Nobody tells a story more engagingly than a puppet.

That sounds like a foolish overstatement, right? But reflect a moment on how frequently you encounter puppets—in plays and performances, on television and in other media, in toy stores and schools, in advertising and art, in religious celebrations, occasionally on street corners. Then consider what’s involved in the theatrical transaction between an inanimate performer and the human spectator—not only a walloping dose of suspension of disbelief, to accommodate the illusion of the puppet’s autonomy and sentience, but (if you remember that Hegel essay you once had to read) the even more basic artistic transaction of extracting subjective meaning from an object, an entity that exists outside oneself. Not only are puppets good at telling stories—they deliver their narratives with an implicit dose of metaphysical speculation.

But let’s not get all pedantic here: The biggest reason puppets are so ubiquitous—and have been headliners in the theatre from ancient times (they showed up, scholars estimate, around 3000 B.C.) to now (try getting a ticket to Hand to God on Broadway)—is that they’re irresistible fun.

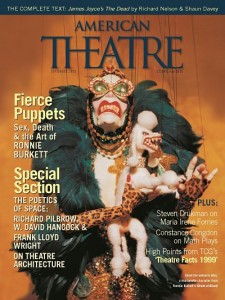

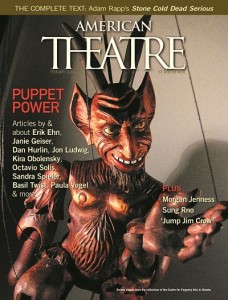

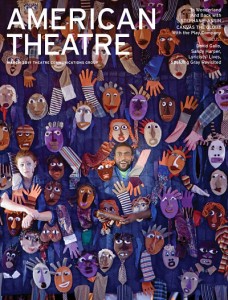

That’s justification enough for this month’s feature essay, by longtime contributor Scott T. Cummings, about the contemporary state of puppetry, based on his recent visits to Chicago and Edinburgh, where puppets have been breaking new boundaries of performance. Cummings’s enthusiasm for his subject prompted me to browse through shelves of past issue’s to see just how often we’ve given puppets top billing. Below are three recent AT covers, spotlighting such peerless purveyors of puppetry as Florida’s PlayGround Theatre (since renamed Miami Theatre Center) (March ’11), Atlanta’s Center for Puppetry Arts (Feb. ’04), and Canadian marionette master Ronnie Burkett (Sept. ’00).

The final paragraphs of Cummings’s wide-ranging piece take a particularly interesting tack, aligning the ancient art of puppetry with our contemporary avant-garde. Puppets are “a valuable element of this experimental tradition,” he posits, singling out (among a virtual who’s-who of world puppeteers) the still-evolving work of such American masters of the form as Lee Breuer, Basil Twist, and Janie Geiser. It’s a fair bet that what Cummings calls “the current puppet moment” will stretch far into the theatrical future.