In Rajiv Joseph’s new play, which premiered at New York City’s Atlantic Theater Company in June, two humble guards get to witness the unveiling of the Taj Mahal in 17th century Mughal India—and are then given the worst “cleanup” job imaginable. Two followup productions have already been announced: at Los Angeles’s Geffen Playhouse, Oct. 6–Nov. 15, and at Washington, D.C.’s Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company, Feb. 1–28, 2016.

For an interview to accompany the complete text of Guards at the Taj, published in the September issue of AT (and available only in print), Joseph sat down with John Clinton Eisner, artistic director of the New York City’s Lark Play Development Center, where Guards, as well as other plays by Joseph (including his Pulitzer finalist Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo), have been developed.

JOHN CLINTON EISNER: What made you think to write this play, and how did the idea develop over time?

Rajiv Joseph: My dad is from India, as you know, and I think I’ve been to the Taj Mahal now three times—when I was 10, when I was 22, and when I was 40. The first time I went it made a big impact on me, especially the stories my aunt was telling me about it—legends and myths of what went into the Taj Mahal, why it was built, how it was built. So when I got out of graduate school, I was writing this large-scale play about the Taj Mahal that involved Shah Jahan, the emperor, and the architect, Ustad Isa, and many other characters. It was an unwieldy mess of a play. I eventually abandoned it and came to realize that there was one thing that was interesting about it: the two smallest characters, the two guards. It was a long time before I put pen to paper again with it. I wrote the first scene of it—I want to say it was in 2012—and I was very happy with it. I immediately thought that I wanted my friend Arian to play the part of Babur. I met with him and he suggested Omar Metwally. So the two of them came with me to the Lark, first to their Playwrights’ Workshop program that Arthur Kopit leads—I guess it was almost three years ago. Since then, there’s been this sort of engine behind this play and this relationship I had with these two actors.

It’s really interesting what you’re saying about the size of the version you wrote initially, in response to the epic question of where you come from and who you are, versus what it became. Can you talk a little bit more about this Rosencrantz and Guildenstern thing? What is it about choosing the two smallest, most insignificant people that actually mean something to you?

That’s a really interesting question, and I don’t know if I’ve ever actually explored why. As I was writing that first draft, I was getting into this philosophical question of power versus art. That’s a provocative and interesting question, but it was yielding a very didactic play: The people in power are bad and the artists are good. That’s boring. Who wants to see that? We all know that already. [Laughs] It’s not at all interesting.

Unless you’re in power.

Unless you’re in power, yeah. But I couldn’t let go of this idea of these legends about the Taj, and the decree I had always heard in relation to Shah Jahan—that after it was completed, he was so moved by the beauty of the Taj that he decreed that nothing so beautiful shall ever be built again. Unpacking that, I was like: If that is true, then these characters have to perform this act, which is chopping off all the hands of the artisans who built it. If a guy is contemplating that in the way that Babur does, what does that start to mean to him? The conclusion that comes through the funnels of Scene 2 is that he killed beauty—that if nothing more beautiful than this will be built again, then beauty itself will die, is dying as we speak, because we’ve already done this act. That has this earth-shattering effect on Babur as an individual, in that he now blames himself for the death of beauty. That to me is very interesting—much more interesting than power bad, artist good.

It’s also a love story in the context of a world that doesn’t permit love or beauty. The struggle of these two men, who I think both want to do the best thing for each other, becomes incredibly human and personal. And I don’t detect any loss of historic scope in paring it down to the real human elements.

I have to credit so much of that to the actors. They were so invested in the story and these characters and the life of the play—they really felt that they were a part of something so important, and that made the writing important to me, you know? Not that I wouldn’t think so, but it enhanced the experience for me.

Their thoughts were often impassioned and fervent. We did a reading of it a year and half or so ago, and we went out for beers afterwards. I went to the bathroom, and when I came back, they were giving me this look, you know? They were like, “Listen, not to step on toes, but…” Their point was that I was still jumping ahead in time; after the second scene with all the blood, we went ahead 10 years, and then 10 years after that, and all this other shit was happening to their characters. And the actors were like, “You have this second scene, which is so incredible and theatrically is going to be so intense if it’s done right, and then you forget the consequence of that—you jump on to some other new story. Why can’t we live in the consequences of what they’ve done? That seems to be the hinge of the play.” They, of course, were right.

I think that was a hugely successful change.

