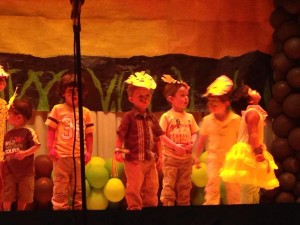

Last week my nearly three-year-old son made his stage debut in a probably unauthorized version of The Lion King at his summer day camp in Queens. Bewhiskered with face paint, he peered out from under a paper-plate lion’s mane to find our faces in the audience, and while he was at it, remembered some of the playful, dance-ish movements he’d been taught (at least as well as most of his sweetly bewildered classmates). Chaos mostly reigned but, needless to say, he was adorable, as was his older brother, made up as a cheetah and enthusiastically stomping through another number on an auditorium stage full of tiny hams. It’s (thankfully) too soon to tell whether they’ve caught the theatre bug, but I can report the unsurprising news that it’s as gratifying to see them enjoying their time onstage as it is to witness their joy in anything.

It was my second theatregoing outing of the week. The first was to see John, Annie Baker’s newest deep-dish helping of epic minimalism, at New York’s Signature Theatre. The acting was considerably tighter there than in my sons’ camp offering, but that’s not the gulf that intrigued me. Instead, the intense hyper-realism of Baker’s haunting and finely wrought play, under Sam Gold’s unblinking if not quite transparent direction, made me think (again) about the question of theatrical artifice—about the common misapprehension that naturalism is essentially a non-style, a default mode, a baseline, a refuge from, or failure of, the imagination.

Among other things, Baker and Gold’s meticulous work—in which the passing of real time onstage becomes almost a character unto itself, as well as a heartbreaking index of opportunities lost, and a harbinger of insignificance and finally death—is a powerful reminder, like the films of Mike Leigh, say, or the object exercises of Uta Hagen, that to recreate “real life” in a narrative form behind an invisible fourth wall is a hugely intentional, determined, and subjective endeavor. It is not arrived at lightly or easily, and in fact goes against the grain of “natural” impulses. Indeed, what my sons’ show demonstrated to me, again, is an insight I’ve ventured before: that to play-act, to be larger-than-life or fanciful, to break the fourth wall and acknowledge the audience—these are the default performative instincts of humans on a stage in front other humans (alongside fight-or-flight fright, of course). They are methodically unlearned, of course, by anyone who wishes to make theatre for a living, and later employed judiciously, if at all. I think that explains why, when professional theatremakers go in a more presentational direction—whether that means Brechtian framing or commedia or direct address or audience participation—it feels as much like a return to form as a departure. These ostensibly form-breaking gambits are in fact a reminder that the universal stage language, which we understand unconsciously as children, is artifice: a dance, a song, a speech.

Film and television may have slightly muddied our thinking about these matters. In much the same way that photography is popularly thought to have made realist painting obsolete (the history is far more complicated), it’s often taken for granted that film—with its illusion of immersion and omniscience, its ability for mic and camera to get up close—now has a monopoly on realism, and that the stage “should” do what only the stage can do and stop trying to recreate or represent. We can watch “realism” on our screens at home, the argument often goes; why go to the theatre to see people chatter on a couch?

You might just as well argue, though, that filmed media’s core competencies are conjuring fantasy worlds that don’t or could never exist (Christopher Nolan, Pixar) or staging quick-cut farces as stylized as cartoons (Tina Fey, Armando Iannucci). Next to these, the theatre is hardly a fantastical place; after all, what is a live theatrical event but a few hours in a room with real people, unmediated by sound, camera, and editing? We have to use our eyes and ears (more or less) unaided and to take it all in in real time, just as the performers must do it all from start to finish. Our senses thus attuned, we may notice more about the characters’ behavior rather than less, and not only what a camera might be able to show us at any given moment. We are both confined to our senses and free to let them wander.

Accordingly, Baker and Gold double down on both the limitations and special opportunities of this shared observational space: John, like their previous collaboration, The Flick, runs north of three hours, and is performed on a single unit set, by Mimi Lien, that’s as intricate as a doily. They neither ask us to pretend we’re anywhere but in a room with a few hundred fellow humans, a few of them enacting a play for the others, nor do they emphasize the artificiality of the arrangement. As in The Flick, this deceptively gentle yet fiercely clear-eyed approach only serves to sharpen our attention, and cleave open our hearts, to the characters’ pain.

I don’t know about you, but I find that kind of theatrical communion as precious and as gratifying as any pulse-pounding musical number—not least because it may indeed be something that only the theatre, for all its inherent unreality, can do.