WASHINGTON, D.C. and DALLAS: Both Meg Miroshnik and Karin Coonrod understand the importance of language to Elizabethan theatre, though in two new works the playwrights wield words and wit in different ways.

For texts&beheadings/ElizabethR, now at D.C.’s Folger Theatre through Oct. 4, in advance of its run at Brooklyn Academy of Music, Oct. 21–24, Coonrod employs Elizabeth I’s letters, speeches, prayers, and poems to provide a “kaleidoscopic” view of the linguistically obsessed queen (she spoke six languages). Accordingly, four women play the role, with one of them, Cristina Spina, performing the words in Italian. Many of the texts come from the Folger Shakespeare Library, where the show is running as part of the D.C. Women’s Voices Festival, in a production in association with Compagnia de’ Colombari.

“It’s really trying to find her voice, because she created a kingdom of words into which Shakespeare entered,” explains Coonrod. “There’s been a real movement in the last 10 years of people interested in Shakespeare, and Shakespeare inherited a language that she played a huge part in creating.”

Miroshnik took a different route for her play The Droll {Or, a Stage-Play about the END of Theatre}, now in its world premiere at Dallas’s Undermain Theatre, Sept. 22-Oct. 17. Instead of using extant texts or iambic pentameter, Miroshnik developed her own verse-based language which she calls “Drollspeak” for the play, about a troupe of players in 17th-century Puritan England during the years when theatre was illegal.

“The hope for me is that audiences will invest more deeply in the play for having to do a little bit of work to understand it,” Miroshnik explains. “That’s always my experience of seeing Shakespeare. I’m always exceedingly proud of myself if I get a joke.”

The language also creates the world for Miroshnik, in much the same way that it might have for Shakespeare’s audience. An author’s note in the script calls for minimal sets and props, and the Undermain production is accordingly very bare, as the words alone are meant to transport the viewer. In Elizabethan times, playhouses like as the Globe employed little decoration, and Miroshnik is aiming for a similar feeling. “The joy of seeing theatre is stretching imaginative muscles,” she adds.

Coonrod structured her play into four movements, one for each of the actors who plays Elizabeth and for the four textual forms (letters, speeches, prayers, poems). Coonrod says she took inspiration from Gertrude Stein and James Joyce in formatting the show, and that the action is not chronological.

