I met the actors covered here (and in next month’s continuation of the story) in January 1995, when I was guest literary director at ART, and I followed them for 15 months, June to the following September, before publishing their story in three parts in the pages of this magazine. It’s been 20 years since that first journey together began and almost 30 since I began writing for American Theatre. All this writing has been done under the editorial tutelage and with the deep friendship of AT’s founding editor-in-chief Jim O’Quinn. This follow-up article appears in the last issue Jim will edit, as he retires after 33 years leading the magazine. He has pioneered a new kind of advocacy journalism and criticism, and I’m proud to have been a collaborator on the front lines of that effort. Nothing I’ve written about the theatre in these long years would have been written without Jim. I dedicate this story to him, with love and a mess of gratitude. — Todd London

“For every person whose contentment comes from faithfully executing a predetermined script, there are at least 10 if not 100 who had to rearrange the pages and play a part they hadn’t expected to, in a theatre they hadn’t envisioned.” – Frank Bruni, The New York Times

This is a story about time, its passage, and how it shapes lives and alters ambition. It’s also a story about the lens of time, because that lens shapes the stories we tell about our lives, too.

This is a story about time, its passage, and how it shapes lives and alters ambition. It’s also a story about the lens of time, because that lens shapes the stories we tell about our lives, too.

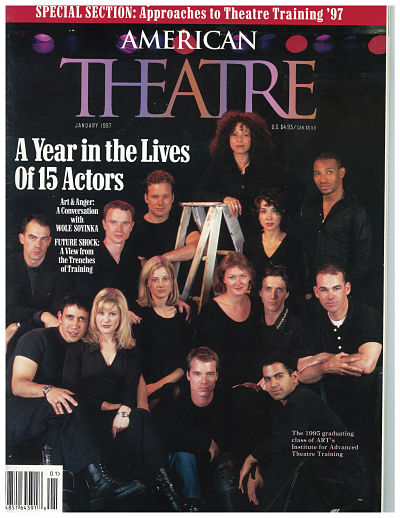

This story began 20 years ago, when its cast of 15 was made up of young actors, 23 to 33 years old, finishing two years of graduate work at the American Repertory Theatre and its Institute for Advanced Theatre Training at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass., and heading off to New York City to embark on the rest of their careers. In other words, it began in the future tense, as each of these actors imagined and prepared for life in the profession they’d chosen and for which they’d trained.

I met them then, and, after trailing them for over a year, wrote a three-part article, under the umbrella title “Open Call,” which ran in the January, February, and March 1997 issues of American Theatre. (You can find them all here.) Now, from the vantage point of their mid-40s and 50s, with all the life that happened in those intervening years, the imagined future these actors shared with me has morphed into a lived past. If graduation from ART in June 1995 was, as I wrote then, “a parting wave from the dock,” these players are well into mid-sail.

Actors are natural nomads, traveling from show to show, theatre to theatre, town to town. You’d be hard-pressed, though, to find one as peripatetic as Tom Hughes. Beirut, Rome, São Paulo, Melbourne, Abu Dhabi, you name it—his work has taken him there. And he’s moved his family with him, from New York to Utah and back, to Connecticut, North Carolina, Southern California.

Hughes hasn’t traveled the world as an actor, though, but in business class—first as an organizational psychologist and trainer for Booz Allen Hamilton, then for Duke Corporate Education, alternating with stints as a self-employed worker on contract. “This is the craziest life,” Kristen, his wife of 20 years, says. “We just get yanked and yanked around.” All in the name of stability.

This was not the plan. The plan was to act. In New York City, where I last saw Tom and Kristen in 1996, they were living in a sublet near Lincoln Center, later in a $680-a-month two-bedroom apartment at 181st Street. They were $50,000 in debt from school. Their first son, Steven, was born that November, just as my series of articles about Tom and his classmates went to press. Tom was going to stay home with the baby, audition, and continue to write books and short films based on Bible stories, as well as an interactive CD-ROM (remember those?) for his church. Kristen would teach. During summers, Tom would act while Kristen stayed home. But Steven’s short stint as a baby-foot model for Parenting magazine was about as close to professional careers as they got.

