As much as anyone in the field, production photographers understand the theatre’s essential impermanence. They know it’s an art form that can’t last, that can never quite be captured or recorded, yet that’s exactly what they’re trying to do. They’re attempting to document work that disappears the moment the lights go down.

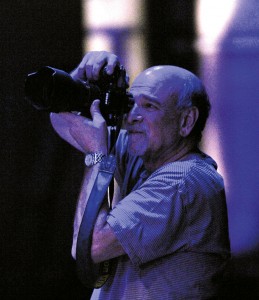

“You’re shooting an archival thing here,” says Stan Barouh, a Washington, D.C.–based photographer who takes pictures for Woolly Mammoth, Theater J, and the Olney Theatre Center, among others. “It’s a sandcastle, and you want to get a picture of the sandcastle before the tide comes.”

BreeAnne Clowdus, whose Atlanta clients include Actor’s Express Theatre Company, Theatrical Outfit, and Serenbe Playhouse, took up her trade precisely because of that tide.

“It has always struck me as a little bit tragic that after all the effort that goes into making a theatre production, it disappears after three weeks or a month,” she says. “My passion really comes from all of that effort.”

Granted, it can be easy to forget the significance of production photographs when you’re scrolling past them in your Twitter feed or glancing at them in the paper. When you just want to know what the critics thought of Twelfth Night, the shot of Malvolio pointing furiously at Feste may not be the first thing you notice.

Still, the images are working on you. They’re shaping your understanding not only of the show being pictured, but also of the artists and producers involved. They’re guiding your perception of the work you might see this weekend, and they’ll help define your memories of productions that have closed.

All that puts a remarkable amount of pressure on the photographers. It’s great to know you’re capturing the sandcastle; knowing how to capture it requires a vast yet particular set of skills.

Just ask anyone working on a show: “A theatre needs a photographer that understands their spaces, their aesthetic, their brand, and their artistic identity,” says John Zinn, director of marketing and communications for Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theatre Company. That means that show photos, whether they’re for the press or the archives, have to do multiple things at once. As Justin McCarthy, Woolly Mammoth’s communications coordinator, explains, “An ideal production photo does three things: captures the spirit of the play, entices the potential audiences to come see the play, and speaks to our mission.”

So how do production photographers capture all those essences in a single still frame? It helps to remember that for all their artistry, they’re not working for themselves.

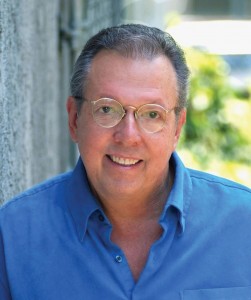

“What I do is a service,” says Joan Marcus, who is such a fixture in the New York scene that she received a special 2014 Tony for Excellence in the Theatre. “The art in what I do is in interpreting other people’s work. It’s not my vision. It really isn’t. So right from the get-go, you’ve got to check your ego and just go with it.”

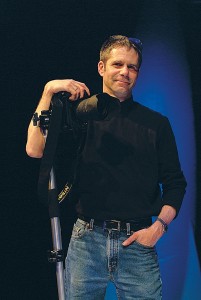

Staying true to a production’s vision may mean ignoring conventional wisdom about what makes a good picture. This summer, for instance, Michael Brosilow—whose long career includes shooting dozens of productions for Windy City companies like Steppenwolf, the Goodman, and Chicago Shakespeare Theater—shot a stage adaptation of The Birds for Chicago’s Griffin Theatre. “It was an incredibly dark show,” he says, referring to the scant illumination provided by lighting designer Eric Vigo. “Now, I can go in there in the computer and pump it and make it look ‘normal,’ but that’s not the designer’s intent. It was meant to be a dark show, and it’s my job to keep it as true as possible. It might create problems for the press guy, but I’m adamant about being very true to the designer’s intent.”

On the other hand, it’s crucial to understand not only how theatrical lighting and projections work, but how to make them work to your advantage, since your medium is print (or the web), not the live theatre experience. As Barouh says, “I’m constantly dialing in light settings. I’m trying to make faces look like face colors and not orange or blue. You don’t notice when you’re watching that a night scene looks a little blue, but when you shoot it, it’s totally blue. You have to dial it in so that it still looks like a night scene and also makes the actors look okay.”

To a large extent, honoring a show’s ethos isn’t an abstract mandate; it’s a question of technical expertise. “Your shutter speed, your film speed, and your aperture—you have to balance those tons of times in a minute,” says Clowdus. “Production photographers should really take a lot of time to learn their instrument. Your camera is all you have.”

