NEW YORK CITY: Theatregoers looking to congratulate the playwright of Prospect High—Brooklyn might not know where—or with whom—to start. Copies of the play’s workshop edition list no fewer than 12 individual authors, and that’s not counting a lengthy acknowledgments page that extends its credit to a myriad of directors, workshoppers, and educational organizations.

So who did write Prospect High?

“The process was completely organic,” explains Daniel Robert Sullivan, the primary playwright who collaborated with nine New York City students on devising the play, which consists of a series of vignettes about a group of Brooklyn high schoolers dealing with teenage trials and tribulations. The play will tour to 24 high schools all over the country, with the cast of each production comprised of students from each school, in a touring model fashioned after the National New Play Network rolling world premiere.

Sullivan says the play began as “a gem of an idea”: to write and produce a socially conscious, easily producible, flexible-cast play for teenagers that would be truly reflective of life in modern American high schools. With a rehearsal space and enough funding, he thought he could gather together a group of local students for regular monthly meetings and write a play based on their collective experience. Roundabout Theatre Company’s Education Department was quick to lend its support, and, by the fall of 2013, workshops for Prospect High were underway.

Sullivan and his collaborators—all of them students from public high schools in New York City—met at Roundabout on a regular basis, swapping stories of in-class conflicts and after-school confrontations. “We set up a space where anything could happen,” says Sullivan. “I essentially pulled out every trick I have to generate material.”

Grants from the Fox Foundation and Theatre Communications Group allowed Sullivan to pay his teenage collaborators for their time. The financial incentive, he thinks, established a sense of artistic responsibility for both parties. “I had to treat them as professional artists being paid for their creative work,” he says. “Their job was to show up and participate.”

Sullivan met with the students for a total of nine months. For the first four months, Sullivan and his collaborators simply met to talk and discuss issues the students faced at school. All of these meetings were recorded “Chorus Line-style” for Sullivan’s reference, as he was worried that differences in age and race might leave him ill-equipped to accurately represent the voices of his young, ethnically diverse colleagues.

Much of the dialogue from these recordings is quoted verbatim in the play. Sullivan calls his playwriting technique “theatricalization of the truth.” While none of the play’s characters—there are anywhere between 5 and 18 of them, depending on the size of the production—exactly correspond to the real-life students who inspired them, “Every scene in the play comes from something in reality,” Sullivan explains.

“I always made sure that I was an equal participant,” Sullivan insists of his role in the writing process. “I can’t pretend to understand the day-to-day experiences of these students. But I was interested in understanding: What’s your motivation when you express your opinion here? To defend yourself? To attack somebody? I want to know where they’re coming from. And that shows up a lot in the play, this different sort of worldview.”

He hopes the same for the play’s adult audiences. “I want to get them interested in these teenage experiences a little bit more, to get them to try to understand,” he says. Sullivan has previously worked as a teaching artist for the New York public schools system, and he “wants the general population to say, ‘Wow, we don’t see these people onstage all the time. These characters don’t look like me. And yet I’m really interested in their stories.’ That’s what I’m hoping will happen.”

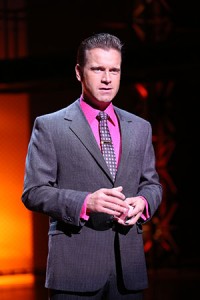

After an Equity workshop with Roundabout in April 2014, performance rights to Prospect High were granted to 24 individually selected public schools for a rolling national tour, the first of its kind at a secondary-school level. Sullivan’s demanding schedule—he’s currently performing six nights a week in a Las Vegas production of Jersey Boys—made it impossible for him to catch the tour’s first performance at Broad Ripple High School in Indianapolis, but his wife and daughter planned to drive out from their extended family’s home in Cincinnatti for the premiere.

Teaching artist, father, and husband in New York, performer in Nevada, and, now, a nationally produced playwright—how does Sullivan manage?

He laughs. “It’s just how I roll.”