“Guys, buckle up—it’s gonna be a bumpy ride!” said director Rachel Chavkin during a rehearsal in June. She was leading a cast at New York City’s Lincoln Center Theater through Preludes, a show she cocreated with frequent collaborator Dave Malloy. This metatheatrical exploration of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s famed writer’s block and foray into hypnotherapy, with a score by Malloy mixing electronic dance music with classical, was in its second full week of previews, and Malloy had brought in new pages which required leading actor Gabriel Ebert to learn a new song on the piano before that night’s performance.

If you didn’t know the setting or subject, you probably wouldn’t guess it from Mimi Lien’s cluttered set: a pile of furniture, a piano at centerstage on a turntable, a modern kitchen with a coffeemaker occupying stage right. But that’s Rule No. 1 with a Chavkin production: Don’t expect the obvious. As Malloy said, observing rehearsal from the seats, “It could have included a psychiatrist’s office and slide-in piano, but Rachel and I weren’t interested in the literal representation of the play. We wanted to show that the music is from 1900 and 2015.”

A similar anachronistic formula propelled Chavkin and Malloy’s previous collaboration, the War and Peace–inspired epic Natasha, Pierre and the Great Comet of 1812 (which ran at Ars Nova in late 2012 before having two Off-Broadway commercial runs in 2013). The two received an Obie for their work, and the musical garmered near-universal acclaim, especially for its immersive staging, inspired by a Russian supper club, with actors performing in all directions and running through the audience, while viewers (seated at café tables) were served a three-course feast and vodka shots.

“I’m just not interested in making stuff that people already know,” Chavkin said of her aesthetic in an interview. “It goes back to the extraordinary. I think if people feel like they’re watching something extraordinary and singular, that feels live, and feels like it’s actually made up before your eyes, then a communal sense of the miracle is created. So I don’t like faking things.”

She’ll have a lot more chance to not fake things, as her career since Great Comet has exploded. This season alone she’s directing Iphigenia in Aulis, in a new adaptation by Anne Washburn at Classic Stage Company (Sept. 10–27, 2015); a restaged version of Great Comet at American Repertory Theater (Dec. 6, 2015–Jan. 3, 2016); The Royale by Marco Ramirez at Lincoln Center Theater (Feb. 11–May 1, 2016); and Hadestown, a folk opera she’s been developing with folk singer/songwriter Anaïs Mitchell, at New York Theatre Workshop (May–June 2016). That’s not even including the work she is doing with the TEAM, the ensemble she cofounded more than 10 years ago, and is still the artistic director of. The group’s latest hit show, RoosevElvis, is on tour this season.

It’s a diverse slate of work, but what may unite it all is a distinctively multisensory sensibility. Preludes, for instance, had a more traditional proscenium configuration than Great Comet, but it also contained plenty of smoke, LED lights, and, at one point, a tossed-around glow ball. When she staged Meg Miroshnik’s The Fairytale Lives of Russian Girls at Yale Repertory Theatre, she included a live female punk band; her work with the TEAM routinely blends text, video, and pervasive sound design.

“She can squeeze a lot into a small space, and yet it feels epic and sprawling,” said Ars Nova artistic director Jason Eagan. “It’s the kind of theatre I get really excited about—that lean-forward-on-the-edge-of-your-seat theatre, rather than sit-back-and-relax. She’s able to engage people in that way; there’s an energy in the room.”

High energy and a sense of physicality were evident at the Preludes rehearsal. Chavkin is not the type of director to sit stoically behind a table; she’s more likely to be onstage, getting onto her knees to demonstrate a piece of blocking, or climbing over seats into the next row for a better look. At one moment, she danced along to one of Malloy’s synth-backed tracks.

For Malloy, who met Chavkin in 2008, a typical day of work includes him giving her a script with no stage directions, and her developing staging with the actors. (In addition to Great Comet and Preludes, the two also collaborated on Three Pianos, which also won them both Obies.)

“She’s my sounding board, and a person who’s really focusing on the emotional arcs of the characters, the emotional arc of the play in general,” said Malloy. “Whereas I’m more focused on the minutiae of this kick drum sample and this string patch.”

Like the work that she oversees, the multitalented 34-year-old defies description; TEAM cofounder Kristen Sieh uses the term “master,” while playwright Bess Wohl calls Chavkin a “comet.” Those are also apt words for the trajectory of her career, which has reached beyond the confines of New York’s experimental theatre scene. Like another downtown-bred auteur, Alex Timbers, Chavkin crosses back and forth between experimental and mainstream, plays and musicals; she can bring the playfulness and adventurousness of downtown theatre to uptown and regional stages.

