About two years ago, I wrote a sequel to my 1989 comedy, Lend Me a Tenor, and called it A Comedy of Tenors. It’s about to receive its world premiere in a coproduction of the Cleveland Play House and the McCarter Theatre Center, two terrific and, in this case, intrepid theatres.

I have to confess that I’m not fond of the word “sequel.” It sounds rather premeditated, like something slithery about to strike. But I went ahead and wrote the sequel anyway because I’d become rather partial to the band of loonies in Lend Me a Tenor, and I thought it might be fun revisiting them these many years later. It has, in fact, been a joy. Whether the audience feels the same way remains to be seen.

I never dreamed of writing a sequel until four years ago when Lend Me a Tenor had a Broadway revival. As I sat in the audience, I could see how much the people around me enjoyed being in the company of my old friends from the Cleveland Grand Opera Company, and I was reminded how much I liked them myself. Then one night I had a thought:

What if I wrote a play about these characters two years after the end of Lend Me a Tenor? Where would Max—dogsbody and aspiring opera star—be? Would he be singing for a living? Would Max and his girlfriend Maggie be married? What about world-famous opera star Tito Merelli and his wildcat wife Maria? Would they still be together?

The one rule I knew I wanted to follow was that the two plays should be independent and that you wouldn’t have to see Lend Me a Tenor in order to understand or enjoy A Comedy of Tenors. After that, all bets were off.

Typically, when I get an idea for a new play, I start thinking about how other playwrights have handled the same idea (there’s nothing new under the sun, I suppose), and I started thinking about the whole concept of a sequel. Were there any really good ones back there in the history of drama?

Many of my favorite plays bear the distinctive marks of their comic creators. For example, Sheridan’s 18th century The School for Scandal is clearly a kissing cousin of his early comic masterpiece The Rivals; but none of my favorite comedies fit the real sequel category. The Merry Wives of Windsor? It contains several of the characters in Henry IV, Parts 1 & 2, but it’s really more about Falstaff in love than a continuation of the histories.

In a way, the dearth of sequels in the theatre is rather surprising. The urge to see our favorite characters for a second or third time is a natural one, and we see this urge satisfied time and again in movies and television, and of course in books. In the 1930s, the movie The Thin Man was an instant hit, and it was followed immediately by five sequels. In television it’s a commonplace. How many millions of us have loved following the Dowager Countess, played by Maggie Smith, in Downton Abbey over the years? Almost all of television is sequels—they call ’em episodes—to say nothing of books like the Jeeves and Wooster series by P.G. Wodehouse. Still with me? Right ho.

So: loads of sequels in other art forms, almost none in the theatre. But there is one whopping exception, and it was written by the stunningly named Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais. Beaumarchais wrote The Barber of Seville in 1773; then a few years later he wrote The Marriage of Figaro using four of the major characters from the earlier play and setting it three years later in time. Both plays are masterpieces, and they were both made into the best comic operas this side of paradise.

What’s really interesting is that while The Marriage of Figaro is just as hilarious as Barber, it has an entirely different tone. It asks some serious questions about marriage and politics, and it brings the lives of its characters full circle. These two plays encouraged me to forge ahead, and to try it in a similar way.

In writing what I was by now calling Tenor Two, I started thinking about my daily life as a writer and how we so-called artists sometimes have a heck of a time balancing the conflict between art and life. Put this way, it sounds rather highfalutin’, but there it is.

I have two monstrous things called children, a girl and a boy, and there are times when I’m in production for a new play, a continent away, sitting in a theatre for days at a time, when I wonder how badly I’m shortchanging the little creatures. This question set off a few bells as I scribbled my way through A Comedy of Tenors.

In the play, superstar Tito Merelli has been married for 25 years, all the while spending weeks at a time performing on the road. How does his wildly demonstrative wife Maria put up with it? And how has it affected his glamorous young actress daughter, Mimi? Will Mimi end up marrying a fellow artist herself? And if so, will that put her in conflict with her artist father?

These questions make things sound terribly more serious than the play is meant to be. But exploring these characters a bit more deeply while keeping them buoyant and funny (Oh Lord, I hope so) felt pretty wonderful.

When I turned to writing the play itself, the plot came surprisingly quickly, partly because I based it on an historical event. In 1990, a music producer came up with a pretty wild idea: He would stage a charity concert starring the three greatest tenors in the world—Luciano Pavarotti, Placido Domingo, and José Carreras—and he would present it at the Baths of Caracalla in Rome on the eve of the World Cup soccer finals. He called it “The Three Tenors,” and it turned out to be the classical concert of the century. To this day, the album is the bestselling classical album of all time, and the follow-up concert (the sequel, if you will) was watched by more than 1.3 billion viewers on international television.

So my premise was this: Henry Saunders, the wily producer of the Cleveland Grand Opera Company from Lend Me a Tenor, has come up with the same idea—only 50 years earlier, in 1936. He’s staging a concert in Paris called “The Three Tenors” starring Max, Tito, and a rising superstar named Carlo Nucci—and he’s doing it at a soccer stadium which happens to be located next to one of the finest hotels in Paris, where the action of the play unfolds.

After that, the plot was simplicity itself. Tito is having a midlife crisis. Max and Maggie are having a baby. The famous Russian soprano Tatiana Racón, who is Tito’s former lover, is visiting Paris. Tito and Maria’s daughter, Mimi, is also in town with her own lover. And everything that possibly could go wrong does go wrong.

The writing of A Comedy of Tenors has turned out to be more fun than I’d ever imagined. I thought I had said goodbye to the characters in Lend Me a Tenor when the play first opened on Broadway so many years ago, but A Comedy of Tenors has allowed me to spend time again with some of my very best friends. It’s been like going to the best college reunion ever. So when’s the next one?

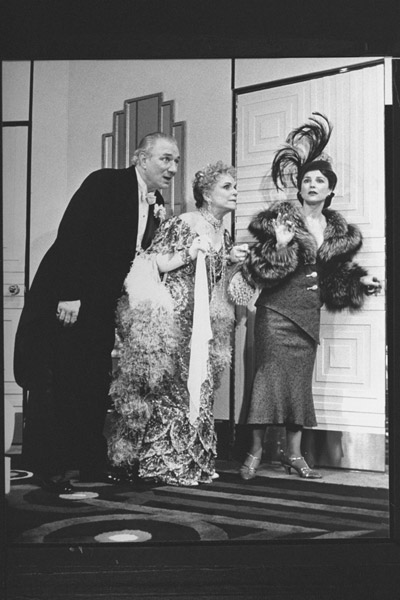

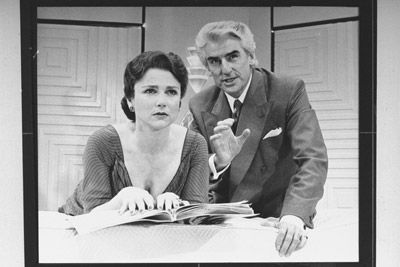

Ken Ludwig’s Lend Me a Tenor, named “one of the classic comedies of the 20th century” by The Washington Post, won two Tony Awards and was nominated for seven when it premiered on Broadway in 1989. The sequel, A Comedy of Tenors, runs at the Cleveland Playhouse through Oct. 3 and at McCarter Theatre Center Oct 13–Nov 1. Follow Ken on Twitter @ken_ludwig and visit www.kenludwig.com.