Soon Kristen discovered that she wanted to be the parent on the ground, so Tom, on an 11th-hour tip from a friend, applied to an organizational psychology master’s degree program at Columbia University Teachers College. With no relevant background or experience (but Ivy League cred), he was accepted into the program. Three semesters later, he had his degree and the assurance that he was at the “front of the curve” for hiring at one of the “big eight” consulting firms. Presumably because of his lack of experience, months went by. No job. In the meantime he did some acting and writing, including making a number of films for the church, in which he played some of the apostles and “Jesus twice.” Just when the threesome had packed up their NYC apartment to move to Utah, a call came from the prominent Booz Allen with a job audition (consulting firms don’t call it that, though) in Brazil.

Tom had interviewed months before, still sporting a full Jesus beard. Now he showed up clean-shaven to lead a sample workshop on “the ladder of inference” in São Paulo. They didn’t recognize him. Again he heard nothing for months.

Finally, nine months after his first interview with Booz Allen, they offered him a post back in New York, starting Nov. 1, 1999. Tom lived in hotels and looked (with no luck) for a two-bedroom in their old neighborhoods of Inwood and Washington Heights. When Kristen joined him, they moved into an unsellable model house in Connecticut, acting, Stepford-style, as the model couple to help sell the house. Six months later they were looking again. Meanwhile, Tom traveled the world.

One day they were picking through the pockets of Kristen’s coats, looking for $1.50 to get her to work at the Manhattan Episcopal preschool where she taught; the next Tom was calling from the Champs-Élysées in Paris, just before the millennial New Year, snow falling around him, to ask, “How did this happen?” Their daughter Carrie was born the following September and, with Tom away for weeks at a time (the kind of away that went on for years), Kristen began to learn “how to be a happily married single mother.”

By 2002 Tom’s work was taking him more and more back to Utah, so his boss encouraged him to base himself there. They bought a beautiful house in the foothills of the Rockies. But the travel got worse. He could find his way around Rome or London, but, as he discovered one day, he didn’t know how to find his son’s school in their Utah town of 5,000 households.

While Tom Hughes’s path leapt oceans and led him far afield, Randall Jaynes, who had, since his earliest days, imagined himself as a traveling repertory actor “with my little hobo bag,” has stayed firmly rooted. He arrived in New York in 1995, got hired by Blue Man Group the same year, and never left. “Still with Blue Man. Still strong here,” he tells me when we Skype between my home in Seattle and his in Brooklyn, using a technology that would have seemed strictly sci-fi when last we met.

Randall was one of the first generation of replacements for the three musicians/performance artists/clowns who founded the international phenomenon—in ’95 he became, by his reckoning, the fifth Blue Man. A few years later, as a performer/director, he became part of the troupe’s infrastructure, performing all the time and creating new shows. Currently he’s director of performer development, part of the team that hires and trains every Blue Man. “I caretake the character—getting to it and straying from it and pushing boundaries.”

And while he’s moved only a subway stop away from the BMG-owned apartment in the East Village he shared with ART classmate Kevin Waldron in ’95, in his role as character director, he visits every one of the nine venues Blue Man occupies. He sees the show in every city at least once a year, which a couple of seasons ago meant 18 trips. He runs workshops for the 70 or so performers, and often blues up with his latex gloves and prosthetically bald blue head to join the show. It’s “like being a teacher—that’s the part I really love.”

He also loves the creative development, inventing new stuff for the show, as the Blue Men crack each other up, literally and figuratively dropping their pants and throwing water or whatever else they have at hand. “Our little subculture within the company remains monkeys throwing mud at each other…that’s our role in the village. Everyone cares very deeply about the spirit behind the whole piece, the investigation of what it is to be alive, what it is to connect to other people. That’s a real theme. It’s not a bullshit thing.” Randall and his crowd are highly skilled professional people, serious and passionate about play.

Randall’s life may appear diametrically opposite to that of Tom Hughes, right down to the difference between the Blue Man getup and international businessman drag. Both, though, have put family before creative fulfillment. Tom left the theatre behind once his children were born. When I ask Tom and Kristen how it feels to have done so, his answer is concise: “Hurts.” In a less drastic fashion, Randall put his own creative projects mostly on hold after his son Dashell was born in 2004 and again when his daughter India was born five years later.

