Lynn Nottage isn’t on a mission to save the world. But as a sensitive and engaged citizen and human being, occasionally she feels one of the world’s myriad problems crying out for action—and, since she’s a playwright, that usually means a play.

In the fall of 2011, she had just returned to her Brooklyn home from Africa, where Ruined—her Pulitzer Prize-winning play about rape as a weapon of war in the Congo, which she’d written after first visiting Africa in 2007—had just been staged in various countries for the first time. In her inbox was a heartbreaking email from a close friend in New York who was broke—and then Occupy Wall Street happened. Nottage says she started to feel “something more needed to be done. I didn’t fully understand how we had gotten to that situation. I could read all the books, but I’m someone who likes to be in the sandbox.”

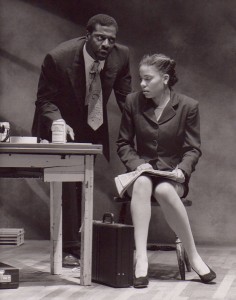

Her urge to get to the bottom of what she now sees as America’s “de-industrial revolution” coincided with a commission from Oregon Shakespeare Festival’s American Revolutions program. The play that emerged, Sweat, will be staged at the festival in Ashland July 29-Oct. 31, prior to a run at Washington, D.C.’s Arena Stage next spring and a subsequent bow in New York. Like Ruined, Sweat will be directed by longtime colleague Kate Whoriskey; and like that play, it is the result of extensive on-the-ground interviews, conducted with the help of a team. But instead of war-torn Africa, the research for Sweat was conducted just a few hours’ drive away, in Reading, Pa., which was ranked the nation’s poorest city in 2012.

“I found it really fascinating that one of the poorest cities was in the Northeast, because we usually think of the Rust Belt, we think of the South, but this poverty is so close to us,” Nottage says. The people of this depressed former steel and textile town at first felt quite far from her: Reading (pronounced “redding”) is home to a lot of white supremacists, if swastika and Iron Cross tattoos are any guide. But sitting in a room with these unemployed men, Nottage says, “What surprised me was my ability to empathize with people who I always thought were on the other side of the divide. When you interview black and Latino folks, there is a narrative that has existed for the last 50 years of being sort of disaffected from the culture. But I sat in rooms with middle-aged white men and heard them speaking like young black men in America—they feel disenfranchised, disaffected.”

Sweat follows two generations of employees at Olstead’s, a local plant that begins to lay off workers in 2000, in the wake of NAFTA, and by 2008 has all but shut down. The downturn frays friendships along generational and racial lines and irrevocable violence erupts. But the play isn’t the only outgrowth of what Nottage calls her “Reading Project”: She’s just as excited to tout a Beuys-like “social sculpture” she’s been developing with New York’s Labyrinth Theater Company, slated to go up in Reading next spring.

“I felt like a carpetbagger going in, taking the stories and then leaving,” confesses Nottage. “So we decided to build an interactive installation. It really came out of what I felt was a need for the community to be in dialogue—for their real desperation to have some sort of artistic home for ideas.”

In a recent conversation near her longtime home in Brooklyn, Nottage spoke about her work, her process, and the permission to write what she wants.

Sweat is set fairly recently…

In 2000 and 2008.

But it’s part of Oregon Shakes’s “American Revolutions” commissioning project, which is about significant points in American history. What you’re writing about is just barely history.

When Oregon Shakes first came around, they said, “Figure out what are the pivotal moments you want to address.” They wanted us to write big plays about American history. The revolution I’m looking at is the “de-industrial” revolution, which is one of the great revolutions in American history, and I was thinking: By the time I write this play it will be history. I think it’s one of the more pivotal moments; I do think it’s going to be a moment that will impact the next 100 years.

How did that lead you to Reading?

Some time in October 2011, I returned from traveling around Africa where they were doing productions of Ruined; I arrived very late at night, and I’d gotten an email from a very close friend of mine who happened to be a neighbor and a mother of two. She had sent a confidential email to about six of us saying, “You guys probably don’t realize this, but I’m completely broke, I’ve been broke for the last six months and really living on the edge, from hand to mouth, and it’s not that I’m asking for anything other than that I feel my close friends should know what state I’m in. It would just be helpful to finally share this with someone.” I read it and it completely broke my heart; it devastated me. This was during the time when there was this tremendous economic downturn. It also happened to be the same week that Occupy Wall Street was just beginning.

