Christopher Hitchens was an atheist—just one of my many disagreements with him—but he was right about one religious matter: The King James Bible is something of a linguistic miracle, and Western civilization is fortunate (on balance) to have it. This 17th-century translation-by-committee project, an effort to elevate Christianity’s central text into a piece of writing at once lofty and vernacular, demotic and divine—in short, to make a book worthy of both its subject and its age—ended up, at Hitchens once aptly put it, “rather more than the sum of its ancient predecessors, as well as a repository and edifice of language which towers above its successors.”

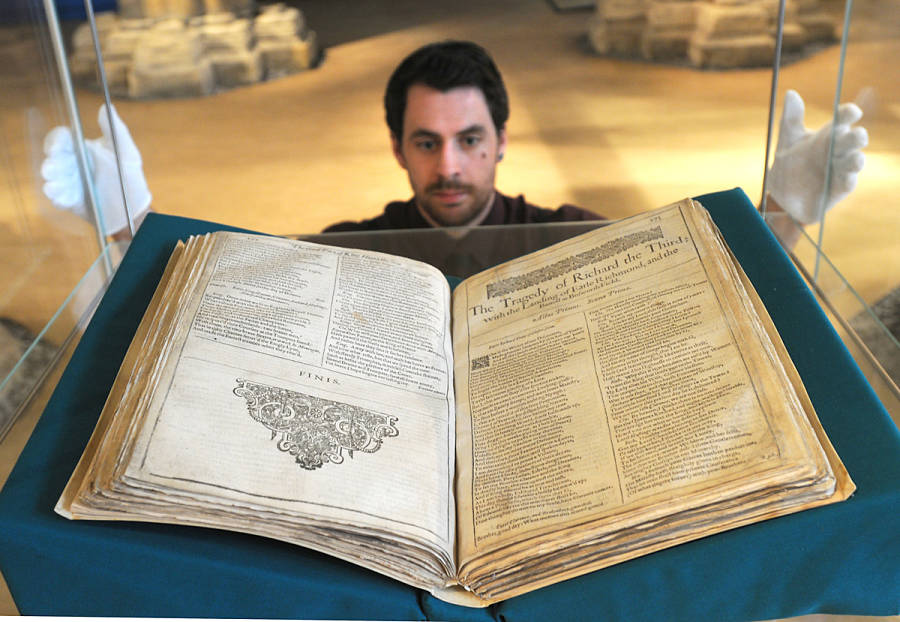

This could also describe the work of one of that translation’s singular contemporaries, an ambitious actor/playwright named William Shakespeare. There’s no point in guessing at proportions here, but it’s fair to say that a lion’s share of the language we still speak and write and dream, even or perhaps particularly in America—where the first Bibles were in English, and Shakespeare has seldom been scarce onstage—can be traced back 400 years to two Williams, Tyndale and Shakespeare.

But much as I cherish the King James Version, and consider more contemporary translations of the Bible not replacements but companions, my theology (thankfully!) doesn’t depend on it. I guess if I thought of the Bible entirely as man-made literature, I might privilege the KJV’s marvelous words over its deeper portent, as Hitchens did. But as I’m ultimately more attuned to the spirit than to the letter, I remain something of a relativist about the fixity of the scriptural text—as indeed Shakespeare’s contemporaries must have been, having grown up with the plain English of the Geneva Bible only to be faced, in 1611, with the explosive, authoritative prose poetry of the KJV. If I may blaspheme freely, I imagine that reading and/or hearing the King James Bible for the first time must have seemed, for Jacobeans, as mind-expanding as hearing Bob Dylan or Biggie Smalls (or what the heck, I’ll say it: Hamilton) for the first time was for many of us.

So if I’m open to translations of a text I consider sacred but only incidentally a work of literature, what about of texts that are primarily man-made literature, if possibly no less sacrosanct? I’m circling back to Shakespeare, and to the recent news of Oregon Shakespeare Festival’s long-brewing “Play on! 36 playwrights translate Shakespeare.” The idea is not a new or even radical one, but it has probably never been done so comprehensively or methodically: OSF will hand the canon over to contemporary dramatists (and dramaturgs) for line-by-line nips and tucks of the original language into “modern English.”

The outcry that has greeted this announcement has been as ferocious as you might imagine, or more. Though artistic director Bill Rauch and literary manager Lue Douthit have taken pains to say these aren’t replacements but companion pieces, and have preemptively assured critics that these new “translations” will not be the versions of the Bard that will show up on OSF’s stages (for the time being, at least), their proposal has been treated as the worst kind of sacrilege and profanation, a sign of the cultural end times, a capitulation to dumbed-down mass culture, etc.