One of the values of Blue Man Group is the creative support of its members, and, in his early years there, Randall enjoyed a fertile time as a creator/performer of his own work, some of which toured internationally with other members of his ART class. The work grew out of the same long-term commitment to movement-based physical experimentation, clowning, and puppetry that made him ideal for a 20-year career in blue. He explored iconic fantasy characters like Pinocchio and the Tin Man and, in pieces like The Birdcatchers and Billy Nijinsky, blending psychological and physical experimentation. The latter piece, which he mounted in 2002, was the last time he made work outside of the context of his job. It wasn’t planned that way. Everything that wasn’t part of the job was “allocated toward my family,” he says. “I didn’t have the creative bandwidth.” Currently, though, he’s happy to be developing a new piece with the troupe’s artistic director out of the need to tell his own story, which BMG has never filled. “That yearning has always been in me.”

There’s another common thread to Tom and Randall’s divergent journeys: those twins, stress and aging. Whether you travel the world for business or stay in one place for art, whether you fly business class or leap into the air to catch marshmallows in your mouth, stress and aging can get the best of you. Tom has undergone five surgeries (two for carpal tunnel syndrome, one for a perforated appendix, and, in later years, emergency neck surgery for nerve and disc damage), possibly related to work stress. Similarly, before he began practicing kung fu seven years ago, Randall’s “health on every level was failing.” He suffered from internalized stress, a benign growth in his inner ear, a T3 spinal swelling that caused nerve pain, and viral meningitis. “I didn’t have a structure to care for myself,” he confesses. Now he and his 11-year-old son are Brown Belt Twos together. He’s found some balance.

Still, despite Randall’s 20 years at the same job, he said, “Nothing’s ever felt that settled. Everything’s a moving target.” Partly that’s the artistic unsettling of Blue Man Group itself, which is “constantly changing and reinventing itself, like a phoenix.” Then there’s New York City itself, which, as I wrote at the time (“four decades into the alternative/regional theatre movement in America”), all 15 actors still saw as the “magnetic center of opportunity” and felt compelled to take on. Two decades later, only three remain in the city—Ajay Naidu, Mark Boyett, and Randall. But not a day goes by that Randall and his wife don’t talk about getting out, something that isn’t feasible given the round-the-clock demands of BMG. The city isn’t a “natural feeding ground” for either of them—he’s from Northern California; she’s from Georgia. And though they own their own home in Williamsburg, a “little shanty” with a front yard, “the damn city,” as he calls it, is the one constant conflict in their life. “The subway drives me nuts.”

Even roads that appear to lead inexorably away from theatre, as Tom Hughes’s does, may wind back around. After years of hiding his acting résumé to bolster his business creds, Tom now spotlights this experience through his role with a group in Mill Valley, Calif., called Stand & Deliver, where he works alongside actors, directors, and theatre educators to lead “high-performance communication training” for business professionals from around the world. Might it be true that an actor’s training is never entirely lost, never entirely wasted?

Nothing, it seems, has been lost on Siobhan Brown. Her 20-year trail is an object lesson in using everything, reclaiming everything—even, in the most profound way, a Native language.

April 11, 2015, the day after I spoke with her, was the celebration of the Commonwealth Shakespeare Company’s 20th anniversary season. That theatre, founded by another ART alum, Steven Maler, performs free Shakespeare on the Boston Common. In 1996, as Siobhan’s first year out of school ended, she kicked off CSC’s first summer as Titania in A Midsummer Night’s Dream in Copley Square. She played Romeo and Juliet’s Lady Capulet in Year Two and Olivia in Twelfth Night the following season. As recently as 2012 she returned, in All’s Well That Ends Well. In about 24 hours, she would reprise her first role as the Fairy Queen, coming full circle. At the end of that circle: Siobhan herself.

Starting in New York, Siobhan—whose heritage blends Native American, African American, and Mexican—was initially sent up for specifically African-American roles in contemporary plays. Over time she landed more classical parts, including a tour with the Acting Company where she played a role that would prove prescient her life in ways she could never have expected. While Siobhan had always “embraced being Mashpee Wampanoag” and been active in her culture, her performance as Ramona Bennett in Peter Frisch’s adaptation of Studs Terkel’s American Dreams: Lost and Found became a touchstone. She would replay the words of this Puyallup woman far into the future, even as her own work life transformed.

