Mention the oft-snowy northeastern city of Rochester, N.Y., to your average person in passing and they might think: home of Kodak, locale of several well-known universities. They’re probably less likely to think of it as a stop on the Mississippi Blues Trail—but this summer, a marker on that historic route will be unveiled in the Rochester neighborhood of Corn Hill. That’s because Corn Hill is where singer and guitarist Eddie James “Son” House Jr., a seminal influence on blues legends Muddy Waters and Robert Johnson, spent 20 years of his life.

Even many blues fans don’t know about it, but it’s a beloved bit of local lore most Rochesterians haven’t forgotten. This Aug. 26–29, the area’s leading resident theatre company, Geva Theatre Center, will launch a four-day event to celebrate the life and legacy of the highly regarded musician. The event will include film footage of House, art exhibits, and blues demonstrations and workshops with national and local musicians, and will culminate with a reading of Revival: The Resurrection of Son House, a world-premiere play commissioned specifically for the event from playwright Keith Glover.

The idea for the event began at a backyard potluck more than five years ago, when a handful of Geva staff and local musicians started brainstorming about ways to celebrate the legendary Rochester resident. Skip Greer, Geva’s director of education and an artist-in-residence, was one of the plan’s proponents; not long after, Jenni Werner joined Geva as its literary director and resident dramaturg, and he enlisted her as his partner in the project.

The deal was sealed in December ’13, when Geva received a $100,000 Cultural Creative Collision grant from the Rochester-based Max and Marian Farash Charitable Foundation to create the project. Now almost 100 people, counting Geva staff and community partnerships, are involved in its development.

“When we approach people who do know Son’s name, they get so excited about this project,” said Greer. “If they don’t know it, and we take them through the storytelling process, and then they get excited. It’s like a manifestation of that backyard party.”

The four-day event is titled “Journey to the Son,” and the name could also describe the process behind the project. Greer and Werner began doing immersive research last year by getting on a plane and heading in search of House’s origins.

To create a sense of place artistically, you first have to understand the place. That’s what led Greer and Werner to travel south. “We were trying to figure out where all of this is coming from—and, well, we sure learned a lot,” said Greer. He and Werner flew to Memphis, rented a car, and traveled to see several of the Mississippi Blues Trail markers. As the temperature swelled above 100 degrees, the pair headed to Clarksdale, Miss., not far from House’s birthplace in Lyon, and visited Parchman Farm penitentiary, where House was imprisoned after he allegedly killed a man in a juke joint. They talked with musicians at Morgan Freeman’s Ground Zero Blues Club in Clarksdale.

“Driving around the landscape, you can’t help but feel the oppression of the heat and what the oppression of racism would have been like for him then,” Werner speculated. “Clarksdale gave birth to so many amazing musicians—there’s something in the water there, something in the air, that has forged this.”

One longstanding blues myth tells the story of Robert Johnson selling his soul to the devil so he could learn how to play guitar. It happened at a place called the “crossroads,” and if legend is to be believed, only an actual blues musician can find that place to this day. So Greer and Werner enlisted a musician to lead them to the purported crossroads, where they did the only thing that seemed fitting: They poured some Jack Daniel’s whiskey onto the dry earth. “We gave an offering,” said Werner, who remembers that the spiked mud was caked on her sandals for days. Greer still has a little bottle of mud on his desk from the trip.

From there, the pair drove to New Orleans, where they met up with Glover, who’s based in Los Angeles, and visited the home where House spent his formative teenage years. It’s Glover’s second time working with the Geva crew—in 1999, the theatre produced Thunder Knocking on the Door, a “bluesical” for which Glover wrote the book (music is by Grammy winner Keb’ Mo’). Glover is the son of a blues musician himself, so he knows the territory. “You can hear it when he talks,” said Werner. “He understands the world in which Son House lived.”