In person, sitting down at a midtown café for an interview, the dark-haired Chavkin speaks with a probing intelligence, and an intense self-awareness that borders on intimidating (until she lets out the occasional “fuck” for emphasis). As an only child growing up in Washington, D.C., she was exposed to both theatre and politics at an early age.

“My family is either communist or socialist, and both my parents are civil rights lawyers,” she said over an avocado sandwich (Chavkin’s a vegetarian). “My grandfather would do Clifford Odets plays in the yard of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers Union up in the Bronx, which is where he grew up. So my family is very, very political, and big believers in art as an agent for social change, and theatre in particular as an agent for social change.”

Chavkin studied directing at NYU, and during her freshman year, she saw the Wooster Group’s production of House/Lights, its infamous mashup of Gertrude Stein and ’60s grindhouse. It was her first exposure to the avant-garde. “I had no idea what I was watching, honestly, and I’d never seen anything like it,” she recalled.

She’d caught the bug, ravenously consuming shows from Elevator Repair Service, Radiohole, and SITI Company, ushering and seeing theatre five to six nights a week (a viewing habit she retains to this day when she’s not in previews). The model for the TEAM may have come from these ensembles, but the troupe’s foundation began earlier, at NYU, when Chavkin started writing.

“I was really ornery, and was like, ‘There aren’t any plays I want to direct.’ So I decided to take Allen Ginsberg’s ‘Howl’ and adapt it into a piece, and did all this research on bebop jazz. That piece ended up being very, very physical; I was really into post-modern dance at the time.”

She later served as Anne Bogart’s assistant director and received an MFA in directing from Columbia. Then, in 2004, Chavkin decided to take two shows she was cocreating to the Edinburgh Fringe. But she needed a company to do it, so she founded the TEAM with the five NYU alumni involved in those shows. Their initial fundraising efforts were something like Kickstarter before there was a Kickstarter.

“We literally wrote every person we knew who had $20 or more and asked for money,” she recalled. One of the shows, Give Up! Start Over! (in the darkest of times I look to Richard Nixon for hope), won the Fringe First in 2005. If ever there was a sign to continue as a company, that was it.

Sieh, who also plays Iphigenia at CSC, met Chavkin on their first day at NYU; they were both 17. She says the TEAM was borne “mostly from Rachel’s ambition to have her work seen. Which was great, because I don’t think any of us at the time was thinking about those kinds of outlets for art-making.”

Ten years and nine shows later, the company has expanded to 14 members, one full-time producing director, and a part-time general manager. On top of her work as artistic director (and deviser), Chavkin also oversees day-to-day operations and the grant-writing. The 2015–16 budget is $340,000. All the TEAM shows have toured nationally and internationally.

Though the full name behind the troupe’s acronym—Theatre of the Emerging American Moment—has since been quietly retired, it’s consistent with the TEAM’s focus on questioning American iconography and values, whether with a musical exploration of Las Vegas and capitalism in Mission Drift or by tumbling Scarlett O’Hara and Hurricane Katrina together into Architecting.