In 2004 Siobhan returned home to Massachusetts. It wasn’t the end of her career in theatre, but part of letting go of acting as “the primary source of my hustle.” She never left the theatre entirely—“Whenever I try to step away, I get pulled back in—it’s like the Mob.” It isn’t the Mafia tugging, though, but the “really, really beautiful communities” she’s formed, including at ART. After she’d worked outside the arts for a year and a half, Commonwealth’s Maler called again, looking for a teaching artist. Siobhan stayed at the Wang Theatre/Citi Performing Arts Center for seven years, eventually becoming manager of performance programs, then associate director of education. “It was a good combination of a lot of things I’d been working on unknowingly” doing “admin” jobs to make rent in New York.

Siobhan was instrumental in starting the City Spotlights Leadership Program for area teenagers, which involved forming neighborhood ensembles. From there, she became interim director of the school program at Actors’ Shakespeare Project, started 10 years earlier by friends from ART and Emerson College, two of her “beautiful communities.” From that perch she combined her organizational and educational work with her classical training and love of Shakespeare, partnering with a Boston foundation called Edvestors, which funds partnerships among artists, arts organizations, and schools “to make sure that every student in BPS has arts instruction of some kind from kindergarten through high school,” as Siobhan puts it.

In the summer of 2013, Siobhan had the opportunity to teach with the Native Tribal Scholars program. She took it. The program, housed for the summer at the University of Massachusetts–Amherst, was intended “to curb the high school dropout rate” (which stands at about 50 percent) among Native American youth and prepare them for college. Siobhan did Romeo and Juliet with the kids, who decided to set the play in tribal communities. Families were of “similar but rival tribes—the ball was actually a powwow, so it opened with the girls doing a fancy dance, a traditional dance.” Romeo consulted a local medicine woman instead of the Friar, and the characters greeted each other in their own languages. “They were really bringing those two worlds together,” Siobhan declares.

Apparently she did, too. Later that year she went to work with her cousin and friend—now her boss—Jessie Little Doe Baird, a MacArthur Fellow, on the Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project. Baird had been working to bring the dormant language back to life, more than 150 years after its last known speaker had died. The language, part of the Algonquin family, had a significant past and was the language of the first translation of the Bible on this continent. Thanks to Jessie’s work, first at MIT and then with WLRP, “we’ve been able to welcome the language back home.”

Siobhan, part of a staff of six, is currently writing a curriculum for an elementary K-3 program, “hoping to receive a charter from the state of Massachusetts.” A lot of the job is learning the language—about eight or more hours a week of immersion. Classes are free to tribal members. On the day we spoke, Siobhan had just taught a group of six preschoolers “numbers and colors and clothing—all of it with warm-ups and making funny faces and being as theatrical as possible.”

Full circle indeed. Siobhan remembers delivering Ramona’s ideas in American Dreams: Lost and Found, feeling “kind of removed from the fact that something was deeply, deeply wrong”:

The marriage between the non-Indians and the Indians was a perfect one. The Indian measures his success by his ability to share. The white man measures his importance by how much he can take. There couldn’t have been two more perfect cultures to meet, with the white people taking everything and the Indians giving everything.

“I gave this speech every night,” Siobhan reports, and questions lingered in her mind. “What am I doing about that? Am I educating myself enough about my own people? How am I helping with the healing or the growth and development of Native youth?”

It’s tricky, thinking about Siobhan and some of her classmates, to gauge how much their theatre training is still in them, even as it’s difficult to parse out whether they’re still “in the theatre.” Like Siobhan, James Farmer started out in NYC, taking jobs out of town, including in Orpheus Descending at Philadelphia’s Wilma Theater. Like Siobhan, he did a stint with the Acting Company (including Romeo and Juliet) and performed in numerous Shakespeare plays. Like her, he is now teaching. “I’m one of those people who still has his toe in,” James says of theatre. “I do it just enough so that it’s painful—it’s like a scab that never quite heals. I keep tearing it off.”