I said to her, “I’m sorry, I don’t know what to offer you, but Occupy Wall Street is beginning this week. Why don’t we just go down there and figure out what it is? Because you’re dealing with a lot of the same issues they’re raising.” So we went and sat in Zuccotti Park before it became this massive tent city; we sort of marched in a circle for a while and banged on drums and chanted. At the end of the day, she was like, “You know, I don’t know what I’ve accomplished, but I actually feel a little better. I don’t feel so alone in my circumstances.” We continued to sort of engage with Occupy Wall Street, but I quickly realized that something more needed to be done. I didn’t fully understand how we had gotten to that situation. I could read all the books, but I’m someone who likes to be in the sandbox—I like to know what it is that’s happening.

So I set about in December to find a city that I felt was a microcosm of what was happening in America. And because I live in New York, I thought, Let me find a city that’s within driving distance. The New York Times had written an article about Reading, which was then designated as the poorest city in all of America. I found it really fascinating that one of the poorest cities was in the Northeast, because we usually think of the Rust Belt, we think of the South. But the poverty is so close to us. In fact, six of the poorest cities in America were in the Northeast, in New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania. I thought: We have a warped perception of what poverty is.

In January 2012, began traveling to Reading with a small team of people, just to figure out, what is the demographic of this city, what is the narrative of this city? It also coincided with the first election of an African-American mayor in the town, which I thought was kind of interesting. It’s like Obama: When things are really bad, everyone feels like, “Finally! You can inherit the mess.”

Like that Onion piece about Obama’s election, “Black Man Given Nation’s Worst Job.”

That’s what it felt like. So we began trying to interview everyone, from legislators to the police force to social services to people on the street. It’s what we did with Ruined; we sort of went and immersed ourselves, and we ended up going back and forth and establishing some very close ties with the people in the town, with some of the people in social services, with some of the homeless people, with some of the people in the arts community.

Was Reading a steel town?

It was a steel town and a textile town. And it was a town that invented the outlet mall, because they had all these textile companies and they built these outlets around them to cater to consumers who wanted to buy discounted clothing. As late as the late ’80s, early ’90s, you could take a bus from Port Authority that would take you directly to the outlet malls in Reading, shop all day. It was a tourist economy, and really robust.

And it’s not there anymore?

No. They still have a big mall in Wyomissing, but the Reading malls are all gone.

So what does poverty look like there?

I think there have been two tiers of poverty. There were massive layoffs right after NAFTA, which is the period I’m looking at, which is around 2000. And 2008 was another big wave of layoffs, where a lot of the steel and textile industry moved out of the state. Some of the factories moved further south—to North Carolina, to some right-to-work states. Some of them moved down to Mexico. But there were massive layoffs. And you had this huge swath of working-class white folks who for two or three generations made really good livings—they were solidly middle-class, in union jobs—who suddenly found themselves out of work.

And then Reading had always been a town that attracted labor, so you had waves of immigrants: Dutch, Italian, Polish. In the ’50s and ’60s, Puerto Ricans began coming. Most recently it’s Dominicans, who came with the assumption that there would be employment and cheap housing stock, but they got there just as the economy crashed. So that’s what the other side of the poverty looks like: You have a very large Latino population that has no place to go and no place to work.

So how did you get from that research to the play?

I call it my Reading Project, and there are two distinct branches of it. One is this play I became really interested in writing, which was just looking at a group of friends who find themselves laid off, and how it affects their lives over the course of two generations. That’s what Sweat is. And then the other side of this, because we became so attached to Reading and I felt like I was a carpetbagger sort of going in, poaching, taking the stories and then leaving, we began working with the city to figure out what kind of art could we create that could stay here and could put the community in dialogue. We really wanted there to be sort of a social mission. We began to talk a lot about sort of Joseph Beuys-like social sculpture putting community and art and activism together into one space. I think we’ve narrowed it down to this huge supermarket that we’re going to build it in, and we decided to build an interactive installation.

When will that be?

Probably in spring of 2016. Pennsylvania is a swing state, and we wanted to put out Sweat just before the election. These are the conversations we should be having, and I feel like as artists we should be socially engaged, and that at times we can be strategic in the ways we engage audiences. We’re going to Washington next year, to Arena Stage. We discussed, What is a good time for it to go? Next year.

