Maybe it’s something in the water. Or, given that we’re talking about Minneapolis and St. Paul, something in the Mississippi. Change is coming—and in some cases, has already arrived—for the performing arts in the Greater Twin Cities. As Minnesota Playlist’s Derek Lee Miller noted in a column in April, a surprisingly large number of theatres in the area are experiencing leadership changes. Doug Scholz-Carlson took over as artistic director of Great River Shakespeare Festival in 2014. The Paul Bunyan Playhouse’s artistic director, Zach Curtis, is stepping down. Michelle Hensley, the beloved founding artistic director of Ten Thousand Things, has discussed plans to retire in the next few years. Tim Jennings, the managing director of Children’s Theatre Company, is leaving for a job at Ontario’s Shaw Festival.

All of these changes, though, pale in comparison to the tectonic turnovers at a few high-profile theatres. Mu Performing Arts, the region’s flagship Asian-American theatre, got a new artistic director two years ago when Rick Shiomi handed the reins to Randy Reyes. Penumbra Theatre, one of the nation’s oldest and largest theatres to remain from the Black Arts Movement, is transitioning from founder Lou Bellamy to his daughter Sarah. The Jungle Theater’s founder, Bain Boehlke, just handed his theatre to the now-former-head of the UT Austin directing program, Sarah Rasmussen.

Most sea-changing of all, of course, was the news that after more than two decades and a massive building campaign, Joe Dowling, artistic director of the Guthrie Theater, would leave this past summer. The theatre is now in the hands of Joseph Haj, who for eight years had been the producing artistic director of PlayMakers Repertory Company in Chapel Hill, N.C. Haj, the son of Palestinian immigrants, will be the historic theatre’s first a.d. of color.

What Miller dubbed the Big Turnover has national implications: By the end of next season, one of the nation’s most important African-American theatres, one of its most important Asian-American theatres, and one of its most renowned LORT theatres will be in the hands of new leadership. The Jungle has announced its intentions to move into the national new-play conversation. Minneapolis’s theatre scene, which is well supported and very locally focused, appears to be prepping itself for a more national presence.

According to one consultant who works on arts leadership transitions who wished to remain anonymous, “There’s no bigger decision a board of trustees makes than the choice of a new artistic director. The choices the artistic director makes about what goes onstage and what is in the community affects how donors react, board inspiration, staff motivation, and morale—you name it.”

Bringing on a new a.d. isn’t just a big decision; the process of change itself is also suffused with risk. Some artistic director transitions go smoothly, enriching and changing theatres for the better—but some are infamous disasters.

“If there’s not real clarity at the beginning,” the transition consultant told me, “particularly around whether, and how much, change is necessary, that leads to a failed search. Failure can also set in…if there’s not truth-telling among the search committee and the candidates, like when a theatre doesn’t provide their accurate financials to a candidate, or doesn’t reveal they’re losing their space.”

A version of that nightmare scenario happened at Seattle’s Intiman Theatre in 2009 and 2010, in the most notorious recent example of a botched artistic transition. Incoming artistic director Kate Whoriskey, who succeeded Bartlett Sher, discovered only shortly before it was made public that the theatre owed $1 million to creditors and needed an immediate infusion of $500,000 just to keep the lights on. Amid accusations of miscommunication among the board and the managing director at the time, Whoriskey left the job shortly after taking it. After a few dark seasons, the Intiman is now in a slow, steady recovery under producing artistic director Andrew Russell.

No one is anticipating a similar implosion at any of Minneapolis’s theatres. “We’re watching a shift happen with the leadership of the theatre scene here that I think is profound and exciting,” said Marianne Combs, an arts reporter for Minnesota Public Radio. “We’re seeing leadership change in ways that are more diverse. We’re seeing more female leadership, more people of color. I would like to think this will have a real impact on the diversity of stories we see as audiences onstage.”

Alan Berks, playwright and editor-in-chief of Minnesota Playlist, agrees.

“I think all this turnover is fantastic,” said Berks, who is also a member of Workhaus Playwrights Collective. “These are all great people and great hires.” He expects them to build on this pivotal moment in Minnesota’s theatre history. “There’s a lot more immersive, experimental work done at a high level of quality. There’s a lot more work in the mid-sized theatres that is new voices, that is diverse. Theatre in Minnesota right now is as good as I’ve ever seen it.”

