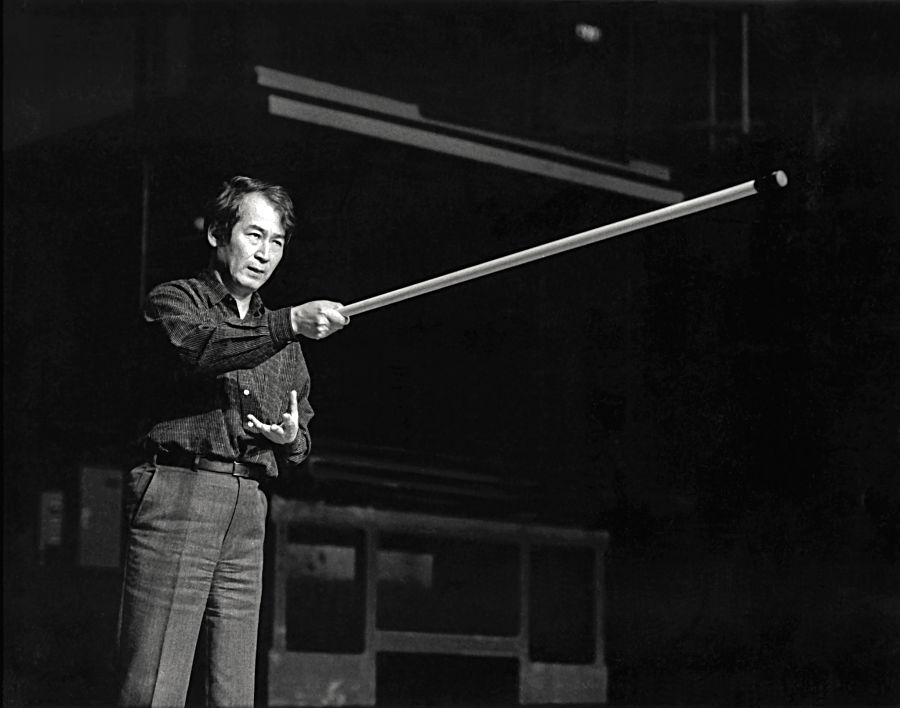

Toga, 1984.

Next year will mark a decade since I first began to make theatre in the village of Toga in 1976.

What led me to Toga was not a pressing desire to leave Tokyo. Indeed, at the time, I had every intention of continuing to work there, and the notion of permanently withdrawing from Tokyo never crossed my mind. Still, when other theatre professionals and journalists in Tokyo first learned of my plans to take the company to Toga, they teased me quite a bit. Was I planning to start a religious cult, they asked, or perhaps going on a Transcendentalist pilgrimage into the primordial wilderness to commune with nature? Even the local papers were dubious about how long I would last in Toga: Wasn’t this, perhaps, just a momentary fling? And wouldn’t all our imported urban culture throw this little mountain village into disarray? In fact, when some of the villagers first spotted certain members of our company arriving in beards and jeans, they wondered if we might be a Japanese Red Army unit which had rented some of their old houses for basic training.

Of course, it was only natural they should react this way. Since none of the villagers lived in the immediate area around our facilities, we trained and rehearsed late into the night, knowing we would disturb no one except the foxes and raccoons. Whatever suspicions we may have aroused, either in Tokyo or Toga, our decision to relocate was not intended as a secret escape into egocentric, esoteric pursuits, but rather as a defiant public statement criticizing the social and cultural centralization of the country around the capital. One might think that, with the goal of protesting this trend, any place outside of Tokyo would have served our purposes. In fact, the reason we ended up in Toga was more or less the same reason that, years earlier, we established the Waseda Shōgekijō on the second floor of a Tokyo café. It was not because the café space fit our ideal image of a 100-seat black box theatre, but rather because it gave us the opportunity to take one more step, however small, toward our artistic ideals.

Being all too human, we often believe it possible to exercise our free will and choose as we please. The reality is that most of the time we cannot. We are forced, instead, to make decisions based on a set of specific, limited circumstances. For me those circumstances were determined by the 1960s Tokyo environment, where I formed part of a generation dissatisfied with the direction in which the country was going as it experienced unprecedented economic growth on a global scale. A side effect of this boom was a “bigger is better” mentality in just about every field, with national policy regionally disseminated by the authorities in Tokyo, much the way parents impose restrictions on their children. As such, the central government gave little credence to the opinions and ideas of local or prefectural authorities, who often understood their particular problems on a much more detailed and practical level. This Tokyo-knows-best mindset had its effect on cultural policy, as well. In the theatre, this resulted in the construction of unwieldy large-scale theatre complexes across the country, with no real plan as to how these facilities would be sustained and no artistic vision driving them.