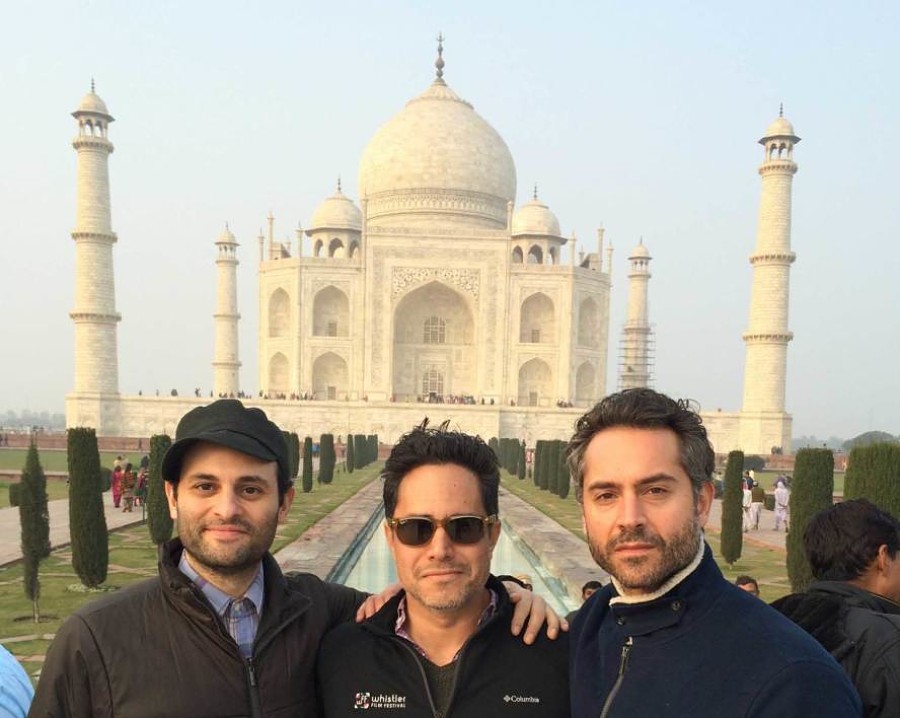

Yeah! And you talked about how it’s very much a love story—a story of brothers, friends—and Omar and Arian, who’ve known each other and worked together for 15 years, rubbed off on this. And then, of course, our opportunity to go to India together in January and see the Taj Mahal and wander through Delhi and Jaipur and Agra and absorb the culture and the architecture of the Mughal empire—it was a bonding experience that made this entire journey and production at the Atlantic all the more significant.

When you started to work with Amy [Morton], what new perspectives were brought to it?

I had always known she’s a genius actor. As I got to know her more as a director, I was even more blown away by her vision and her steady hand at the helm of this ship. Those guys had known her; the three of them had all been in Homebody/Kabul at Steppenwolf about 12 years ago, and that’s where they all met. One of the things I really appreciated about how she saw it is she just didn’t want to pull any punches. I was willing to pull some. But she wanted there to be as much blood as possible.

How many gallons of blood were there?

I don’t know how many gallons, but there was, you know…

My 16-year old was estimating. He said, “It’s gotta be between 20 and 30 gallons.” [Laughter] I mean, it’s a room of blood. Every time that the lights came up on that scene, I just couldn’t believe that we had somehow managed to do that.

Even in that scene, there’s a lot of humor, and we laugh because we really can’t begin to take on how enormous the trauma is. Then later on, the act of watching one friend cut another friend’s hands off is one of the most horrific and upsetting experiences I’ve ever had in the theatre. How did you talk about that?

That ended up being the most difficult scene for both actors. They are good friends in real life and they are playing best friends, and here they have to do this thing—it was deeply affecting them. They stopped rehearsal once, and Arian was like, “This hurts my feelings, this scene. I don’t know how I’m going to do this every night.” And Amy, who was sitting in an office chair, wheeled over to him, and I thought, “Oh, she’s gonna comfort Arian now, like a mom.” She said, “Listen pal, you gotta develop some calluses. This is not a healthy business, my friend.” And that was it. [Laughter] And the guys were like, “Okay, who knows better than Amy Morton, who has done August: Osage County and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? on Broadway every night for however many months and years?” Amy knows the right thing to say at the right time, and she carries with her such integrity that when she says something like that, it really hits us all real deep. I also felt it was an acknowledgement of the difficulty of the material in the play, how it’s just not healthy.

There’s a line in this play that I love, and it just breaks my heart every time, and that’s when Babur says to Humayun just before he cuts his hands off: “This is gonna fuck you up.” Can you tell me about how other audiences have reacted?

Absolutely. When you’re so close to a piece, you don’t necessarily know how an audience is going to react to it. And I don’t think I had a concept—even after the intense rehearsals with the guys, for me, I always thought of it as a comedy. But the last 20 minutes or so of the play are particularly grueling, and you can’t expect anybody who has been engaged with it fully and has appreciated the play, to be able to come up and slap you on the back and be like, “Hey, great job,” afterwards. I felt that most people were like, “Okay, I need a drink before I can process this and talk to you.” At first, I was going up to my friends or my parents and being like, “Hey, so what did you think of the play?” And they would just nod and walk away. And I’m like, “What the hell is wrong with everybody? Did everyone hate this play?” And then I realized, “No, they need a drink. And so we’d go get that drink.”

Have you learned anything about your writing process or what you want to focus on next through making this play?

The thing that I enjoyed about writing this play was balancing between two times—something that takes place 400 years ago, but using a contemporary vernacular and finding a magical realism between those two in some ways. It was very freeing to me. I’m finding that historical stories are easier to write.

That’s so interesting. Can you talk a little bit more about that use of contemporary vernacular?

I’ve gotten the question a lot—not only about the contemporary vernacular but also the lack of an accent. When people were auditioning in L.A. and thought we were using accents, we kept on saying, “No accents, no accents.” I had finally put a note in script: No dialect should be used here. There’s a hard logic to it, which is that if this were realistic, they wouldn’t be speaking English at all. If they put an accent on, it’s even faker. And really, it’s about about two guys who are friends who are talking to each other and trying to figure some things out. Every pair of best friends from a million years ago to now talk in a casual way with one another; they have a shorthand, they have a slang. That was important to me.

This is not going to keep you from wanting to write plays for 20 characters, though?

Not at all! It’s fun to write big-cast plays, but this is my third two-hander that I’ve written, and there’s something about the two-hander that I come back to that I really like. The two-hander always feels heightened to me.