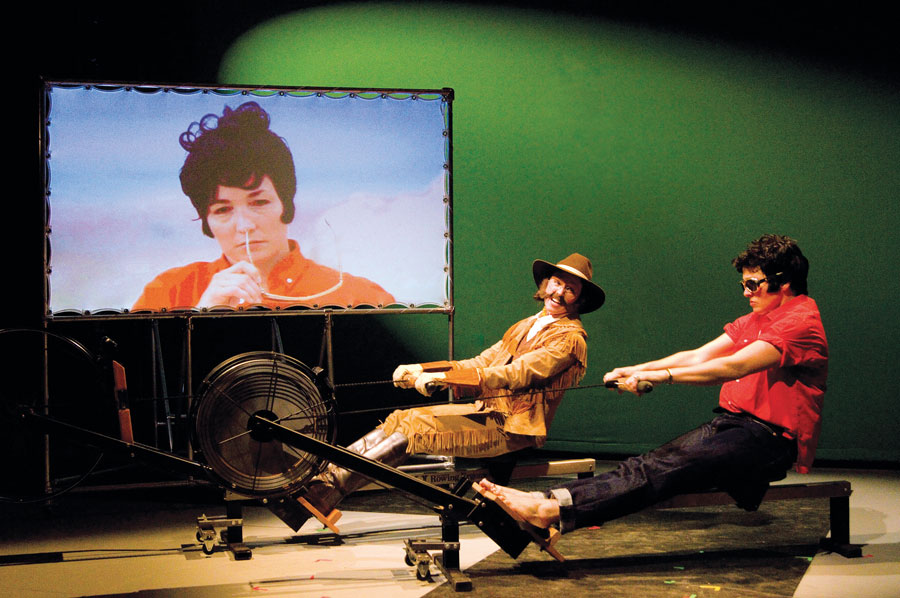

The latest American heroes to get the TEAM treatment were Teddy Roosevelt and Elvis Presley in RoosevElvis, which imagines a meeting between the two figures in the mind of a genderqueer individual named Ann, who’s struggling to come to terms with their own identity. The two-person piece stars TEAM members Sieh and Libby King, who open the play in male drag. The development process for RoosevElvis included a weeklong road trip from Mount Rushmore to Graceland, and scenes filmed en route are projected during the show.

The creation of the RoosevElvis text included a fair amount of improvisations with the two actresses in character, and then a series of revisions, arguments, group exercises, and more revisions—a process Chavkin described as “exhausting and beautiful and exhausting.” It premiered at the Bushwick Starr in Brooklyn in 2013. This season, RoosevElvis goes to the Royal Court in London (Oct. 21–Nov. 14), Walker Art Center in Minneapolis (Jan. 7–9, 2016), and ART (May 6–29, 2016).

RoosevElvis, like any TEAM show, is a dense experience, and what Chavkin wants audiences to glean from it is similarly multilayered.

“For us, and for me, it was about wanting the audience to be able to live with Ann’s metabolism, wanting the audience to know more about these two men, wanting the audience to think about gender binaries, and who gets to be a somebody and who is a nobody,” Chavkin enumerated. “And thinking about meat and appetite and ambition—whether you need to have ambition in order to have that sense of God-given right that both Elvis and Teddy have.”

Sieh, who has a busy acting career outside of the company, admits that the “best work I’ve ever done has been with the TEAM. There’s something about the process and the room we’ve built together, and the way that Rachel works, that really gets stuff out of the performer’s gut. It’s not like you go home, look at the script, and make decisions and come back having solved it. Rachel will really just be like, ‘What are you thinking? What if we did this? What if the character were to do a dance that feels like this?’ It’s a lot of provocation.”

This sense of collaboration is not just present in TEAM shows; it’s prevalent in all of Chavkin’s freelance directing work. For Small Mouth Sounds, which had a sold-out run this past spring at Ars Nova, playwright Bess Wohl appreciated Chavkin’s openness. The play, about six individuals on a silent retreat, has almost no dialogue, just a few key monologues. During tech, Wohl wondered if she should cut a monologue—a move she had considered for years.

“You can tell that Rachel thought that was a really bad idea,” Wohl recalled. “She tried to talk me out of it gently and I kept saying, ‘I just have to see this play without this in it.’” Chavkin allowed it, but the director’s instincts had been right: In Wohl’s words, the run-through “was terrible.” It was also educational, Wohl said. “A lot of directors wouldn’t have been willing to try something they knew wasn’t going to work with such open-hearted commitment. I think Rachel has that confidence where she can really explore something, and let you learn on your own what the answer is, even if she secretly knows.”

As with Great Comet, Small Mouth Sounds was staged as an environmental experience, with the audience entering a wood-paneled room filled with the sound of rain. Projections of rainfall were seen through the windows. The audience sat in halves on opposite sides of the room facing each other, while the actors performed in the center and in the far end of the room. The staging idea was Chavkin’s—the play was originally written as a proscenium play, set in multiple locations, but her avenue staging managed to convey the sense of a great hall, cabins, woods, and a lake with lighting, sound, and body language. Multiple theatres have expressed interest in staging the show, but, Wohl confesses, “Rachel put such a profound imprint on this play with her work and her contribution—I’m curious but also terrified to see anybody else tackle it.”

Despite her numerous forays into immersion, there is no such thing as a typical Chavkin show, or even a style. Her work is driven by a sense of the holistic, of the body and all of its senses, and a need to intellectually and emotionally engage both artists and audiences.

“The way I tend to think about plays is: My job is to create a culture that can produce the events of that play,” she explained. “So for each play, the culture is going to be different, and that culture includes how we speak and how we move. It includes how time functions, what furniture there is, and whether costumes are contemporary or classical. The audience has to be a part of that culture, because otherwise they won’t get it, they won’t feel it. That doesn’t mean they have to be inside of it, but it means they have to be part of it—meaning they have to feel it in their bones.”