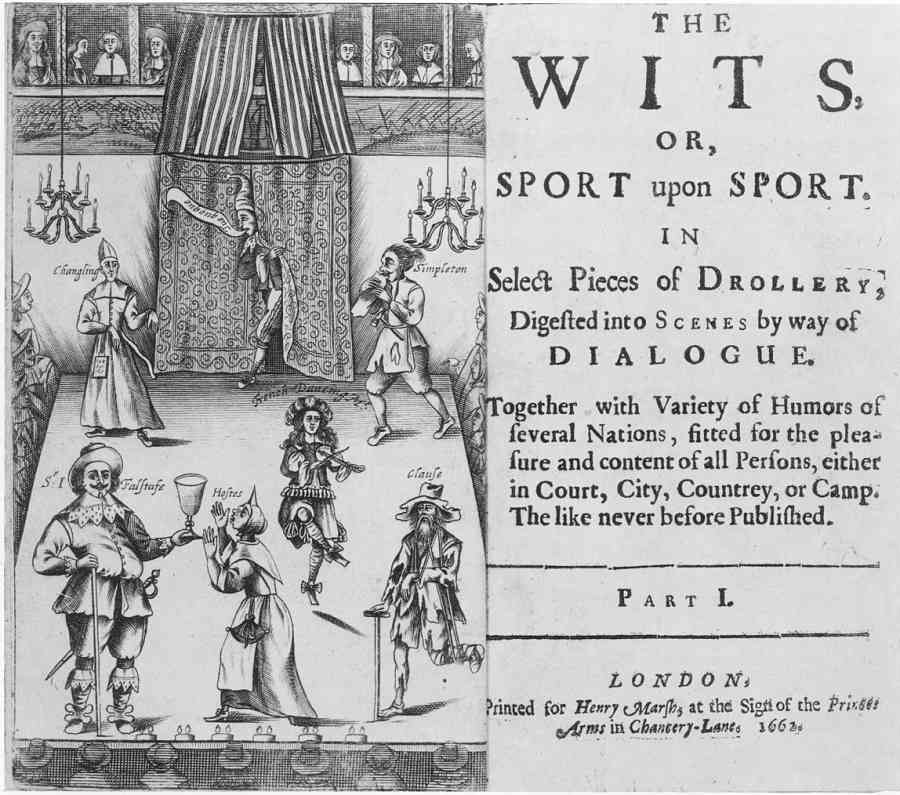

Miroshnik took the name of her play from the name for the comic sketches that were strung together into full evenings—typically a series of “greatest hits” from from popular plays (think the gravedigger scene in Hamlet). The style was popular as a kind of semi-legal stage samizdat during the Puritan closure of theatres. Taking her inspiration from Francis Kirkman’s frontispiece drawing for a 1662 collection called The Wits, which included Falstaff, Bottom, and others, Miroshnik’s play conjures a company of Elizabethan archetypes, a bit like a commedia troupe.

But she’s not just after quick laughs. “What would it have been like to fall in love in theatre at time when theatres weren’t open and when it wasn’t legal?” Miroshnik wonders. “It felt really urgent and contemporary to think about, How does the medium go forward with aging audiences?”

The Droll started while Miroshnik was at Yale as a “bake-off” assignment from Paula Vogel. Vogel’s famous writing challenge gives writers inspiration texts, certain elements that must be included—and 48 hours to write a play. Miroshnik’s inspiration text was The Tempest. Though Hamlet is now the main text referenced in the play now, there are still some Tempest remnants—one of the characters talks about playing Caliban.

But don’t ask her about her scholarly research for the show. Miroshnik did a lot of reading when she first started writing it, but then strove to forget a lot of it to create an essentially fictional world. When she did a workshop at the Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival, she was startled to see it performed for and by Shakespeare experts. “People were laughing knowingly at moments that I had forgotten were paraphrased echoes of Shakespeare,” Miroshnik says.

Coonrod, on the other hand, clung to the research. While there are some original words of her own, Coonrod mined the archives at the Folger and elsewhere. She says she’d been interested in pursuing something about Elizabeth for several years, and has been accumulating books and materials for a while. “I love doing real research and looking at the stuff—it’s very moving,” she says.

Both plays also explore the role of gender in the Elizabethan era. For a time period named for a woman who adored the theatre, it seems almost ironic that women weren’t allowed to perform on stages for most of the period, and all of the (at least well-known and produced) writers were male.

Miroshnik has addressed this by making her casting gender-fluid. The character of Thomas—“the male player of women’s parts”—has been cast as a man at the Undermain but can go either way, while the young boy Nim, “the theatrical Fanatick,” can also be cast either way—and is played by a woman in this production. “I love the theatricality of both choices,” says Miroshnik.

There’s also a moment in The Droll where one of the female characters is given the opportunity become as the first woman to appear onstage. But in a world where performing is punishable by death, putting a real woman onstage is the least of the troupe’s worries.

For her part, Coonrod sees Elizabeth I’s success as related to her being an astute observer, a position that contrasts to other women of the time who didn’t fare as well. “I have a feeling that Anne Boleyn talked too much, and that got her beheaded,” says Coonrod. “What gets a lot of women ‘beheaded’ in our culture is when we have sharp tongues and we say too much and we don’t watch a little more.”

Miroshnik says that one of the thrills of writing The Droll was that she almost began to feel a kinship with the Bard.

“I’m not trying to write my own Shakespeare—I’m writing my own language as if I were writing alongside Shakespeare, and there’s something that’s really exciting about that as a woman,” says Miroshnik. Noting that the preponderance of contemporary Shakespeare revivals may mean fewer productions of new plays by women, she draws inspiration from the lesson her fictional troupe learns in regard to the tragedy of the melancholy Dane.

“It’s set up as the most important vessel for this theatrical tradition,” she says. “And in the end, it turns out that theatre can survive without Hamlet.”