James left New York City in 2006, when his son was six years old and his daughter was two. “My kids were born and everything kind of shifted.” He’d gotten his teaching certificate from City College, saved up for a year or two, and with his wife loaded the kids into a Hyundai and camped their way across the country. “James rates adjectives like ‘burly’ and ‘strapping,’” I wrote in ’96, and the description still holds: “He appears to (and literally does) come from Steinbeck country.” This native Californian wanted the kind of outdoor life you can’t live in Manhattan. They chose Portland, Ore., a place he’d never been. “I’m glad we did,” James says. He’s found there “the best of the West and the East Coasts. There’s a higher density than in most West Coast cities. Interesting neighborhoods.”

Once in Portland, James substitute-taught, as he’d done early in his career, alternating between short teaching stints and longer ones as a stay-at-home dad. He’d left behind a job teaching English full-time at Columbia Prep on the Upper West Side of NYC. Once in Portland, though, he was able to get back to his first love—at least as a teacher. He landed a job running the theatre program at Beaverton, a big public high school west of the city. He teaches acting and design, technical theatre (“Nobody’s lost a finger yet, so…”), and ensemble work, as well as English courses and a yearlong International Baccalaureate class. He directs a play in the fall and a musical in the spring, working 68 hours a week and stealing the rest of the time with his own kids. He’s grateful that “I still get to live in the dramatic literature.”

Even though he’s trying to get used to the fact that 50 is staring him in the face, he’s eminently castable, as proved by his landing Petruchio in The Taming of the Shrew at Portland Shakespeare Project a few years ago and Levin in Anna Karenina at Portland Center Stage before that. Toe in, scab off. But Beaverton is a full-time job, “six days a week when we’re in performance.” He misses the camaraderie of the theatre—he felt instantly at home with the other actors in Portland—but his days are good. He loves directing the shows, has a solid income and some money in the bank, and has put away the beginnings of college savings for the kids. By contrast, “$13–18,000 was a good year as an actor.” Teaching’s what he calls a “sweet second choice.”

So what does he mean about the scab that never heals? “Twenty years ago we were at this elite institution. We all had our Equity cards. We were all headed to New York. And then life happens. You make choices.” He had hopes, but didn’t know what was going to happen. He imagined getting “bigger and bigger gigs, then maybe get some film roles.” He also looked up at the ART acting company and “thought that would be me.”

It worked out well for a while. “I had a kind of mid-level regional career, but it’s hard to keep a family together.” He goes on: “There are times that I’m very content in my life. I get to go home and mow my lawn. I like all that domestic crap. I like my neighborhood.”

I look across the café table at James and think about my own high school theatre teachers and their life-changing impact on me. I have no doubt that he’s making just this kind of impact on students at his own school, and that one day, 40 years on, they’ll be thinking of him with profound gratitude. At the same time, I look at this powerful, classically trained actor and wonder: How might his life have been different (and, maybe, in those deeply felt domestic ways, the same) if the regional nonprofit theatre hadn’t abandoned its commitment to professional acting companies?

CHANDLER VINTON takes me on a virtual tour of her house in Connecticut. Because she’s carrying her laptop to film the place, the screen images can become blurry and pixelated. There’s no mistaking, though: It’s a beautiful home. “This is my attic,” she says, pointing to a picture of Shakespeare on the wall, a library of shelves with theatre books, a series of binders with programs and cards. Chandler keeps thorough scrapbooks of everything she does. The first thing in the first scrapbook is a $50 check stub for a play she did at Harvard. Later there’s a program for a Bristol, Pa., production of Grigory Gorin’s Forget Herostratus!, in which she met her now-husband, David. They had a “showmance.”

She’s very organized, so my questions are answered with evidence. Chandler interned at New Dramatists in 1997, during my second year there as artistic director. For the next several years she worked as a receptionist at a company that produced commercial events for Toyota and Mercedes-Benz. She rose to office manager, jobbing five days a week from 8 in the morning till 6 at night. When they offered her a full-time position, she turned it down, saying, “No, I’m an actress.” Meanwhile, she performed in showcase productions, thesis projects, and scene nights at Columbia. She worked downtown at HERE Arts Center and Access Theater and the Flea, mostly on new plays: Charles Mee’s The Bacchae 2.1, Kate Moira Ryan’s Damage and Desire, Whale Music by Anthony Minghella.

