“Why is it that there are so few women playwrights? And why is it that the infrequent plays produced by women playwrights rarely attain high rank? The explanation is to be found in two facts: First, the fact that women are likely to have only a definitely limited knowledge of life, and, second, the fact that they are likely also to be more or less deficient in the faculty of construction. The first of these disabilities may tend to disappear if ever the feminist movement shall achieve its ultimate victory; and the second may depart also whenever women submit themselves to the severe discipline which has compelled men to be more or less logical.”

—Brander Matthews, “Women Dramatists,” A Book About the Theater (1916)

In 2002, I was working as an arts analyst in the theatre program at the New York State Council on the Arts, where, in partnership with Suzanne Bennett, I had recently completed a three-year study on the status of women in theatre which generated a widely read report. Encouraged by my interest in the subject, two visionary directors, Gwynn MacDonald and Mallory Catlett, approached me to fund “The First Hundred Years: The Professional Female Playwright,” a remarkable yearlong citywide staged readings series directed by an eclectic group of directors, complemented by symposia involving a slate of distinguished scholars. I heard for the first time the names Elizabeth Cary, Margaret Cavendish, Joanna Baillie, Elizabeth Inchbald, Hannah Cowley, and many others. This was the beginning of my education about the Other Canon: some good, some great, some successful in their time, some way ahead of their time, all almost erased from history and the repertory.

While the previous years had awakened me to the many talented contemporary female playwrights whose work is underrepresented on the main stages of American theatre, the ensuing years would correct a long miseducation in dramatic literature and theatre history.

In three years of classes in theatre history and dramatic literature, we studied the work of few living female playwrights and read only two plays by dead ones. Scan the index of a theatre history textbook published more than 10 years ago, you might find Lillian Hellman. Perhaps Lorraine Hansberry. If it’s a serious textbook, possibly Aphra Behn and Hrotsvitha. Surely any worthy plays by women would have endured—and I would have known about them.

Learning how great was my ignorance was both humbling and infuriating. All these years I could have been reading, teaching, programming this material! Moreover, here were the shoulders on which today’s female playwrights stood—or might, if they knew of their foremothers. The restoration of women to theatre history and to the living repertory is inseparable from advocacy for living female playwrights.

At New York University, I designed a course surveying female playwrights from the 10th century to the 20th. Progress was bird by bird. Actresses started using material from class for auditions, provoking queries about the source material. I spoke on panels and presented at conferences, bringing together scholars and practitioners. Tantalized by the prospect of this hidden legacy, but at a loss as to where to begin, people started asking me for a list.

These interactions led to many imaginative initiatives. One of my NYU students, Lillian Rodriguez, along with her colleague Andrea Lepcio, invited me to cofound a series of staged readings, “On Her Shoulders,” hosted by the New School of Drama. I curated the first season. NewShoe, a collective of playwrights, invited my participation in the development of response plays inspired by the work of their foremothers. I advised “History Matters: Back to the Future,” which featured Kathleen Chalfant, Tamara Tunie, and Mary Ann Plunkett in scenes by award-winning early 20th-century women during the 2012 Association for Theatre in Higher Education conference in D.C.; the house sold out. Their educational initiative, “One Play at a Time,” invites teachers to add one new classic play by a woman to their syllabi. And the Judith Barlow Prize, which honors the anthologist of the two volumes (still in print) that first acquainted many of us with plays by women, is given annually to a student who writes an original play in response to a classic. Smaller theatres like the Halcyon in Chicago are producing more plays by women past and present, and its artistic director, Tony Adams, has become an outspoken advocate.

All this is encouraging. But with significant exceptions—New York City’s Mint Theater, Oregon Shakespeare Festival—most regionals and classical-focused theatres have made no progress on this front. In New York, three major classic theatres together produced 132 plays in the last 10 seasons; four were by women, all 20th century—and a fifth was an adaptation of a novel by a Restoration playwright. Many think they are “off the hook”—that gender parity is a non-issue when dealing with pre-modern material. Is this due to a lack of knowledge, a lack of estimation, or a lack of interest?

When we are trained to read through the filter of a canonic imprimatur, it’s a self-fulfilling prophecy. Would we think Waiting for Godot or The Crucible or Miss Julie were great if we had not been guided by that expectation? Have we not had our fill of well-trod masterpieces? Don’t we crave a more expansive repertory? Are we not curious, at least, about how the other half lived?

This list is not comprehensive. It hardly makes a dent in the wealth of material. But perhaps it is useful as a primer or point of entry. I wish it could demonstrate as powerfully and irrefutably as did the the Kilroys’ List: This work exists. Deal with it.