Searching for a way to realize my artistic vision, I rejected those trends, determined to find a way to produce my work without sacrificing my ideals, and thus founded the Waseda Shōgekijō company. I was able to create a place where artists who shared this same critical, even defiant, point of view on society could work independently of the dominant theatre company structures of the time, without compromising their principles. By fostering an environment focused on artistic and philosophical goals, we were able to overcome obstacles and diversity, achieving more than we ever predicted.

As the rest of society—in fact the rest of the world—was following the credo of “bigger is better,” we sought to return the theatre to its origins. We did not believe that high budgets, immense venues and large audience turnout naturally led to artistic success. On the contrary, it was apparent to us that increasing the financial, physical and social scale of a production often severely diluted its artistic quality and impact. I found that to understand the world, both a central and a marginal point of view were necessary. The Waseda Shōgekijō space, in contrast to the centralized commercial theatres, provided me this marginal perspective, which I used as a springboard to investigate the issues of our time with a small group of uncompromising artists.

Focused on the specific objective of restoring a dense, rich intensity to the theatrical act, we wanted nothing less than to cause a revolution in the hearts and minds of our audience.

In this sense, the move to Toga from the Waseda Shōgekijō space was only logical. In order to intensify our marginal perspective, we had to make it as dynamic as possible, and see where that would lead us artistically. By coming to Toga, a place that could not be more decentralized from Tokyo, I have been able to create from perhaps the most extremely marginal point of view available, deeply influenced by the daily challenges of living in such a place.

Throughout history, theatre professionals have persistently been confronted by various shifting conditions. We may have ample money one time but too little the next; our performance spaces may range from vast to tiny; our audiences may be large or small; reviewers may praise or condemn us. Yet, whatever our production circumstances may be, as long as we have the basic resources necessary to stage our work, we can advance toward our artistic goals. If, along this journey, we remain committed to our choices, sooner or later they will yield tangible results. Will we keep what we discover? Will it have value?

Whatever the answer, I am convinced that any progress we achieve depends on our ability to be continuously inspired and enriched by each new experience. I continue to focus on what I learn in Toga because I recognize its vital role in my worldview. However, this was not so clear to me when I first began.

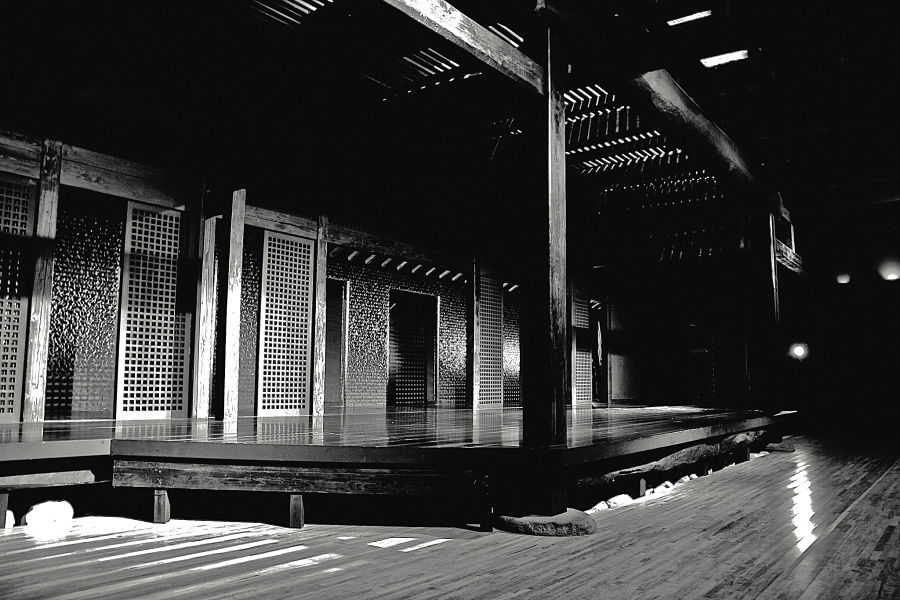

What caused my perception of Toga to change? Apart from the marginalized social perspective I gleaned from being there, Toga’s dynamic natural environment also impacted me profoundly. Just as I was intrigued by the revelations we made about acting in the intimate Waseda Shōgekijō space, Toga’s thatched-roof houses engaged me through their inherent symbiosis with the expansive, ever-changing mountain climate, relentlessly challenging me with a new sense of space. The vital, protean quality of Toga inspires me still, and I will doubtless continue to make work there until I die. This staunch conviction stems from the fact that, in today’s Japan, it would be nearly impossible to devise a performance environment more closely suited to my philosophical and artistic sensibilities.

