CLEVELAND: “Remember, politics don’t work; religion is a bit too eclectic; but art—art can be that parachute that catches us all.”

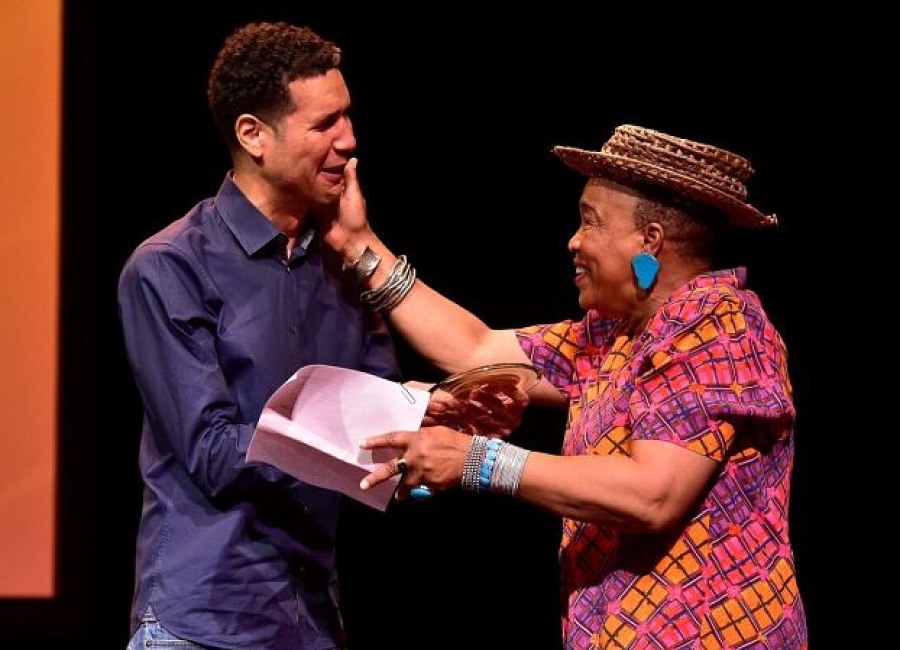

These were among the powerful words offered by Rhodessa Jones, who received the Theatre Practitioner Award on Saturday evening at the closing plenary at the 25th Theatre Communications Group National Conference in Cleveland. Jones, celebrated for her work as the co-artistic director of the San Francisco-based Cultural Odyssey and her work founding the Medea Project: Theater for Incarcerated Women, spoke with passion about the role the arts played in her life.

Her words echoed through a crowd of around 800 theatre leaders and makers who were charged, throughout three days of conference gatherings at the city’s Playhouse Square, with finding ways to change the game—whether by increasing the diversity onstage and behind the scenes, finding ways to better engage and include different communities to the theatre, or redefining what leadership means within a company.

For Will Power, playwright-in-residence at Dallas Theater Center, who presented the award, Jones was an irreplaceable part of his journey to the stage.

“When our children and our leaders and our elders are being murdered in the streets and in our churches, the immense body of work that this person has created and is creating is more vital than ever,” Power said, noting that it was a production of Jones’s Big-Butt Girls, Hard-Headed Women in a small black box in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district that led to his lifelong pursuit of theatre. “After all this time, I”m still learning from her and still saying to myself, ‘Maybe one day I can be half as good as her.’”

Accepting the award, Jones repeated, “Theatre saved my life, theatre saved my life. I still wonder, ‘Well, what does it all mean? Who is art for? And where do we all enter?’”