When you do source interviews, as you’ve done for two plays now, how do you process what you take in? Do you immerse yourself in the research, then walk away and write the play?

That’s usually my process: Sit down, experience it in the moment, then push it aside. Just feel the energy in the space in the moment, and then interpret that and make it into a piece of art. I’m not as interested in absolute verisimilitude, in replicating those moments and those interviews, as sort of capturing the essence of what I experienced in the room, and the essence of those individuals.

How would you describe that essence in Reading?

Reading has been through an incredibly hard time. There was a level in some rooms of desperation, of profound sadness. In some rooms you could feel the nostalgia for what was and the longing for that to return. I think in some cases, there was genuine confusion: like, we signed with a contract with America, these were the things we were supposed to be received, and somehow we were lied to. So I think that people felt betrayed.

What surprised you the most in Reading?

It’s part of the reason I wrote Sweat. What surprised me was my ability to empathize with people who I always thought were on the “other side” of the divide. So often when you sit in a room and interview black and Latino folks, there is a narrative that has existed for the last 50 years of being sort of disaffected from the culture. But I sat in rooms with middle-aged white men and heard them speaking like young black men in America—they feel disenfranchised, disaffected.

Did you emerge feeling hopeful or despairing about the situation there?

I always told people when I first went to Reading that I went with the desire of finding stories of resilience and resurrection, because that’s really important to me—I don’t want to just sort of show poverty porn. I’m turned off by that; it’s not the kind of art I wanna engage with. But when I arrived, those stories [of resilience] were few and far between. There’s one guy in particular, a really dynamic African-American leader who’d been to prison, gotten out, got his Ph.D., was teaching at the university, had organized green markets, organized a group of young entrepreneurs and thinkers to be the next generation of leaders in Reading. For two years he really was one of our spiritual guides there. And then at some point, we had lunch and he said, “I have to tell you, I’m leaving Reading.” And I said, “What do you mean you’re leaving Reading? You’re my story, you’re my happy ending!” He was like, “You know, I’ve worked really hard, but I met a woman and this is not the way we want to raise our children. We’re gonna move to Philadelphia. We just want a better life.” And I thought, if someone like him is leaving, it makes me feel very sad for the future of the town, because he was one of the shining stars.

What’s Reading like just to visit?

One of our first times there, we had gotten lost and had stopped at a gas station, and this car pulled up, and the guy says, “You guys don’t look like you’re from around here. Can I give you a piece of advice? Get out before sundown.” It made us laugh so hard. He was so dramatic. The next time we went, our car was broken into.

Did it make you laugh because you’d been to wartorn Africa, and how bad could Reading be?

Well, Reading is a little scary. We went into this local bar; we decided, “Let’s go at night, let’s just see what he’s talking about, just visit a couple of spots.” We walked into this bar and we literally stopped, like there was a force field, because we were so scared. There was rough trade in there. Someone was snorting cocaine on the table. It was six o’clock at night and people were already completely shit-faced. We immediately backed out and laughed about it; we went and had a drink somewhere else.

One of the problems that Reading faces is that, because for so long it was this industrial giant, a lot of the social services offices in Pennsylvania are based there; when a guy comes out of prison, he could go to the corner and get a job the next day. The problem is, the jobs dried up, but all of those services are still right there in Reading. So when guys get released from prison, they go there. It’s like a dumping ground for people coming out of prison. Which seems very wrong; you’re putting people in a position to fail immediately.

I realize I’ve seen or read most of your plays, and Sweat may be one of the few I can think of where you’re dealing with a contemporary American subject.

Well, there’s also Fabulation and Por’Knockers. But those plays tend not to be as popular.

I guess my point is: You’ve made the world your canvas and written about whatever period or place drew your interest. You’re not writing your “family play” over and over.

I’m not doing a cycle. And I haven’t yet, but I’d like to write a family drama.

Many writers start with that—their family play, their own experience.

I always write about my experience; it’s just told through metaphor.

Did you always have the confidence to just write about whatever you wanted, or did you feel that someone needed to give you that permission?

I don’t think that I was given permission; I just feel like I follow where my imagination goes. I think I’m restless. And I think the restlessness is manifest in the work. I like to wander; I’ve always liked to wander, from the time I was very young. I like to travel to different places; I like to see different landscapes. I think that that’s just sort of flowed into my work.

I remember you telling me that you started writing By the Way, Meet Vera Stark as a diversion after the heaviness of Ruined. I have to admit: When I read Vera Stark, on the page I didn’t get how funny it is.