My company does occasionally perform in commercial spaces like Tokyo’s Imperial Theatre and Iwanami Hall, despite the fact that they don’t reflect my ideology. Obviously, I am grateful when these theatres ask me to make as few compromises as possible. Nevertheless, when working in such venues, I invariably open myself up to censure. At Iwanami Hall, for example, the critics chide me for enslaving my originally wild iconoclastic nature to academicism. At the Imperial Theatre, on the other hand, they reprimand me for having sold out to commercialism. The fact is, no matter what the field, the industrial mentality in Japan persistently lashes out at anything attempting to go beyond that which has gone before, or interrupt the status quo—as if such groundbreaking work were completely irrelevant. Likewise, the attitude of my critics toward innovation reveals their misguided priorities. They forget that even when theatre becomes “enslaved” to academicism or “sells out” to commercialism, the artistic quality and integrity of the work must be valued above everything else. If theatre that reaches new pinnacles artistically also garners the attention of academic or commercial interests, more power to it!

In any case, no matter which standard we use to measure commercial success in the theatre, our activities in Toga inevitably fall into the red. My company, comprised of roughly 40 members, is bound together by a kind of volunteer spirit that would normally characterize a religious group. We work in a village whose inhabitants are struggling to make a living and have no leisure time for the theatre. No matter how many months we might perform, we could never sustain ourselves economically on local audience support alone. The village itself is far from self-sustaining. Even though Toga’s annual budget is more than seven million U.S. dollars, the national government subsidizes 95 percent of this. Like my theatre company, the village must attract money from authorities in Tokyo to survive.

The salient point here is that in a highly capitalistic society like Japan, every individual and organization must operate within the commercial system. There are people who imagine it might be possible to survive without doing so, but such conjecture makes little practical sense. It would be akin to believing I could maintain my operations in Toga with nothing more than an enthusiasm for its unique performance spaces.

Another issue which must be considered in analyzing our presence in the village is the fact that Toga is a textbook example of Japan’s post–World War II urban exodus—a phenomenon whereby many rural villages have experienced a drastic and consistent drop in population. While I don’t pretend to be a government official or political scientist, I can see clearly that people are leaving Toga—so quickly, in fact, that I wouldn’t be surprised if Toga soon has problems justifying itself as an independent municipality. Villages all around Japan seem to be thinning out in this manner. Since no tactics have succeeded in quelling the exodus, the few enduring residents in Toga now find themselves inhabiting a sizable expanse of land. It would seem that this depopulation of the countryside was particularly striking in our recent period of high economic growth. As a result of the postwar energy revolution, Japanese society has become fully industrialized, and the ensuing prosperity has triggered a migration to urban areas. In the process, Japan has grown greatly dependent on oil, electricity and gasoline, causing the villagers who once provided firewood, coal and charcoal to lose their livelihoods.

Conversely, as the city populations have swelled, secondary and tertiary industries have expanded, so that villagers no longer employed by the primary industries of farming and forestry have converged on the cities to seek work. The development of mass transit networks and global communications systems have also contributed to the urbanization of the villagers’ mentality, encouraging an even greater withdrawal. Now that the era of rapid economic growth has more or less come to a close, the benefits of urbanization are being reevaluated. Still, the depopulation of the countryside persists, and villages such as Toga continue to shrink.

For the mayor of a village like Toga, the highest priority is developing a plan that keeps the number of people leaving to a minimum. Starting with the Toyama Prefectural Office, followed by the Ministries of Construction, Agriculture and Forestry, he goes from one government agency to another, petitioning for subsidies. As mayor he knows that even if all his petitions are successful, they still won’t be enough to solve the larger problem he faces. Yet he cannot sit idly by and lament the situation. As long as one person still wants to live in the village, it is his duty to improve the conditions there as much as possible. From an outsider’s point of view, the mayor’s efforts resemble those of Camus’s Sisyphus, or of a bicycle rider who’s stopped moving forward but still must keep his bike from falling over.

As I started working in Toga, I began to experience the contradictions inherent in the structure of modern Japanese society and so came to share this sense of isolation that the local politicians feel. For this reason, I did everything I could to cooperate with the mayor and his policies to help reduce the depopulation of the area. Of course, I never intervened directly in any of the village’s political activities, which would have been overstepping my boundaries. Still, I tried to do what I could to help curb the urban migration and perhaps even bring about an influx. In making such efforts, the presence of my theatre company was indispensable. It was quite clear to me that if the population declined any further, we could no longer function in Toga no matter how ideal the environment might be for our work. At some point, the minimum population threshold would be breached, so that even the village’s basic operations would come to a halt. If any of the financial aid or local tax subsidies were to shrink, transportation facilities and snow removal services would be reduced, low-cost housing would no longer be available, and our theatrical activities would be directly impacted.