If they don’t provide cautionary tales, the leadership transitions at Mu, the Jungle, Penumbra, and the Guthrie do offer observers a range of different models for charting a theatre’s future. Three of these theatres were founder-led until now; two of them promoted in-house candidates to the top spot; two reached outside of the Twin Cities.

Perhaps no transition is as peculiar and as radical as at Penumbra. Not only is founder Lou Bellamy handing it to his daughter Sarah, but the transition itself is taking place over multiple years, with both Bellamys running the theatre together in the interim.

The kind of material presented onstage has changed sharply, as well. Whereas the 2011–’12 season was a fairly traditional slate of offerings including The Amen Corner, Two Trains Running, and I Wish You Love, the 2014–’15 and 2015–’16 season slates have included works by the likes of Lynn Nottage, Dominique Morisseau, and Roger Guenveur Smith.

“We’ve already seen Sarah Bellamy’s impact,” Combs noted. “Her first season was dedicated to women’s voices—that was a huge change. Now her next season is focused on social justice issues raised by Black Lives Matter. It’s a big difference.”

Along these lines, the new Penumbra includes films, panel discussions, one-off presentations of solo work, and discussions of visual art alongside the play programming. For Sarah Bellamy, the new season recognizes Penumbra’s place in the community.

“To my mind, looking at Penumbra, we’ve always been a space for this community to come together and create a conversation that’s not happening anywhere else,” she said. “When I think about curating a season, what I look at is: Where is the community right now? Where can we put together a conversation with care and depth and rigor? How can we forward social progress?”

Practical considerations sit at the heart of the new season, as well. “We’re trying to be sticklers about financial sustainability. How can we do more with less? It’s a big question for us.”

Bellamy credits her long history with the theatre and her father’s faith in her leadership in allowing her to make such rapid change. “I came back to Penumbra about 10 years ago to build up the education and outreach programs, and I found this to be a really fertile place to test ideas and draw together the connection between art and social change.”

Bellamy, who grew up in the theatre playing on the sets and hanging out with the actors before a career in academia, found that, upon her return to Penumbra, her “passion reawakened to the power of theatre to change lives and minds around race and racial justice. I saw the platform that’s here. It made me think: This is a way to do everything you’ve wanted, just maybe not in the way you thought you would do it.”

When Lou Bellamy began thinking about retirement, the two began discussing what a Sarah Bellamy–led Penumbra might look like, and how to stage a graceful transition. “Having time for us to walk together is really important,” Sarah said. “We are the largest African-American theatre company to be founded during the Black Arts Movement; we are among the oldest black theatres in the country. It’s very critical that we preserve these institutional spaces and that we do it with care and mindfulness.”

She also noted that the lengthy transition has helped avoid some of the pitfalls of Founder Syndrome.

“Any time a founder steps away from an organization that’s been built around them, there’s a great chance the organization will falter,” she conceded. “It’s been built around their strengths, their deficits.” Bellamy thinks the five-year handoff has helped her find her voice and learn from her father while protecting his legacy and building consensus for her vision for Penumbra.

“For some a.d.s, I think they’re just like, ‘Get out of here so I can do my thing!’” she said, laughing. “But Penumbra is so intimately tied to my father, to his legacy, I want to make sure it’s protected.”

Onstage isn’t the only place where Penumbra is going through dramatic change. “I’m not doing what I think is the traditional role of an artistic director,” Bellamy said. “I’m building out a new vision of the infrastructure here, working closely with the staff.” That’s why she hasn’t yet hired a managing director, instead beginning a planning process to explore how Penumbra can better “be a space where we can empower artists to be change-makers in their communities and support organizations with shared vision and values.” She’s also created and filled three new, unique positions: a director of inquiry, a director of advocacy, and a director of praxis. “There’s intention behind each one of those positions, but so much is going to be shaped by the people involved. I’m so excited to see what they come up with.”