I’ll confess that I am of two minds about this myself. On the one hand, I am envious of some of my bilingual colleagues, who can see or read Shakespeare in Spanish or French or Russian and grasp it with more immediacy than I probably ever will, because most such translations use contemporary language. (I’ve even heard that contemporary productions of Ibsen in Oslo update his fin-de-siecle Norwegian into a more contemporary idiom.) So while I’ve lapped up plenty of lively adaptations of Shakespeare that departed mostly or entirely from his original language, I do wonder: What would Shakespeare’s language sound like, mostly untouched but with his more arcane vocabulary and locution unwrinkled? I’m willing to listen.

On the other hand, as with several King James Bible verses, there are many Shakespeare speeches I cherish exactly as they are, like song lyrics, and I don’t especially welcome the thought of hearing them differently (though now that I think of it, I did love Theatre of NOTE’s “bad” Hamlet, a 2003 production of the whackadoo First Quarto, directed by OSF alum Andrew Borba—in part because I knew it was absolutely no threat to the primacy of the Folio). I’m sympathetic to the view, expressed by several and felt by countless others, that Shakespeare’s plays irreducibly are his words, and vice versa; if you change the words it’s not Shakespeare—it’s just not. This is the ultimately inarguable fact about all translations of great writers: The original language, in which the writer did his thinking and dreaming and crafting and inventing, is always lost in the transaction.

What OSF’s project intends to do, as best I can tell from what they’ve said (and from the nimble, limpid new translation of Timon of Athens by Kenneth Cavander I’ve just read), is to lose quite a bit less than all the language, while retaining or clarifying the sense of it—in other words, most of the letter and certainly all of the spirit. On my recent visit to OSF, I spoke at some length with Douthit about the project, and she did her best to clarify, as well.

“We have a longstanding patron, Dave Hitz, and he has had a dream, and the dream is to understand Shakespeare in the moment of hearing it,” Douthit said in her office, in front of a dry-erase board matching Shakespeare plays with the names of playwrights and dramaturgs. Hitz, who made his fortune as a cofounder of the data management company NetApp, is no rube; as Douthit said, “He and his family having been coming for decades. He studies the plays, he reads them, and yet, when he comes, there’s language that’s challenging. There is with me, too, and I’ve been here for 22 years. I think if any of us are being honest would say: There are things we hear and don’t understand.”

This is true enough, as the linguist John McWhorter memorably pointed out in our pages a few years ago; McWhorter also called for translations that would be “richly considered, executed by artists of the highest caliber well-steeped in the language of Shakespeare’s era.” Douthit agreed; and the artist she approached with the idea was Cavander, a venerable translator of Greek plays, among other clasics. Douthit asked him what he thought of “translating” Shakespeare. “There was a pause,” Douthit recalled, “and he said, ‘This could be a career ender.’ I said, ‘We’re too old, Kenneth.’ He said, ‘Yes, you’re right.’ So he took it on.”

While Douthit has admitted that the word “translation” suggests something more invasive than what the commission asks of these playwrights, the word “adaptation” is also wide of the mark.

“It’s translation because it’s focusing on the language only,” said Douthit. Her mandate to Cavander, as to all the commissioned playwrights, is to “put the same amount of pressure on language as Shakespeare put on his—that means rhetoric, rhyme, meter, metaphor, image, action, character, everything that’s there. It is not to be No Fear Shakespeare; it is not to be paraphrased. I don’t want your politics and I don’t want your regionalism. I just want you to have fun, like an exercise. You’re not cutting; you’re not editing, you’re just going in line by line.”

Cavander’s Timon had a successful premiere last year at Alabama Shakespeare Festival, which Douthit called “terrific. The language was muscular and beautiful and clear when it’s supposed to clear.” Which brings up an important distinction: “We don’t want clarity if somebody’s trying to be obscure. Sometimes we’re vague because we really don’t want people to understand what we’re saying.”

The goal, Douthit said, is to come up with producible new versions of the plays—and for that, she posited, you need playwrights.

“At first it was going to be all translators, and I only knew three,” said Douthit. But then she realized that having dramatists and theatre practitioners (most of the commissionees are playwrights, though two, Lisa Peterson and David Ivers, are primarily directors) made more sense. It would also represent a long-overdue intervention.

“A dramatist’s mindset is in the center of the conversation now, for the first time in 400 years,” said Douthit. “Think about it: We have dramaturgs, directors, actors, designers, scholars working on Shakespeare all the time, but you don’t have a dramatist in the middle of that conversation.”

I’m resolved, in short, to take a wait-and-see-and-hear approach. I trust Rauch and OSF implicitly, and the list of playwrights and dramaturgs they’ve enlisted impressive and fascinating (Taylor Mac and Titus Andronicus? That I’ll pay to see). Finally, I think I have an answer for the rhetorical question I posed earlier: How do I feel about something that is primarily literature, not scripture, getting a makeover? Ah, but Shakespeare finally isn’t literature, or literature only, but theatre, which ever and always lives in the present tense. If you’ll indulge me an overtly Christian analogy (because I do think of theatre, after all, as a kind of communion), we would probably do well not to mistake the liturgy for the sacrament—to privilege the word over the breath and the body. Words without thoughts never to heaven go.