately chandeliers, elaborate murals, and copious amounts of 24-carat gold leaf. Though the model that sustained commercial houses through much of the 20th century has changed, and Broadway-bound shows these days are more likely to spring from the American Repertory Theater across the Charles River in Cambridge, or summer theatres in the Berkshires like Williamstown Theatre Festival, the theatre lore at the Colonial is thick. As the story goes, the cast of a new Rodgers and Hammerstein musical called Away We Go! once gathered on one of the lobby’s grand staircases to hear a new song the creators wanted to insert that night; the song was called “Oklahoma!’’

The number—and the name—stuck.