What you use that fine-tuned instrument for, though, has unavoidable dramaturgical elements. Whether they’re shooting a live performance or assembling stand-alone “set-ups” of particular scenes, production photographers have to sense a show’s tone and narrative beats. Otherwise, they’ll miss all the key moments.

In a live shoot, especially, this sensibility needs to reach an almost superhuman level. Though some of them read scripts or chat with creatives before covering a run-through or performance, the photographers interviewed for this story say they rarely get a chance sit down and watch a show through before they whip out their cameras. And unless they’re working on big-budget extravaganzas, they don’t get the chance to shoot multiple times. Instead, like photojournalists covering a one-time news event, most of them walk into a theatre cold and get exactly one opportunity to understand—and capture—what they’re seeing.

“I’ve always loved the challenge of it,” says Brosilow, who was among the first Chicago-based theatre photographers to shoot live performances. “It’s kind of like shooting sports under bad light. You’ve still got to get the ball on the fingertips. You’ve still got to catch that moment, but you’ve got to do it under low light or no light or bright light. It’s still challenging, and it’s always different.”

It’s almost always athletic, too. “It’s exhausting!” says Clowdus. “It’s like a two-and-a-half-hour workout. I’ll lay on the floor to get low angles. I’ll squat a lot. There’s a lot of running.”

Asked about the physical demands of her work, Marcus quips, “I don’t have knee issues or shoulder issues or back issues, and I’m really lucky, because I’m not young.”

Meanwhile, since press outlets need photos early in a run, live shoots often happen at dress rehearsals. “That means that a lot of times, I’m coming at a bad time,” says Ed Krieger, who has decades of experience working with Los Angeles companies like Theatre @ Boston Court, Skylight Theatre Company, and the Fountain Theatre. “If the show is not ready, they come in with a lot of raw nerves. I have to work with all that, and it’s tricky, especially in the 99-seat theatres. When I have to shoot live, I’m in the front row. I’m practically onstage with them, and I’m trying to be as subtle as I can. But then all of a sudden, there’s the shot, and it’s boom-boom-boom-boom! I’m sitting there going, ‘Oh, it’s so quiet, and I don’t want to take this shot!’ But I’ve got to take it.”

Or, as Barouh puts it, “I’m in there running around, making noise, constantly moving. If you can act around me, then your audience is no problem.”

Perhaps surprisingly, the photographers all seem more concerned about disrupting the actors than missing major moments in a play they’ve never seen before. “I don’t even think about that part of it anymore—am I going to miss this or that,” says Marcus.“A lot of it’s subconscious, and you go into a zone. You follow the flow, and of course you miss things, but that’s just how I do it.”

Brosilow echoes her, saying, “The show starts, and you just get into the rhythm of it. It’s a matter of anticipating stuff and trying to be in right spot at the right time. I’ve worked with some directors so many times that I can almost predict where they’re going to go with a show. Some directors are three chords, and some are like jazz.”

In fact, some theatre companies actually prefer their photographers to follow a production on instinct.

Brian Polak, marketing and communications manager for Theatre @ Boston Court, marvels at Krieger’s intuition: “He comes in to photograph without ever having seen the show, and that fresh perspective allows him to take photos we may not have imagined, or from an angle we haven’t considered.”

Polak’s comment underscores another fundamental element of production photography: trust. Because it’s so important for photographers and theatre artists to understand each other, they tend to collaborate for a long time: Brosilow has worked with Steppenwolf for decades, for instance, and Barouh started shooting for Woolly Mammoth in the 1980s. Those rich relationships can bring unexpected dimensions to everyone’s work.