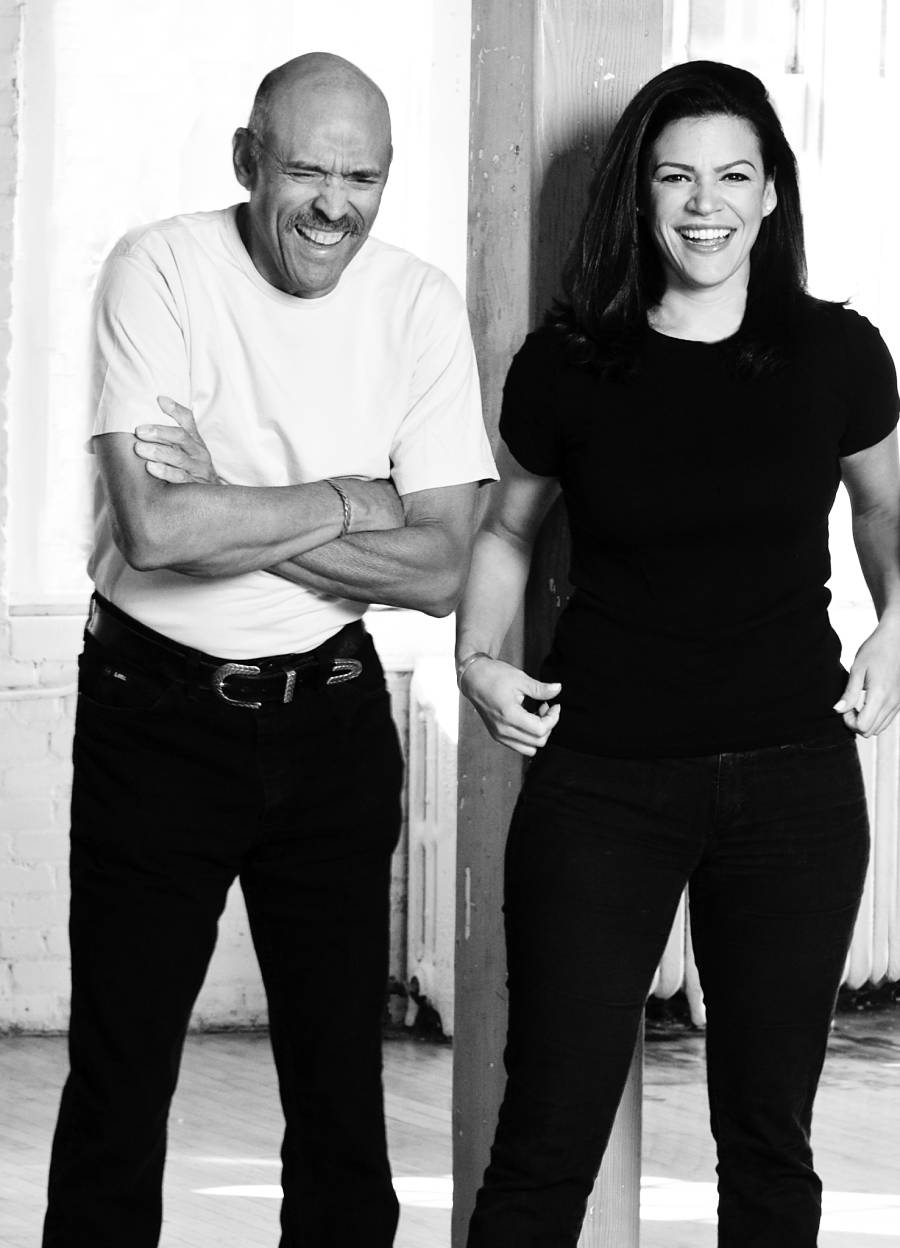

At Mu Performing Arts, a.d. Randy Reyes had a similar trajectory to Sarah Bellamy’s, having worked at the theatre for nearly a decade before taking it over. “I did outreach for them,” Reyes said. “I was the associate a.d. I was a community liaison. I took out the trash. I directed plays. I did everything.” It was actually the Guthrie that brought him to Minnesota. “Joe Dowling gave me my first job,” Reyes said. “I did several plays at the Guthrie while living in New York, then when I moved here I worked at the Guthrie as education director.”

Shortly after, he met Rick Shiomi, Mu’s founding artistic director, and the two began to work together, enabled by a two-year $70,000 grant from TCG’s New Generations: Future Leaders.

Reyes might have been the inside man, but replacing Shiomi was far from guaranteed. “As much as I wanted Rick to just say, ‘I will anoint you!’ so I could say ‘Thank you!’ and take over, we went through a national search with a committee and the board and tried to institutionalize the process.” Ultimately, Reyes sees this as a good thing, empowering the board, increasing their buy-in, and forcing him to decide if he really wanted the job and, perhaps most importantly, why he wanted it.

This idea is echoed by the consultant I spoke to for this article. “Searches work when they have integrity—when they find a person who shares the values of the organization, where they move in the broad direction that the committee, board, and organization have agreed upon, especially when it comes to the degree, nature, and pace of change.”