Essentially, I’m sharing the syllabus for my survey course; I’ve intentionally left off material that is of more historic than theatrical interest, as well as a great deal of supporting discussion. I restricted myself to plays in English.

My objective is to indicate the breadth of women, and to whet the appetites of others as mine was. My fond hope is that some of these plays will become so familiar that Elizabeth LeCompte and Ivo van Hove—not to mention interpreters yet unknown—want to mess with them.

-

Hrotsvitha Hrotsvitha (c. 930–c. 1002), the first known playwright since antiquity

Dulcitius (late 10th century)

Paphnutius (late 10th century), later adapted to Thais - Abbess Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179)

Ordo Virtutum (c.1151) - Elizabeth Cary (1585–1639)

Tragedy of Mariam (1602–1604, published 1613) - Margaret Cavendish (1661–1717)

Bell in Campo (1662)

Convent of Pleasure (1668) - Aphra Behn (1640–1689)

The Rover, Parts One & Two (1677 and 1681)

The Lucky Chance (1686) - Mary Pix (1666–1709)

The Spanish Wives (1696) - Hannah Cowley (1743–1809)

The Belle’s Strategem (1780) - Elizabeth Inchbald (1753–1821)

I’ll Tell You What (1785) - Frances Burney (1776–1828)

The Witlings (1789) - Joanna Baillie (1762-1851)

De Monfort (1798) - Anna Cora Mowatt Ritchie (1819–1870)

Fashion (1845) - Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811–1896)

The Christian Slave (1855) -

Edith Wharton Edith Wharton (1862–1937)

House of Mirth, adapted from Wharton’s novel by Wharton and Clyde Fitch (1906)

NOTE: In 1998, the Mint’s Jonathan Bank did an excellent adaptation, published in Worthy but Neglected: Plays of the Mint Theater Company. - Elizabeth Robins (1862–1952)

Votes for Women (1907) - Cicely Hamilton (1872–1952)

Diana of Dobson’s (1908)

How the Vote Was Won: A Play in One Act (1910), cowritten with Christopher St. John - Rachel Crothers (1878–1958)

A Man’s World (1909)

A Little Journey (1919)

NOTE: Though A Little Journey was nominated for the Pulitzer in 1918, it was quite forgotten until Jackson Gay directed a splendid production of this strange, almost expressionist play at the Mint in 2011. - Lady Augusta Gregory (1852–1932)

Grania (1912) - Githa Sowerby (1876–1970)

Rutherford and Son (1912) - Susan Glaspell (1876–1948)

Trifles (1916)

The Inheritors (1921)

The Verge (1921) - Angelina Weld Grimke (1880–1958)

Rachel (1916) - Zona Gale (1874–1938)

Miss Lulu Bett (1920) - Georgia Douglas Johnson (1880–1966)

A Sunday Morning in the South (1925)

Blue Blood (1926)

Safe (1929) - Mae West (1893–1980)

Sex (1926)

NOTE: In 1999, Elyse Singer directed a delightful production of the play for Hourglass Theater. - Maurine Dallas Watkins (1896–1969)

Chicago (1926)

So Help Me God (1929) - Edna Ferber (1885–1968),

with George S. Kaufman

The Royal Family (1927)

Dinner at Eight (1932) - Eulalie Spence (1894–1981)

Undertow (1927)

Sophie Treadwell - Sophie Treadwell (1885–1970)

Machinal (1928)

NOTE: The Roundabout produced the play two seasons ago, and it’s slated for Echo Theatre in Dallas next year. - Marita Bonner (1899–1971)

The Purple Flower (1928) - May Miller (1899–1995)

Stragglers in the Dust (1930) - Hallie Flanagan (1889–1969)

Can You Hear Their Voices? (1931) - Dawn Powell (1896–1965)

Walking Down Broadway (1931) - Lillian Hellman (1905–1984)

The Children’s Hour (1934)

The Little Foxes (1939) - Teresa Deevy (1894–1963)

Katie Roche (1936)

NOTE: New York’s Mint Theater revived three of Deevy’s works in the past five years, including Katie Roche, Wife to James Whelan, and Temporal Powers. - Gertrude Stein (1874–1946)

Three Sisters Who Are Not Sisters (1943)

Mother of Us All (1947) - Rose Franken (1895–1988)

Soldier’s Wife (1945) - Daphne de Maurier (1907–1989)

The Years Between (1946) - Martha Gellhorn (1908–1998) and Virginia Cowles (1912–1983)

Love Goes to Press (1946) - Carson McCullers (1917–1967)

Member of the Wedding (1950) - Alice Childress (1920–1967)