She left the day job around 2002 and her acting career picked up, starting with a role in Heiner Müller’s Quartet at Brooklyn Academy of Music. She doesn’t need a scrapbook to recall verbatim the “worst reviews ever.” Her favorite: “‘It’s like a dumpster outside of NOBU, full of mouthwatering, delicious bits, but it’s still just garbage.’ It was,” she agrees good-humoredly. She’s got it all, including Excel files documenting her production history and every audition. She’ll send them to me—“so you can see how my career waned,” she says, upbeat.

First regional production, Jeffrey Hatcher’s Mercy in a Storm at City Theatre, 2002. Married, 2004. Spent 2006–07 in D.C. doing five plays, while her husband was in the company at the Shakespeare Theatre. Moved to Connecticut, 2008. The Price at Pittsburgh Public Theater, 2010. Last job. That’s the year she stopped keeping records.

The move to Norwalk “put the kibosh on my acting career.” Why did she move? “We wanted a house,” and her husband, who had stopped acting, wanted one in Connecticut. She’d sold her apartment in Brooklyn at the first showing, and when he took her to see the house an hour north in Norwalk, “I was thunderstruck by what I could purchase for 60 percent of the cost of what I could buy in New York!” Before long, “going into the city [to audition] was exorbitantly expensive and time-consuming. For 15 minutes in a room? I was like, ‘I don’t care.’” It was a big lifestyle change. “I just kind of drifted away from acting…unless you’re actively engaged, you’re not in it.”

She needed a paycheck, though, and, having always considered herself a “one-trick pony,” never thought she’d find something she loved like acting. She did, though: She loves plants, and there are lots of nurseries in Fairfield. Chandler staged a drive-by search of them in the dead of winter, when all were closed except one, a destination nursery that was “absolutely beautiful.” She called, and they asked for a résumé. She admitted to no experience except that of being the plant volunteer who made her Brooklyn co-op part of the award-winning “greenest block in Brooklyn.” She got hired as a sales associate in the annuals department, where she’d help unload trucks, price the merchandise, maintain the plants, and work with customers who came in with questions. She shows me the label on her shirt: “Oliver Nurseries.” She’s been there since 2009. “I don’t think I would have given up the ghost on the acting unless I’d found something I love equally.”

Two years ago she took an AutoCAD class for computer design, and last year she moved to Oliver’s landscape design office. “We go onto people’s property and do conceptual design of driveways and patios—I like the design elements, being able to make things pretty, the fastidiousness of taking care of all the details—like deadheading, pinching back, making sure everything’s watered, fertilized.

“You think my house is beautiful,” she continues, “you should see my garden! Do you want to come outside with me?” We go outside, though I’m 3,000 miles away. She revels: “Gardens! I love gardens!” Her six-year-old foster child, Dominic, follows her (us!) out, and she sends him back to put shoes on. He’s been with them for seven months, and they’re hoping he’ll stay. “Dominic is amazing and has a potential for greatness if only he’d embrace it,” she says, in a stage voice intended for him to overhear.

Chandler has no room in her life for acting, though she misses it and would go back “in a heartbeat” if the circumstances were right. But they aren’t, and she refuses to dwell on it. “I believe happiness is a choice,” Chandler tells me, a garden Buddha in view behind her. “And I choose happiness. I don’t choose regret.”

At one point in her house tour, Chandler sits in front of a wall hanging I recognize: It’s a piece of a mural, torn from an action painting made by classmate Jessalyn Gilsig over the course of a performance of The Trojan Women: A Love Story, adapted by Charles Mee and directed, in their final semester at ART, by Robert Woodruff, who would later succeed founding artistic director Robert Brustein as the head of the theatre. I remember these arresting wall murals and other drawings by Jessalyn, who’d played Andromache, “attacking an expanse of brown paper in hysterical response to the trauma of Trojan ruin” (as I wrote then). Chandler tore one off the wall 20 years ago and, when she moved to Connecticut, “spent a fortune getting it framed.”

