He is stoic.

It’s hard to say “was”—some people stay in the ether, their essence alive in the very air we breathe.

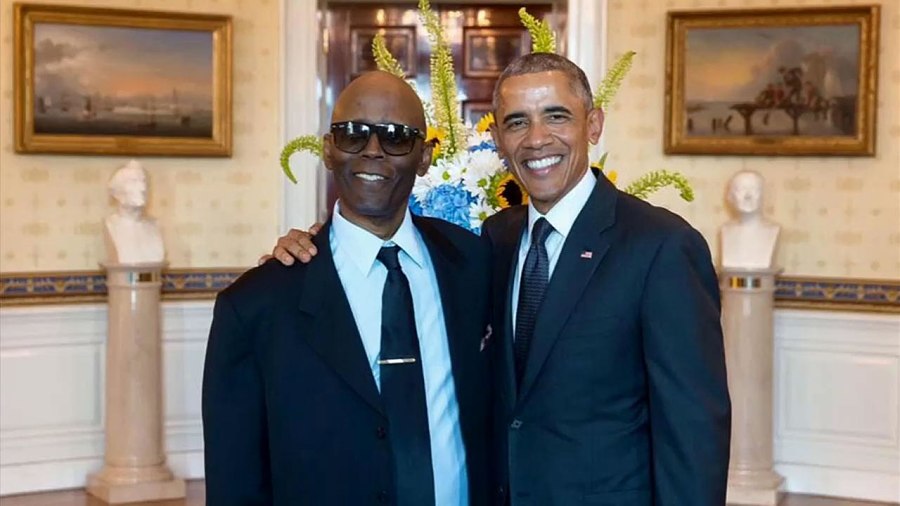

You never how it’s going to go. Just a week or so ago, Lynn Manning was taking a picture with President Obama at the White House. He was writing a piece for the Watts Village Theatre, his artistic home, and he was set to perform on the day he was called back. He left a very full calendar.

Lynn was, by all accounts, many things, but mostly a poet, playwright, and a blind Judo champion.

To know him was to see a life force in action, but it was a metered one. This homeboy knew how to hold on to energy and release it in a balanced life that demanded a lot early and left him in solitude later.

Lynn was even-keeled and full of humor. I met him on the poetry scene first, then later as we started as professional playwrights together, as part of the inaugural group of the Mark Taper Forum’s Mentor Playwright Program. We both stayed for 12 years in that group. It was where we learned the community of theatre and studied with Maria Irene Fornes, Paula Vogel, Mac Wellman, and a host of other amazing mentors.

I got to know him even more closely through the Other Voices project at the Taper, the disability arts program that I was invited to work with through my other dear heart, John Belluso, now long gone as well.

I used to drive Lynn home. We talked writing a lot, but also about his life. I grew up in a very poor barrio not that far away from Lynn in downtown Los Angeles; we had the mean streets in common.

I had fallen in love with Lynn’s work over an amazing adaptation of Buchner’s Woyzeck that he wrote called Private Battle, which was so damn good.

He took great care with his work, and when he read in the workshop, it was always a performance. His being blind hardly ever came into play. He seemed to get very focused, and his fingers did most of the technical work which allowed him to be the actor. He was very assured and laidback; he disarmed you with his disability.

In the car he told me about how he had been blinded in a bar fight, one of the many elements of his disability that he seemed to surprise you with. At one point, he described becoming blind as a gift—an opportunity to experience life in a deep and profound way.

He struggled as a child to hold onto his siblings in the foster care system. Each event in his life was a story of the desire to live. Adversity seemed to energize Lynn into action. Into making art.

He also surprised with his humor, his well-groomed body, his cool stride.

He always seemed to be in a relationship with a woman, and I remember once having this intense conversation about body, pride, sex, sexuality, and manhood, and how he felt he needed to not lose that part of himself in his expression as a disabled person in the world.

I had the honor of producing Lynn’s one-man show Weights as part of the Taper Too series in Hollywood. I had not noticed how buff Lynn was until he did his Judo. I remember the design of the floor, with little raised markers, like Braille, that let Lynn know where he was onstage at any given time. The way he marked his steps and used the audience and lights as focal points made beautiful choreography.

Being blind hardly affected his ability to see the world.

One day in our writer’s workshop, Lynn wrote the most interesting piece, a very sexual, crass, dirty-language comedy. I think he wrote it mostly for shock value, and it worked, because the workshop was in an uproar over it. Maria Irene Fornes was leading the workshop at the time and she asked Lynn to read it out loud. Irene wanted you to open your voice and be heard, to not be afraid of your text, to let it sit in the air, and Lynn gave it a full, lusty reading; he had a very deep sensual voice.

Everyone was in nervous stitches, mostly at how sexual the piece was. Irene looked at him stone-faced. I also remember there was a section of his play where characters insulted each other, and those passages were ridiculously over the top.

After he was done, Irene paused like she always did—she would sort of take a moment to ponder—and said, in true Irene fashion, in her Cuban little-old-lady voice: “Very good, very good…You can’t see me, but I am smiling.”

Lynn was beaming. He loved to make us laugh, to think, to open a world. Disability came late to him and he relayed its effects as if they were new, and of course, for us, they were.

On our ride home in the car, I said to Lynn how I found the piece so profane and sexual—that honestly, I was blushing at the thought that we were sitting in a sterile Taper rehearsal room, and something very special, real, had entered the space which challenged us.

Lynn replied, in his usual wicked way, “Well, Luis, you have to write what you know.”

And he did. Beautifully.

Rest in peace, Mr. Lynn Manning.