NEW YORK CITY: Next week would have been Arthur Miller’s centennial, and New Yiddish Rep will celebrate by recalling another milestone: The 1951 premiere of Joseph Buloff’s Yiddish version of Miller’s towering 1949 classic, retitled Toyt fun a Salesman. New Yiddish Rep, whose staging runs Oct. 8–Nov. 22 at the Castillo Theater, will be adapting Buloff’s translation for their production, which will be performed in Yiddish but with English supertitles.

The purported Jewishness of Willy Loman and his family has long been a matter of speculation and debate, with Miller himself—who was raised in a thoroughly Jewish milieu—coming down on either side at various points throughout his career. But when he first wrote the play, he clearly intended Death of a Salesman primarily as an American story, and thus downplayed any signifiers that would mark the Lomans as ethnically or religiously specific.

But when the curtain rises at the Castillo, there’s no question about the Lomans’ culture or religion. Their use of Yiddish even suggests another level of otherness.

“Yiddish is the language of immigrants, and Willy—who may even be a refugee, though that’s not stated—knows he is different,” says Avi Hoffman, who is tackling the title role. “When Willy says, ‘They laugh at me,’ that has added resonance.”

What’s more, Hoffman says, “Performing it in Yiddish feels natural.”

David Mandelbaum, the company’s founder and artistic director, agrees. “The Yiddish has a particular music that conjures up the Wandering Jew. And what is the traveling salesman but a wanderer, someone who is dragging a pushcart?”

Mandelbaum is attracted to theatre that works on both literal and metaphoric levels, nowhere more pointedly than in New Yiddish Rep’s stunning production of Waiting for Godot, performed in Yiddish at the Castillo in 2013, then as the kickoff production at Happy Days Enniskillen International Beckett Festival in Northern Island in the summer of 2014. The play was reprised yet again as part of the Origin’s 1st Irish Festival at the Barrow Street Theatre in Sept. 2014.

Initially, the creative team on the Yiddish Godot wanted to set it in a post-Holocaust universe inhabited by concentration camp survivors, but the ever vigilant Beckett estate put the kibosh on that. But the play hardly needed to be explicit about the association: That resonance was evoked anyway, not only when the characters spoke Yiddish but when they spoke of ashes and millions who were dead.

“That gave the drama a context and clarified what it’s about,” Mandelbaum says. “Beckett, who wrote Godot in 1947–48, had to be drawing upon the previous 10 years of history.”

Mandelbaum, who donned his actor’s hat to play the earthy Estragon, said the Yiddish cadences and physical gestures identified with the language made the material more accessible to everyone.

In addition to adapting classics into Yiddish, New Yiddish Rep, now in its eighth year, also produces well-known and obscure works originally written in Yiddish. But the company’s central mission is forging vital theatre that can reach a broad-based audience, not only Yiddish speakers. English (and sometimes Russian) supertitles are provided. As the number of living Yiddish speakers dwindles, it’s important, says Mandelbaum, to show how singularly expressive and modern the language is.

“Though Yiddish theatre has a tradition of performing masterworks, it’s now identified with musical revues and light entertainment,” he says. “Yiddish is a riveting language and compelling theatre, but it’s in danger of becoming archived.”

It may also be in danger of extinction in its very heartland, adds Salesman‘s Romanian-born director, Moshe Yassur, who notes that Romania’s State Jewish Theater now has only has one Yiddish-speaking actor on board. The handful of Yiddish-speaking theatres around the globe may be facing similar fates.

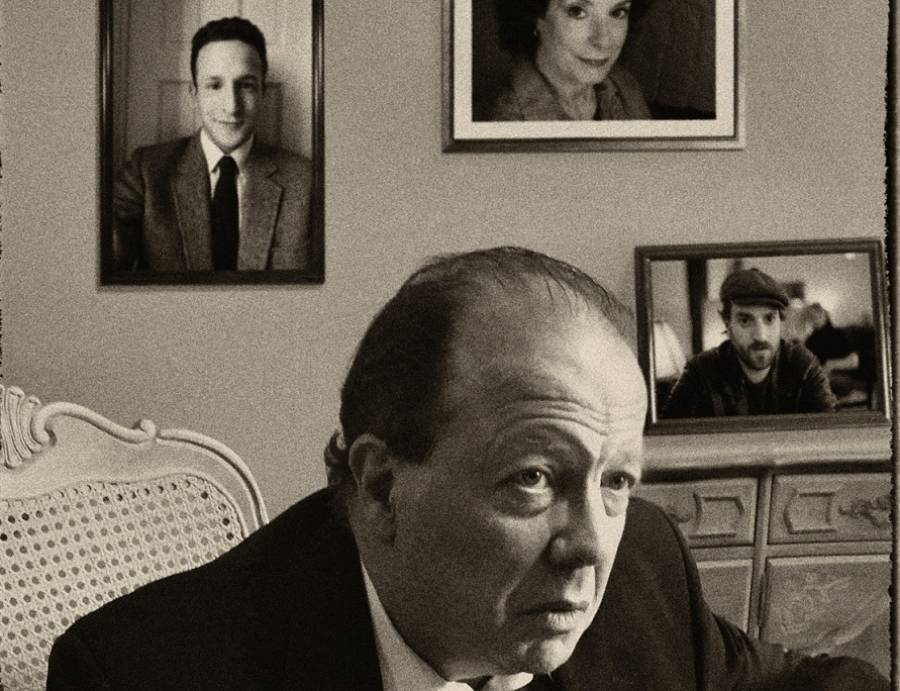

Most of the actors in New Yiddish Rep are Yiddish speakers with profound connections to the Jewish community. For Hoffman, the son of Holocaust survivors, Yiddish was his first language. Daniel Kahn, who plays Biff, learned Yiddish later in life as his aesthetics and politics evolved. The Detroit native, who now lives in Berlin, is best known as a composer and singer performing an array of protest songs in Yiddish and English, with a dash of Brecht and klezmer thrown in for good measure.

By contrast, Shane Baker, who plays Charley, is a Kansas City–born Episcopalian who happens also to be a nationally recognized Yiddishist. He served as Godot’s Yiddish translator, in addition to playing the philosophical Vladimir. Baker notes that a Yiddish-speaking Charley adds a layer to his relationship to Willy, precisely because they share an ethnic and cultural background and literally speak the same foreign language. “Thanks to that bond there’s now an added element of conflict, though he still can’t stand him,” says Baker.

But no conflict in the play is more intense than the father/son blowup that climaxes the play, and which packs an extra emotional wallop in Yiddish. The father sacrificing his life so that his sons can attain the highest level of achievement has very deep meaning for Jews, says Yassur.

Explains Kahn, “Willy wants Biff to submit to a cult of excellence as a way out of poverty. Part of the American Dream demands that you give up the most important part of yourself in order to become a commodity. Willy buys what that’s selling; Biff doesn’t. I had conflict with my own father, who was in marketing and very much bought into the notion of climbing up the ladder of success.”

What are New Yiddish Rep’s next rungs? Mandelbaum says he would like to see the troupe evolve into a repertory company, producing plays in rotation, alternately in Yiddish and English. But at the moment his thoughts are focused on Salesman, and he’s anticipating the unique role it will play in a New York theatre season that also includes productions of The Crucible and A View From the Bridge.

“The timing is right,” he says. As Buloff rendered Linda Loman’s famous exhortation that “Attention must be paid”: “Gib achtung.”