This kind of agreement may be easier to reach at both Mu and Penumbra in part because their missions are so specific. As Sarah Bellamy put it, “Every decision I make goes back to the mission. If it’s not mission-critical, it’s not happening at Penumbra.” Likewise, Reyes noted that Mu is “very mission-based.” Presenting work “through the Asian-American perspective…is much stronger than any kind of artistic aesthetic.”

When asked what’s changed, Reyes replied, “The biggest shift was the staff around me.” Reyes assumed the board would experience the most turnover; instead, in the two years since he took over, there has been a nearly complete change in administrative staff at Mu. “I’m trying not to take it personally,” he said, laughing. “When there’s a transition like this, everyone in the organization gets to reflect on where they are and where they want to be. It’s a good time to make those changes, a good opportunity for me to dig into what our processes and systems are, and figure out how I want to change them.”

With his new staff in place, Reyes is ready to begin building Mu’s future. When asked what he’s learned over the last two years, Reyes said, “You don’t know all that goes into running a nonprofit, particularly a theatre of color, until you’re doing it. Then you’re just amazed that it’s even able to continue.”

He cited several specific challenges for the company, all of which come back to funding: First, the granting world is, in his words, “fragile. At any time a huge funder could say, ‘We’re not giving to the arts anymore,’ and then a chunk of your budget disappears. We have to build out our donor base.” Second are the particularities of doing work by, for, and about Asian Americans in Minneapolis. “The largest population of Asian Americans here are the Hmong population,” Reyes said. “They’re a relatively new immigrant community—they’ve been here 30 years. Theatre is not a viable form of entertainment for them. Even the Asian-American people here who have money give it to the Guthrie, because it’s a status thing. We also don’t have a lot of corporate funding because we’re not that big.”

All of this has led Mu and Reyes to reexamine the company’s size. “What is the ideal size? Do we try to expand, or work within our current model—try to bring up the art and increase outreach to the community?”

Size isn’t really a question when it comes to the Guthrie; it’s the inevitable subject to which all discussion gravitates. The Guthrie is the sun around which the rest of the theatre scene orbits. “Structurally,” Alan Berks said, “the Guthrie is subsidizing the rest of the theatre here,” because it pays actors and artists under more generous union contracts than other companies.

But since the opening of its new building in 2006, the relationship between the flagship theatre and the rest of the community has been fraught. The perception persists in the Twin Cities that the Guthrie doesn’t participate enough in the larger theatre community, and that its new building is a gilded cage that has led to overly conservative and insufficiently diverse programming.

The Guthrie’s new campus, which opened in the summer of 2006, has three spaces that roughly mimic the three theatres of New York City’s Lincoln Center Theater in terms of number of seats, but produce far more work per season, all in a city with less than half the population of New York. It has proven challenging to program, to say the least, and Dowling faced some controversy over his choices and ran a deficit after the 2012–’13 season. (In an exit interview with Minnesota Public Radio, he sounded most chastened about running a deficit for the first time in in his career.)

Everyone I spoke to is excited to see what Joe Haj will bring to the Guthrie in terms of vision—or maybe anxious is a better word.

“I’m really curious to see how the next two or three seasons work for him,” Marianne Combs said. “He has a reputation for doing great work that is invested in the community where his theatre lives and responds to their needs. So to see him come to a flagship theatre that has a budget 10 times the size of what he was working with before and an equally massive board of directors—he’s said it himself: It’s hard to be nimble when you’re the head of an institution like that.”

“He’s coming in with a wealth of good will,” Alan Berks said. Berks also noted how much Twin Cities theatre has changed in the 20 years since the Guthrie’s last leadership turnover, when Dowling took over from Garland Wright (in a reportedly chilly transition). Berks credited the Legacy Amendment, a Minnesota initiative which sets aside a portion of sales tax revenue for funding the arts, for helping to create a more stable environment allowing for greater artistic risk. “Nothing’s perfect, of course, but there’s more money available, a good collaborative relationship between foundations and theatres, and a lot of forward-looking people.”

Few people are as excited—and, yes, anxious—about Haj’s future as Haj himself.

“A vision, if it’s a good one, has to include the goals and dreams of the community and the people inside the building,” Haj said. “No one is interested in being a satellite to my own genius. Nobody cares! There’d be nothing sillier than my landing in Minneapolis and saying, ‘This is what we’re doing from now on.’ A vision for the future of the Guthrie must include the hopes, the dreams, the aspirations of those who are devoting their lives to the success of the place.”

To that end, Haj views the work ahead as largely listening to Guthrie employees, community leaders, local artists, and others to develop a plan for the future. Haj knows what his broad goals are, though.