Trouble in Mind (1955)

Wedding Band (1962) - Shelagh Delaney (1939–)

A Taste of Honey (1958) -

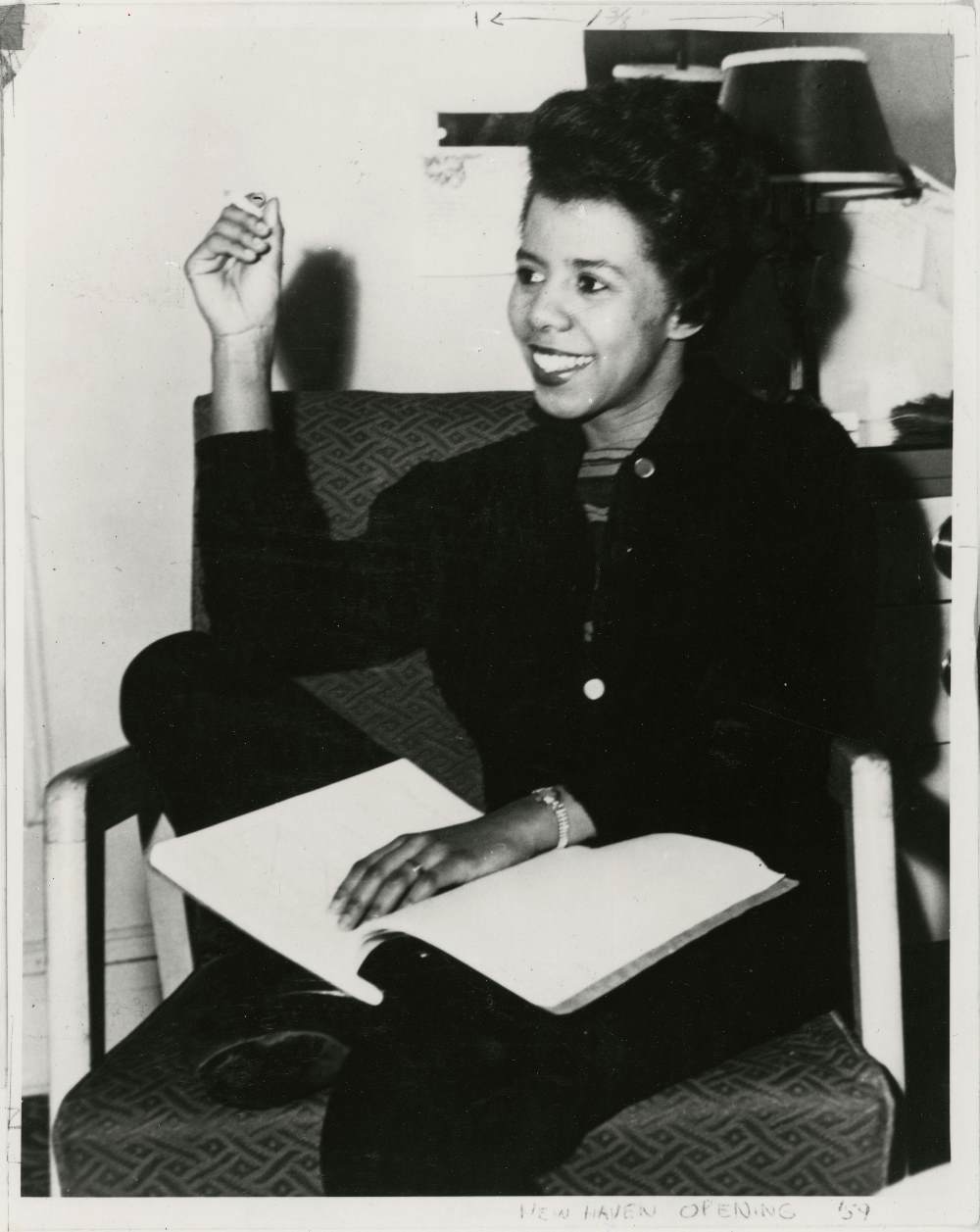

Lorraine Hansberry Lorraine Hansberry (1930–1965)

A Raisin in the Sun (1959)

Les Blancs (written before her death in 1965, first produced in 1970) - Adrienne Kennedy (1931–)

Funnyhouse of the Negro (1964) - María Irene Fornés (1930–)

Fefu and her Friends (1977)

Abingdon Square (1987)

And What of the Night? (1999)

Susan Jonas is a dramaturg, playwright, producer, and teacher who consults with foundations, service organization, theatres and schools. She is currently editing a textbook for a survey course on female playwrights over 10 centuries.