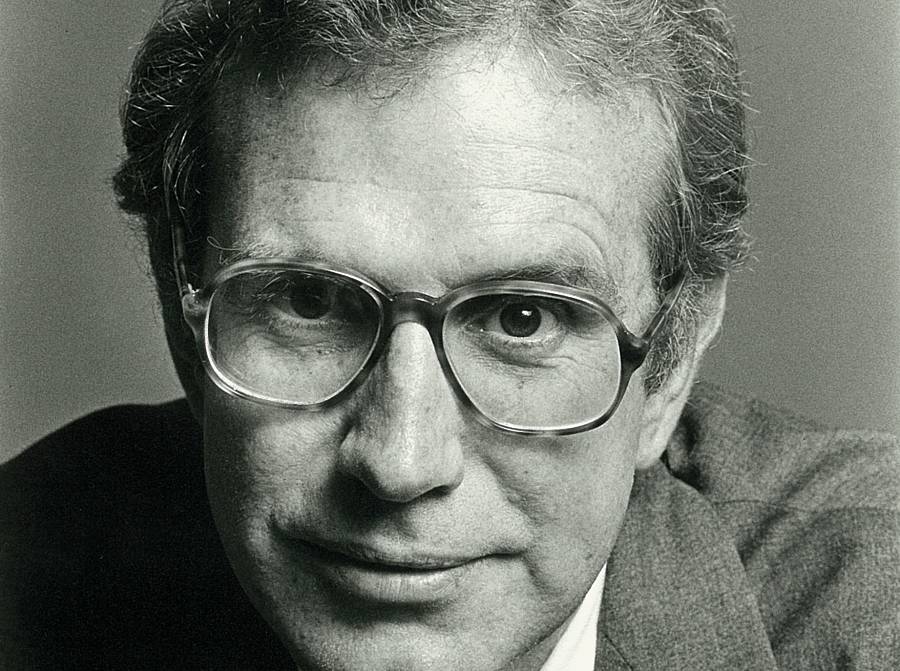

It would be easy to write about the triumphs of Peter Culman’s spectacular career, spanning 40 years, 34 of them at the helm of Baltimore’s Center Stage. There he built its remarkable home at the old Loyola College and Preparatory School on Calvert Street; presided over 22 years of operating in the black while insisting on placing artist compensation at the top of his priorities; helmed the League of Resident Theatres for two terms, leading multiple national labor negotiations whilst never losing sight of his commitment to continuously improving the working conditions of artists; mentored scores of young managers, particularly championing women, who would go on to run their own organizations. But those outcomes would not capture the essence of this man. For those of us who had the privilege of working with Peter, we learned as much from his deeds as from his words.

I first met Peter in 1978 in the offices of Theatre Communications Group, where I was interviewing for a fellowship in performing arts management. He was one of six senior managers who would select the fellows. I was a bundle of nerves facing those 6 doubting faces. When asked where I imagined myself in 10 years, I made what I thought was a witty reply, only to be greeted by stony silence. Peter jumped to my rescue, saying, “Oh, come on, where do any of us think we will be 10 years from now?” The ice was broken and I was smitten.

Six months later, and continuing for the next 10 years, I worked for Peter at Center Stage, soaking up his wisdom and admiring his grace. For Peter everything started with a cup of tea. It was the ritual of making tea that drew us in—a quiet, thoughtful process of selecting the right leaves and steeping it just long enough. Peter was always more interested in the process than in the outcome. Hence the scores of half-filled cups with the dregs of cold tea and scary-looking leaves scattered on his desk and credenza. When I wanted to get on to the next new thing, he would say, “There is a fire in your belly, but remember, you don’t know it by doing it once, or doing it twice; you have to do it many times before you know that it is right.”

He reveled in the experiences of others and was ever so curious and moved by our stories. It seemed as if the more you revealed to Peter, the more he wanted to know. He listened closely, probed deeply, and cried often. One of Peter’s favorite quotes is from the Quaker author and philosopher Douglas Van Steere: “To listen another’s soul into a condition of disclosure and discovery may be almost the greatest service that any human being performs for another.”

Jesuit-trained, Peter was a deeply spiritual man, guided by his faith and fascinated by the faith of others. He and his wife, Anne LaFarge “Sita” Culman, regularly convened an interfaith group in search of spiritual intersections. He taught homiletics (preaching) for decades at St. Mary’s Seminary and University and served as a trustee of the Baltimore-based Institute for Christian & Jewish Studies. The institute later established the Culman Series in honor of Peter, as a way to bring together Jews and Christians for the purpose of shared stories.

It should come as no surprise that Peter was an accomplished fundraiser. I accompanied Peter on hundreds of donor visits and was always amazed that he could talk for hours with patrons about everything other than their gift. It was not unusual to be deployed to change the light bulbs at an elderly patron’s home while Peter was brewing tea. Once, during a visit with a renowned Baltimore dowager, she fell asleep in the middle of a quiet moment. Peter winked at me and promptly fell asleep as well. My job, I surmised after getting over my shock, was to wait a respectful length of time and gently wake them up. On the way back to Center Stage, I asked Peter if I should have handled it differently. He laughed and admitted that he brought me because the last two times he visited the same thing had happened and he needed a wake-up helper. When I suggested that a warning would have been nice, he replied, “That wouldn’t have been as much fun!”

Years after I had left Center Stage, Joan Channick told me that she was interviewing with Peter for the associate managing director position. I warned her that he would probably cry during the interview and not to be thrown by that. Later, when I asked her how it had gone, she said, “He cried twice,” to which I replied, “You’ve got the job!”

The last time I saw Peter was three years ago, when he sailed, unannounced, into my office at Yale School of Drama with Sita and his eldest son, Sean. They were in New Haven for an exhibition of John LaFarge paintings at the Yale University Art Gallery. Accompanying Peter to the gallery, I found him as impish as ever, giggling, napping on the museum benches, joking about his then-quirky memory, and yes, asking many questions and weeping at the drop of a hat.

Several months ago Peter’s other son, Liam, shared a poem written by his 10-year-old daughter, Peter’s granddaughter, Ellie Culman. Friends observed that this poem sounded like Peter. Indeed, for me it brings to mind the curiosity and spiritual splendor of my mentor and dear friend Peter Culman.

Lift Off

by Ellie Culman

Looking up

I close my eyes, and open my mind

Anything can happen when you imagine

Your mind takes you to a magical place

Where anything will take you higher

When you imagine

Your heart takes you higher

Higher is where anything can happen

But before you go

You must believe the lift off

3…2…1

The moment of clarity

Is the moment of the lift off

3…2…1

Lift off

Victoria Nolan is deputy dean of the Yale School of Drama, managing director of Yale Repertory Theatre, and adjunct professor of theatre management.