Canadian-born Jessalyn has continued to draw—you can see her work online and also in the film The Station Agent, in which she created the original art “painted” by Patricia Clarkson’s character. She’s continued acting, too, establishing a career as consistent—maybe cumulative is the right word—as any of her peers. She went back to ART for a season in the company and then on to New York, where she was based for five years, while building a regional theatre and Off-Broadway career, including a “great experience” in “the first contemporary comedy I’d ever done,” the premiere of David Ives’s All in the Timing. She supported herself through theatre, commercials, and voiceovers, while periodically doing an ungodly amount of paperwork to renew her work visas. Her first on-screen job, landed while in New York, was in The Horse Whisperer with Robert Redford. That same year she went to Seattle’s A Contemporary Theatre to perform in Scent of the Roses with Julie Harris. From there she flew to check out L.A.

In the way they so often do in the arts, disappointment and opportunity, calamity and good fortune, arrived together, tangled up. Jessalyn had met television producer David E. Kelley when she’d been a guest on “The Practice,” and soon after he offered her a lead on a new series. But she was headed to Broadway with Julie Harris and Scent, so Jessalyn declined. In rehearsal in New York one “horrible day,” the cast learned that their financing had fallen through. What Jessalyn remembers best was the diminutive Julie Harris, all five feet of her, standing up before the producers and, with fury and conviction, declaring, “You can’t do this to actors! You can’t make promises and break them. Everyone has made sacrifices to be here.”

Then came opportunity. Within the week, Jessalyn’s phone rang, and it was Kelley again. “I heard your money fell through,” he said. “Would you come out here?” Her two-year run on “Boston Public” began a TV career of leading roles on such groundbreaking shows as “Nip/Tuck” (four years) and “Glee” (two years, plus return engagements) with creator Ryan Murphy, and, till early this year, three seasons on “Vikings.” It also began her adjustment to life in Los Angeles.

Though she returned to New York in 2003 for a production of Fifth of July at Signature Theatre Company (on the night I saw the show, there were several of her classmates from ART in the audience—a moving mini-reunion), the Lanford Wilson play would be her last onstage performance, and, at least until now, her only professional return to New York. Jessalyn had re-met and started re-dating her high school sweetheart in Los Angeles. They got married, bought a house, and “before you know it, you have roots.” Unlike Chandler’s roots, however, Jessalyn’s didn’t preclude acting—she has ridden the crest of TV’s post-millennium boom, and she’s happiest when she’s working. Her marriage has since ended, and now her choices are driven by her strongest connection: love for her nine-year-old daughter, Penelope.

“Having my daughter is the best thing I ever did in my life,” she avows. “It makes me think faster and make choices faster. I think I’m better at my job as a result.” Jessalyn has a “little plan in the back of my head,” she elaborates. “When she’s grown and off in her life and I’ve managed to set her up to do whatever she dreams of doing—then I’ll go back to theatre.” Right now, though, TV pays the bills. “I need to earn for her. I’m the sole breadwinner. I’m totally financially responsible for her, 100 percent. I still get to do really interesting work, but it’s all for her.”

The hardest challenge now is when the work takes her away. “I do leave her sometimes, and it’s been very hard.” During the six months a year that “Vikings” was filming in Ireland, however, Penelope was there with her, studying at the local lycée. And as she gets older, Jessalyn is more aware of the cycles of work and she stresses less. In the “feast or famine” of Hollywood, she’s finally seeing the flow. She knows she’s getting better and better at her craft.

“When I got out of school, none of us wanted to do TV, but it’s been so good to me—interesting and varied.” Early on she struggled with being an “unglamorous person” in glamorous roles, but “as I get older, I think so much less about how things are perceived and much more about what I’m doing in that moment. To be able to have a vocation where you’re trying to bring truth to a moment, elevate writing, bring some energy, and hopefully entertain—that transcends mediums.” Then there’s the plan in her head. “If the theatre will have me, that’s where I’ll go, of course.” She tells me that late in life Julie Harris had a stroke that impeded her speech. “So she studied mime! Never quit!”

Twenty years ago, as her classmates were posing for group photos for the cover of this magazine, Jessalyn was back in Montreal, awaiting yet another work visa. Finally, two years ago, she became an American citizen. She went to City Hall, one of maybe a thousand. It was very moving, Jessalyn says. People were crying. Penelope was with her.

Todd London is executive director of the School of Drama at the University of Washington. The lives of eight more actors will be explored in next month’s edition of American Theatre.