How did you not get that it was funny? It’s all parody.

The joke was on me! But when I saw it at Second Stage, I got it and loved it. Now it seems to be done a lot of places.

Not really. Comedies don’t get done as much. They just don’t. Intimate Apparel—that’s the workhorse. Ruined doesn’t come up at all.

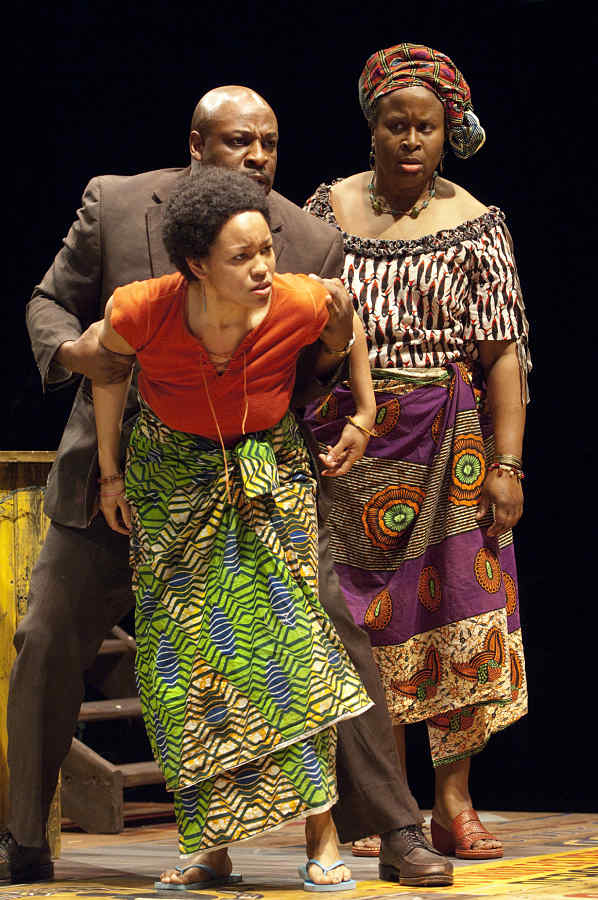

Did you see the Oregon Shakespeare Festival production of Ruined that Liesl Tommy directed?

I really liked that.

I feel like that avenue staging really put you there.

Did you hear the story about what happened? It’s become sort of famous in Oregon. One of the soldiers, as he was sort of going for the women, someone jumped out of the audience and hopped on his back and wrestled him down.

Wow!

He had to fight them off. He was really shaken up by this. I wasn’t there, so I don’t even know which scene it was.

It reminds me of a story Gordon Davidson once told about Zoot Suit, that during a fight onstage between the cops and the Pachucos, someone jumped up onstage to join the fray.

Yeah, I thought, “Good. It worked!” But it freaked the actor out completely, because there was physical contact.

I wonder what was going through that person’s head.

She wanted to stop it, like, “I can’t take it!” People are right there.

Had you had any dealings with Oregon Shakes before then?

I’m told I am the most produced living playwright at the festival. [She’s actually tied with Robert Schenkkan. – Ed.]

I need to ask about the future of Ruined. Is there still talk about it going to Broadway or being a movie?

No. You know, it’s there. People still ask me, but I also feel like now is not the moment for it to be on Broadway. There’s still a part of me that feels like a commercial production about the lives of those women somehow doesn’t rest well. That’s just me. I would love more people to see it, but I don’t want people to pay $150 to do that.

I guess there is something weird about that.

There is something weird about it, and it makes me very uncomfortable. I think it would have been different if, in its organic life coming out of Manhattan Theatre Club, there was still that momentum because people really wanted to see it—fine. But I feel like, to remount it now, and can we get big enough stars to do it? That’s not what I’m interested in it. Nor do I think Broadway should always be the endgame. In thinking about Sweat: Why can’t the endgame be this social sculpture we’re doing in Reading? One of the things we’re looking at is, Why can’t it be theatre that goes outside the proscenium?

I always tell my students, The problem is that you have all these institutions that have invested in buildings that are very expensive and have to be maintained, and they have to have something to put on their stage and to feed the desires of their subscribers, and as a result they’re selecting work that is popular enough to sell tickets. Which means that writers are creating work to get produced. And I’m like, What if you stopped thinking that way? Theatre today doesn’t have to exist in the proscenium anymore.