In the end, my theatre company cannot run itself as an independent entity. If the village of Toga ceases to exist our work there must also end. Such is the interdependent relationship between company and village in a region like ours. In Tokyo, on the other hand, most theatre professionals cannot fathom the idea of the city disappearing, even if it were put forward as an abstract proposition. The word “disappear” itself would be meaningless to them. Such ideas are entirely remote from their daily reality. I believe, however, that not only Tokyo, but all of Japan as we know it may very well disappear one day. There is certainly a strong possibility that Toga might vanish altogether. I am surrounded everywhere by evidence of this, from the practical problems I experience firsthand to the statistics I read in print.

Without the villagers, the mayor would not exist. Similarly, without actors, the director does not exist. The function of a theatre director is not like that of other artists in other forms, where the final product takes on an independent visual or textural form. Rather, the theatre director’s essential job—at least for a founding leader of an ensemble that works in a continuous context like mine—is to stand at the junction of various intersecting artistic endeavors and manage to strike a harmony among all of them. He can never rest on his laurels, but must tirelessly reinvent his company to face new challenges while also maintaining their relationship with the constantly changing outside world. Simply put, the director’s job requires him to discover the best way to develop his company and then obtain the means to do so. He must relentlessly renew his vision, then strive toward it on a trial-and-error basis. To facilitate this, he must also generate a shared way of working with his company that allows each individual to undergo a continual transformation both as artists and individuals. Finally, on the basis of those transformations, which are difficult to stop once set in motion, he must devise a communal hope for the future.

As the director executes his work over time, not only do his goals evolve but he also experiences personal changes, while his creative impulses manifest themselves in new, unpredictable ways. He must constantly make choices regarding casting and, in certain circumstances, the text and performance venue as well. In my case, as a founding director, I am also responsible for the economic welfare of my company. I cannot simply make decisions based on some personal whim. I must observe changes in our audience, even in society itself, and base my agenda on what I ascertain. I cannot simply amuse myself with my work in some narcissistic fashion. I live in the world, and as such tenaciously make connections with everything around me. To what extent should I try to wrestle with these connections? This is the enigma facing the director, and herein lies his most demanding task. Put another way, connections inevitably accumulate between a theatre director and the society in which he abides. The director who is aware of the influences acting upon him can use that knowledge to make artistic choices that will consistently engage his audience. Such continuity validates his work, ensuring him a genuine vocation.

Perhaps, in another sense, the very notion of continuity or consistency in theatre work is outdated. One might even argue that such an idea runs counter to the creative impulse, which spontaneously springs up and then vanishes as quickly as it came, and that from this very impermanence emerges the true theatrical moment that transcends time. I agree that a continuity of the creative impulse can never be anticipated. It is, like human life, essentially ephemeral—here one moment, gone the next. Thus, the theatre director, or any artist for that matter, can never consistently predict how and when inspiration will surface. However, what artists can do, in fact what we must do, is create continuity in the environment that surrounds us. For me, this has meant maintaining a group of people that shares a common worldview and collaborates over long periods of time in the same context. Without this continuity of artistic infrastructure—space, theory, training, company, artistic vision, philosophy and the like—the creative impulse cannot blossom. However spontaneous and inspired such impulses may feel in the moment, there is simply no accumulated history to support them, and hence no way for this spontaneity to become inevitability. In the world of competitive sports, great inspired plays are only able to take place because the athletes have spent years continuously preparing for such extreme moments.

We often think of inspiration as something that happens in the beginning of a creative process. But for me, true inspiration only happens after a long period of training, when such impulses can be processed in a skillful way. Take the case of acting. In an environment based on continuity, improvised or spontaneous impulses cannot help but be connected to all the work that has gone before, in dialogue with the performer’s own instrument, the other artists and the physical space. Under these conditions, the creative impulse inevitably leads the artist closer to his or her ideal state of being, where he or she may experience freedom. At such moments—be it with music, literature or theatre—artists open a window through which they can clearly transmit their singular point of view and stimulate the audience’s imagination. It is for this reason that, until my death, I will continue to focus my efforts on exploring the innumerable artistic possibilities that exist within the continuity of human actions.

If I had to choose one thing I am most thankful for since having come to Toga, it would be the opportunity to encounter certain courageous individuals who understand that, despite whatever desperate conditions they may face, they must continue the quixotic pursuit of their impossible dreams. Armed with this knowledge, these spiritually enlightened artists have achieved a self-awareness that allows them to lead fulfilling lives. To paraphrase Sartre, I have finally been able to see at close range a few individuals who truly understand that life is a futile, passionate play, who are nevertheless driven by the desire to battle on, fighting the lonely fight of the defeated, in the face of hopeless odds.

This excerpt is reprinted from Suzuki’s book Culture Is the Body, which was released by TCG in June.