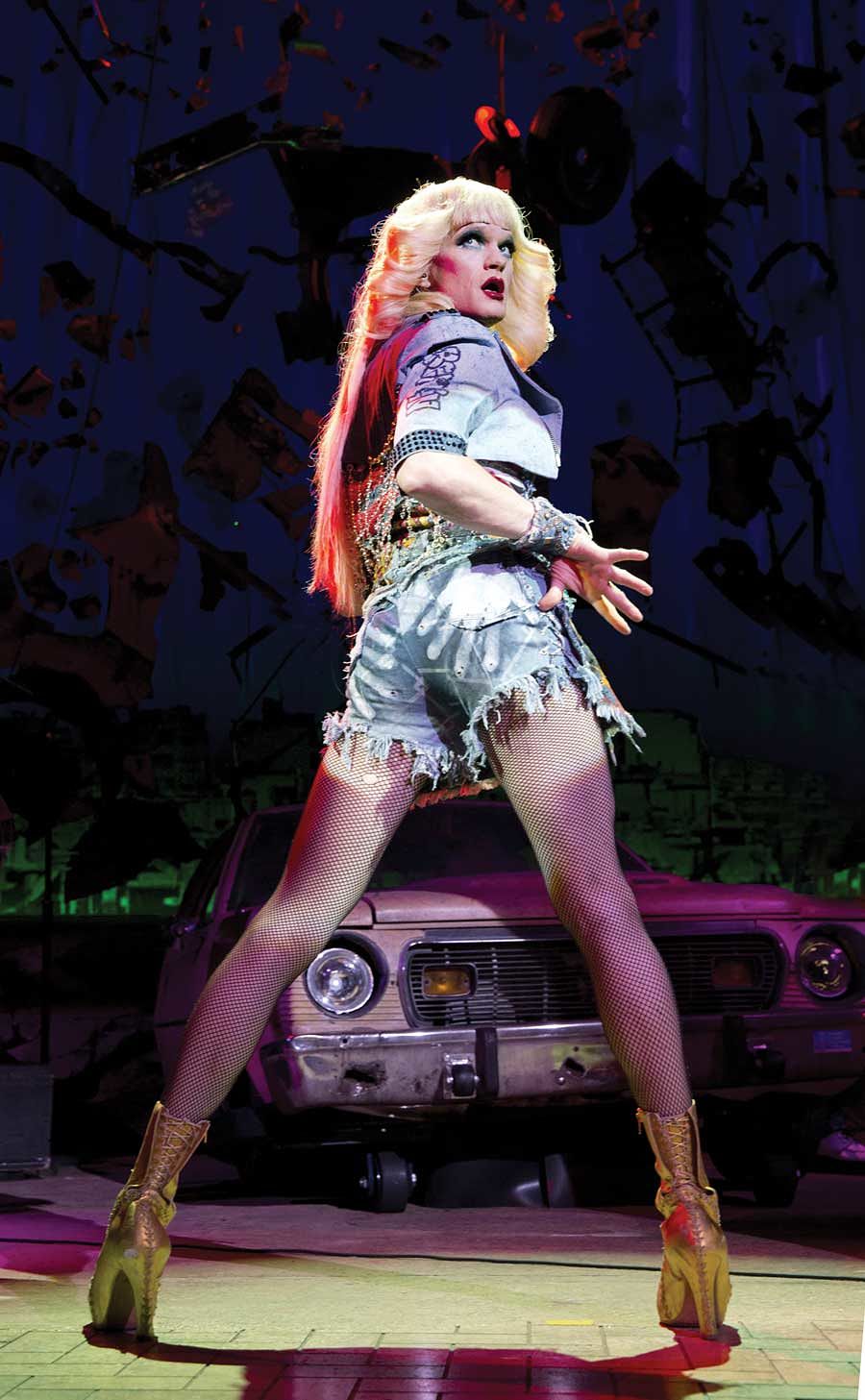

That’s apparent in Clowdus’s portfolio. Along with production photos, she also creates advertising and PR images for theatres that appear long before the shows themselves. Since sets and costumes haven’t been constructed at that point, she often crafts movie poster–style one-sheets of the actors that communicate some essential element of what a production will be. The results are frequently eye-popping and high-concept—last year’s pics for Serenbe’s Oklahoma! look like vintage postcards colorized by Ted Turner—and, as Clowdus herself admits, they veer toward “nudity, blood, or possibly baby oil.”

These posters wouldn’t work, Clowdus says, if she didn’t intimately know her clients. “She has a knack for drawing something out of actors,” says Freddie Ashley, artistic director of Actor’s Express. “She has this way of putting actors at ease and making everyone feel like the sexiest, smartest, and most dynamic versions of themselves. Her shoots are like going to the coolest cocktail party in town.”

That sense of connection can go the other way, too. “Sometimes the job is especially satisfying because I’ll know the person, and it’s a breakout part for them,” says Krieger. “There was a show at Boston Court called God Save Gertrude, and the leading lady [Jill Van Velzer] is a person that usually does, like, Julie in Carousel. But this time she was this punked-out rocker with track marks that played guitar. I really enjoyed that she could have photos of that.”

Barouh gets even more expansive when he discusses why he likes his job. “When I shoot, I’m laughing, or I’m even crying sometimes,” he says. “I’m really emotional with it, and the actors really respond to it.”

He continues, “There are pictures I love, but it’s all their gift to me. The actors are up there doing their job, and the designers have done their job, and you feel like, ‘I just walked into this, so I’d better not fuck this up!’ That’s the basic thing to remember: Don’t fuck it up. Be exposed. Be sharp. Be in focus. And take some good shots.”

New York–based arts reporter Mark Blankenship writes frequently for this magazine.