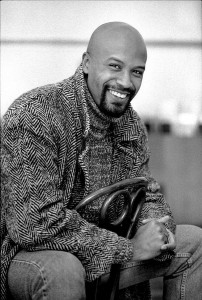

For his part, Glover, who is a member of New Dramatists and a past Pew Charitable Fellowship grant recipient, was intrigued by the project but remained skeptical at first. “I didn’t know if it was a good fit for me,” he said. “As an artist, I’m not driven to plays or subjects that I have an answer to, because that leads to something that’s really dead—you know, like, ‘Are you against racism?’ Everybody says yes.” When the three met up in New Orleans, though, Glover immediately knew the project was potentially much deeper, darker and more rewarding than he suspected.

The “father of the Delta blues,” as Son House is sometimes known, was born into a world where one couldn’t preach the gospel and play the blues at the same time. “Son House was a preacher. His father was a preacher,” said Greer. “He was a preacher who fought a battle inside of himself, because blues music was the devil’s music.”

It would be House’s lifelong struggle. He occupied the pulpit he inherited from his father until he was 25, then hit the road and recorded at Paramount Records in 1930. House was also an alcoholic who could quickly turn into a raging alcoholic.

“He was involved in the killing of two men and was married five times (not all officially). And when you go back and look at everything that feels like a stereotype of the blues—all of those things in the mythos of what the blues are—they’re his life,” emphasized Greer. “They weren’t stereotypes when he was living them—they are now because they’ve been passed on down through the ages.”

By contrast, House’s time in upstate New York was a relatively quiet period in his tumultuous life. After retiring from the blues in the 1940s, he lived in the Corn Hill neighborhood of Rochester and worked as a railroad porter; by night he nursed a bottle. He was a son of the South, yet in Rochester, he was hiding from his love for the blues and his talent, and the guilt gnawed at him each time he held a guitar. Still, House knew he couldn’t stand in the pulpit and stand on the stage—it was one or the other, so for 20 years he chose neither.

Then, in 1964, three young, avid white blues fans and record collectors—Dick Waterman, Nick Perls and Phil Spiro—found House in Rochester and convinced him to start playing publicly again. Alcohol was reportedly the only form of bribery that would coax House onstage, but once he was there he played with all his might. Films from the time show a scrawny, desperate man with wild eyes—eyes that close tight as his body gyrates to the music and his hands dart up and down the bottleneck guitar. Waterman, who became House’s manager, effectively resuscitated his career until 1974. Then, in 1976, House moved to Detroit, where he lived for the last 12 years of his life.

Aside from his railroad job and a marriage, not much was known about House’s quiet life in Rochester until Daniel Beaumont, a University of Rochester professor, published Preachin’ the Blues: The Life and Times of Son House in 2011. The book filled in some of the blanks, and served as one of Glover’s primary sources as he began his own research for the play.

“I don’t think it’s a play for the blues cats to hang out and figure out what kind of guitar Son was playing,” said Glover. “His music was asking questions, opening doors to bigger emotions. Sure, the kind of guitar is very important to that sound, but Son’s guitar didn’t matter. It’s about Africa, spirituality—it’s elemental.”

There’s a weight, a responsibility, that comes with writing on such a powerful subject, and that’s not something Glover takes lightly. “This is a subject that people know a little about, but you can’t become precious with it, especially with Son—there’s so much there. There are many different Sons.”

Glover’s commission is not part of the Farash Foundation grant for the event but something that Geva is financing separately, in the hopes of developing it beyond a reading into a play with a future. “We would be thrilled if an incredible play came out of this and Son House became a well-known blues name to more than just people who know the blues,” said Greer. “We’re hoping this play will help spread the word of the legacy of the man.”

Werner added that she hopes the play will help Geva continue a dialogue not only about Son House but “about what Rochester means, and how we can play a part in telling the story of Rochester—and in this case, particularly of the blues in Rochester,” she said. “We’re storytellers, and we want to continue telling the story and connecting with our community as we tell it.”

As for Glover, he does have a slight disclaimer for the script. “All the mistakes are mine,” he said, “and all the good stuff is Son’s.”

Leah Stacy is a born-and-bred Rochesterian, a communications and media professor, and a member of the American Theatre Critics Association.