“We have to figure out how to make the very best art we know how to make, and how to connect that art as meaningfully as possible to the community we are charged to serve,” Haj said. “I don’t know how to do that yet, but it needs to be done.”

When asked about the diversity question, and about people’s fears that the size of the Guthrie campus constrains risk-taking, Haj was firm.

“Yes, there are two large spaces. If we think because they’re large, that’s our reason for putting on non-diverse plays in those rooms, that’s an unacceptable answer to me. We have to figure out how to make diverse work in those spaces.”

Still, Haj feels that this goal must be balanced with a sense of honoring the past. “The Guthrie is a classics theatre in its DNA,” Haj said, noting that founder Tyrone Guthrie wondered if Death of a Salesman was enough of a classic for the Guthrie’s first season. “We’re talking about the American canon and the Western European canon. Those are two areas of theatrical work that have largely been dominated by white men. There have been notable exceptions, including Alice Childress’s Trouble in Mind, which we’re producing this season. But I don’t think the Guthrie should stop making Molière, Shaw, and Chekhov.”

Haj feels that rather than discard the classics, the key is to interpret them with a diverse pool of actors, directors, and designers. “Who gets to tell the story? Who gets to frame the story? That becomes really interesting to me.”

Of the recently announced Twin Cities a.d.s, Haj has spent the least time with his predecessor. He hadn’t seen Dowling’s work before taking the job, and spent just a few weeks overlapping with him before taking over on July 1. But unlike his peers, Haj has experience with succession from his time at Playmakers, where he took over from David Hammond in 2008.

“The central lesson for me in taking over Playmakers was how very difficult culture shift is. Culture change is brutalizing. It’s very hard on people. Even when the change is positive. It’s like what Hamlet says, ‘We would rather live with the ills we have than fly to others that we know not of.’ It’s hard on people. It’s hard on organizations. Even when the ideas are good.”

Haj, though he hasn’t worked with Dowling, worked at the Guthrie when it was run by the late Garland Wright. Haj performed in Genet’s The Screens, in the tetralogy of Richard II, Henry IV parts one and two, and Henry V; he was even a company member for a season.

“Garland was a profound influence on me as an artist,” Haj said. “Before I went to the Guthrie, I was just another young person out of school; after, I was an actor.”

Though he was still years away from becoming a director, let alone an artistic director, Haj recalled the buzz at the Guthrie during Wright’s prime in ways that presage his own ambitions for the theatre. “I think an awful lot about Garland and about his work as the a.d. Everybody wanted to come. Everyone wanted to work here.”

What was Wright’s secret? How did he make the Guthrie such an epicenter? Laughing, Haj said, “If any of us knew, we’d do it all the time! There was something in the artistic courage of that place. Not all the time; not every show. But there were big, ambitious events. Five-and-a-half hours of Genet; 12 hours of Shakespeare in rotating rep. There were big ideas, big in a way that galvanized a community of artists, of administrators, even the national community.”

While the future of Twin Cities theatre is unknowable, and the challenges facing it no less daunting than they are for theatres everywhere, everyone I spoke to for this article underscored how excited they are about the possibilities ahead. In voicing his desire for Minneapolis to engage more with the national theatre field, Berks said, “I think some of the artists here that no one outside of Minneapolis knows are some of the best artists I’ve ever worked with. We’re doing a lot of work that’s at the forefront of national conversations about new work, incorporating artists of color” and embracing new audiences.

For her part, Combs said that Minneapolis theatre is far more integrated into the city’s daily life than in other cities. “Theatre is engaged with our communities, and it’s not just middle-class white communities,” she said, citing Mu, Mixed Blood, Penumbra, Teatro Pueblo, Pangea World Theatre, and New Native Theater. “They’re trying to reach out to various communities and represent them in ways that haven’t been done before. It’s a very exciting time for theatre in the Twin Cities, and it’s really a great time to be a reporter covering it.”

The new artistic directors echo the excitement. Reyes said that among his cohort “there seems to be a sense of sharing ideas, sharing resources. I think that’s the future, rather than, ‘This is ours, we’re doing our work and keeping our stuff, leave us alone.’” Bellamy added, “The sea-change is really exciting for a lot of us, because it’s new voices and new vision. But the other piece that I’ve been watching is how much there’s a real care and concern for the legacy of the founders.”

Making room for both the passion of the new and the wisdom of the old? Sounds like an ideal way to frame a transition.