Vera Stark would be good on Broadway, though, as a kind of boulevard comedy.

Yeah, Vera Stark is designed for that. We did talk about it, and one of the things Carole [Rothman, at Second Stage] has said is, Wouldn’t it be great if we had the space on Broadway to move it to? Vera Stark would have been one of those plays, because it was selling exceptionally well. We could have just moved it right into a Broadway house and it could have had a life.

But I feel like Broadway’s always been dangled as that carrot that we should be moving toward, and as an artist, that’s not the place I imagine my work ending.

I’ve read that you’re working on a musical.

I am—an adaptation of Black Orpheus with George C. Wolfe. The music exists; we’re going to use a lot of catalogue music.

That’s headed for Broadway, right?

Well, we’ll see.

If it’s a musical with George C. Wolfe…

Yeah, then it’s probably Broadway. And I’m doing an adaptation of The Secret Life of Bees with Duncan Sheik and Susan Birkenhead.

That sounds fun.

It is fun. And then my big thing is the opera that was commissioned through the Metropolitan Opera and Lincoln Center Theater, an adaptation of Intimate Apparel with Ricky Ian Gordon, which we’re halfway through. He approached me some years ago and was like, “I really wanna write an opera with you,” and we spent two years listening to music and talking about what to write, and finally he said, “What about Intimate Apparel?” I was like, “Oh my God, I’ve been thinking the same thing, I just didn’t wanna say it.” Both of us wanted to do that but neither of us said it for a while. We could have saved a lot of time! It is operatic; its perfect form, I think, is an opera.

Are you working on anything for film or television?

No, I’m too busy. Increasingly I feel apologetic about that.

You don’t need to apologize for that!

I know—I just feel so much pressure to do it. And I thought, What if I don’t want to?

I know some playwrights who make a living from commissions and productions and teaching who think: I may write for TV some day, but while I can, I’ll write my body of work for the stage—make hay while the sun shines.

That’s how I kind of feel. Television is a huge time suck. Some people can job in and do a couple episodes, but you have to sort of commit to doing it for six months, and be in a writer’s room. Maybe when my son is older and my daughter’s in college. Of course, I say that as I’m about to leave for Oregon for two months.

The last thing I want to ask you about is: What was Ruined like in Africa?

I had two experiences that were very different. They did it Kinshasa, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, in a production that made me very unhappy. The director and the cast were beautiful people, but he comes from an auteur culture, they trained in France, so he took some liberties with the piece that absolutely drove me insane. At the very end I was literally speechless. I sat through this four-and-a-half-hour production of the show, and saw one of the most astonishing things I’ve ever seen. There’s a scene where the women are being raped, and they wreck the bar. These actors actually spent 20 to 25 minutes completely dismantling and breaking bottles; they broke the refrigerator to pieces, tore the hinges out, they broke every single piece of furniture on the stage. At some point, I thought, Are they lost in the moment? Did the director plan this? Because I don’t remember it from rehearsal. The director then decided that he was going to have the women come out in wedding dresses, bathed in this red light, and they were being sprayed by a firehose. I’m just like: Oh my God. It was totally insane.

The other experience was in Chad. It was a small theatre company, which actually produced a very lovely production, very contained and very respectful. They stuck to the script. The most moving thing about that production was that in Chad, women who are artists are considered to be prostitutes, so you find very few women who sing, who write, who paint. So these incredible women who are theatre artists were risking their lives to tell the stories, and this theatre company was run by a woman who played Mama Nadi who was fantastic in it.

But there was a guy who was the only bad actor in the play. He was playing Mr. Harare. He was just terrible; every time he came onstage, I was like, “Ach, God, why’d they cast him?” A couple of days after, this guy found me at this party and he’s like, “Do you want to know why I was in your play? My daughter was part of a theatre company, and they traveled up north to do agitprop about AIDS and public health.” He said that her company, after they did this piece, were set upon, beaten, and raped by the police. They went to the local officials to find some sort of justice and could find none. He said, “I did your play to stand in solidarity with my daughter.” And I thought, Thank you—that’s so powerful. He was saying: “I’m going to take the chance, I’m going to stand on this stage and say…” [Verklempt.]

That made up for his bad performance.

Yes, but more importantly, there are places where theatre is still really vital and necessary, and can have social impact.