“Hamilton is the single greatest source of pain in my job,” said Alison Carey, only half-jokingly, in a recent interview in her office at Oregon Shakespeare Festival. Carey runs the theatre’s ambitious American Revolutions program, a 10-year commissioning project to create a new American “history cycle” of plays from the likes of Culture Clash, Paula Vogel, Tanya Barfield, and Robert Schenkkan (whose All the Way made it to Broadway and won a Best Play Tony). I was in town to report a larger feature on the company and the eight-year-old tenure of artistic director Bill Rauch; and though I knew OSF had had nothing to do with Lin-Manuel Miranda’s current hip-hop history sensation, which is turning the original American Revolution into theatrical gold, it was only logical to mention it to Carey. Right?

When you a run an American-history-play commissioning program, it comes up a lot, apparently. Julie Felise Dubiner, Carey’s associate, said to her, “Show him the folder,” then turned to me and deadpanned, “I was going to run over and restrain her when you brought up Hamilton.”

Carey produced a folder from a hanging file behind her desk labeled with the initials “FFHHBC.”

“That’s Founding Fathers Hip-Hop Boot Camp,” she said. “When I first came here in 2007, I said, ‘We have to find someone to do hip-hop founding fathers.’ I approached some people and I had big conference calls about it, and everybody was like, ‘Well, that’s not that good an idea.’” She said she asked Universes, the hip-hop theatre trio from whom she would instead commission the Black Panthers/Young Lords–themed Party People, “‘Are you sure you don’t want to do hip-hop founding fathers?’” They were like, ‘No, thank you.’”

Why had she been so insistent, I wondered?

“Because it’s a good fuckin’ idea!” she said. “You have a group of people talking about ideas, and how do you make it exciting?” She repeated it, like a mantra: “Hip-hop founding fathers—right there, right there! I wrote this folder eight years ago.”

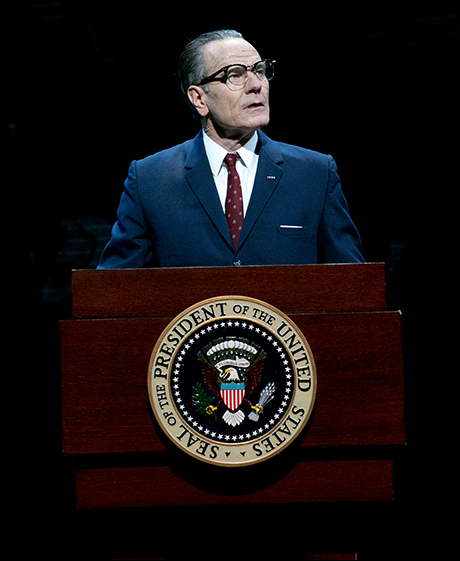

In the interim, AmRev—as it’s known for short—has commissioned 23 of its slated 37 history plays, and staged seven of them: Party People, both of Schenkkan’s LBJ plays, All the Way and The Great Society, Culture Clash’s American Night, Naomi Wallace’s The Liquid Plain, Tony Taccone’s Ghost Light, and Lynn Nottage’s current Sweat. Next season is Lisa Loomer’s Roe, about Norma McCorvey, the woman behind the epochal Supreme Court decision on abortion rights. So far one AmRev commission has popped up at another theatre—Frank Galati’s E.L. Doctorow adaptation The March, at Steppenwolf—and another, Paula Vogel and Rebecca Taichman’s Indecent, will bow at the theatre that co-commissioned it, Yale Rep, in October, in a coproduction with La Jolla Playhouse. Carey said she’s eager to see the plays go out in the world, and that, as with many theatres’ commissioning projects, it’s no reflection on their quality if they don’t make it to the OSF mainstage.

Has the history frame been constraining for Carey or the playwrights she’s commissioned? By and large, she’s kept the aperture wide and let playwrights write whatever interested them, with two caveats: Sensing lacunae, AmRev specifically sought out plays about guns in American history, about the environment, and about the African-American relationship to Civil War history, and they’re getting them from Dan O’Brien, Idris Goodwin, and Dominiue Morisseau, respectively. (And yes, Carey confirmed, to my delight: Morisseau has been in conversation with the great Ta-Nehisi Coates, whose writerly journey through Civil War history has been the definitive contemporary lens for the conflict.)

The other intervention AmRev regularly stages to prevent both homogeneity and conflict among their slate of plays is to bring all the commissioned writers together once a year, as many as can make it, in either New York or Los Angeles. Still, Carey noted, “The interesting phenomenon is that the initial plays were largely about the ’60s and ’70s. We were talking about why, and it’s obvious that those of us alive today—especially people who happened to be alive then—are still trying to figure out what the legacy of that period is. It seems like so much got broken open in terms of national identity that we’re still trying to figure out.”

Nottage’s Sweat may seem to be the least distant historically: It takes place in 2000 and 2008 in Reading, Pa., among factory workers whose jobs and lives go south in the intervening years. Nottage recently told me that she considers the post-NAFTA “de-industrial revolution” one of the great pivot points in American history: “I do think it’s going to be a moment that will impact the next 100 years.”

Carey conceded, “We originally thought, ‘Should we make a date and say this is when history ends?’” But Taccone’s Ghost Light, a memory play about Jonathan Moscone’s relationship with his late father, assassinated Frisco mayor George Moscone, was set partly in the present day, as were some of the moments in Culture Clash’s immigration-themed American Night. “Playwrights find what they need, right? And we’re good with that.” What’s more, Carey said, “We don’t want any sort of pretense at definitiveness, because that’s such an essential lie.”

Shakespeare is something of a guiding spirit here: Not only did he write just the histories that he (or his patrons) were interested in; he also clearly wrote them from his contemporary vantage point. But artistic director Rauch, who cooked up the original commissioning idea, at first had an almost hilariously methodical notion for the project: a play on each president.

“But then we thought, ‘Oh, that whole Revolutionary War was to disconnect the notion of leadership and monarchy,’” Carey said. “It seemed antithetical to the spirit of the U.S. to focus on the presidents that way.” After much discussion, she said, “We found this lens of looking at moments of change—which is, of course, not a very tight lens, because all plays are about moments of change. Except maybe Waiting for Godot. It was realizing that rather than a play for every president or every decade or every state or every amendment to the Constitution, we wanted playwrights to actually write about what they care about.”

Along the way, Lin-Manuel Miranda wasn’t the only writer who got away. Suzan-Lori Parks was initially announced as being among the comissionees, but at some point, Carey said, “She just stopped returning our calls.” It seemed especially bittersweet when her Civil War–themed Father Comes Home from the Wars (Parts 1, 2 & 3) premiered at the Public Theater, where she’s a resident playwright. Said Carey, “It was like, ‘You do know we would have just paid you for that?’ But people gotta be who they are.”

Circling back to Hamilton, she said something similar about Miranda and his Public-developed musical: “We would have just written him a check.”