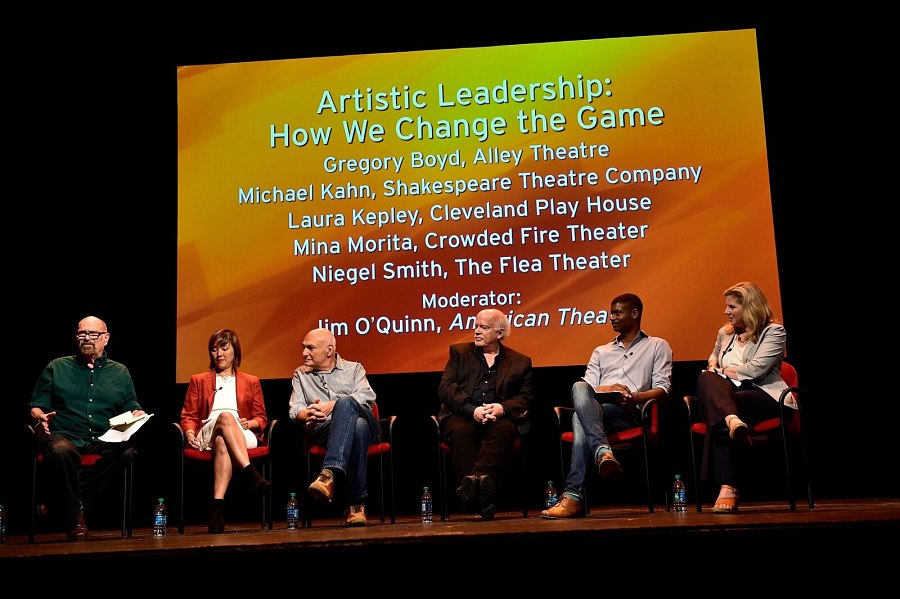

The discussion that followed expanded on those themes. American Theatre editor-in-chief Jim O’Quinn moderated a panel of artistic directors at organizations large and small: Gregory Boyd of Alley Theatre in Houston; Laura Kepley of Cleveland Play House; Michael Kahn of Shakespeare Theatre Company in Washington, D.C.; Mina Morita of Crowded Fire Theater in San Francisco; and Niegel Smith of the Flea Theater in New York City.

O’Quinn kicked off the conversation by asking Kahn about his start at the Shakespeare Theatre 29 years ago.

“I guess I’m here because I’ve been doing this all my life, and I’m a good example of how you can actually have an exciting and fulfilling and overly dramatic, crisis-ridden, thrilling existence if you stick it out,” said Kahn, alluding to the company’s historic ups and downs. “Your job is not to make a success, whatever that means…but whether you and the people you were working with were doing the best work you knew how, and find a way to address that to the community you’re in.”

The notion of community resonated throughout the conference, particularly in the audience engagement sessions, and Boyd shared that one of the defining moments in his career was when he observed William Ball lead American Conservatory Theater in the 1960s and ’70s. Boyd emphasized the importance of creating work for specific companies, both for the artists’ development and security as well as to instill ownership of the work in the local audience.

“A traveling actor said to me, ‘We always talk about artistic home, artistic home—what does that mean?’” Boyd said. “For a home to have a set of siblings for eight weeks and another set of siblings for eight weeks, it’s not a home—it’s a halfway house.”

Boyd went on the say that the reason an acting company is an important model is so when more challenging work crosses the stage, the audience trusts the artists presenting it and feel ready for the journey. “I don’t know if it’s a game change,” he said. “That’s what the game was, and I think we need to get back to that.

“Why are we afraid of risky or edgy work?” Boyd said later in the session. “Nothing worthwhile is embarked on without fear. I hope for myself that I’m scared half to death all the time.”

Unlike Boyd and Kahn, who have each been running their theatres for more than 20 years, Smith has been on the job for just four weeks at the Flea. O’Quinn asked Smith about Willing Participant, an activist theatre movement that creates art in response to current events.

“Sometimes we have to put down that work and do what our country, what our neighbors are asking from us,” Smith said, explaining that new-play development is usually too lengthy a process to respond to headlines with sufficient speed. “We couldn’t make work that was aesthetically pleasing in a quick enough way to hit the pulse of society.”

O’Quinn also asked Smith about the Flea’s resident company the Bats, a group of young actors who have been the subject of much debate lately, as they are not being compensated. “If one of these actors is still in our institution in two years, we’ve not done our job,” Smith said, calling the company a training program for pre-professional performers.

Like Smith, Morita is also fairly new in her role at Crowded Fire; she worked previously at Berkeley Repertory Theatre. She said this was her first conference, and added, “I’m so inspired to consider that I’m not always looking for myself as I create space for the work and for diverse voices, but also looking at those who are coming into our field.”

Kepley, also a relative newcomer to her post at the helm of Cleveland Play House, said she was moved to tears both by the conference coming to her city and by the content of the discussions she was a part. She closed by both thanking and challenging the leaders in attendance.

“I think your being here will change the future of our community here in some ways, and we hope that your being here will change your future,” she said.

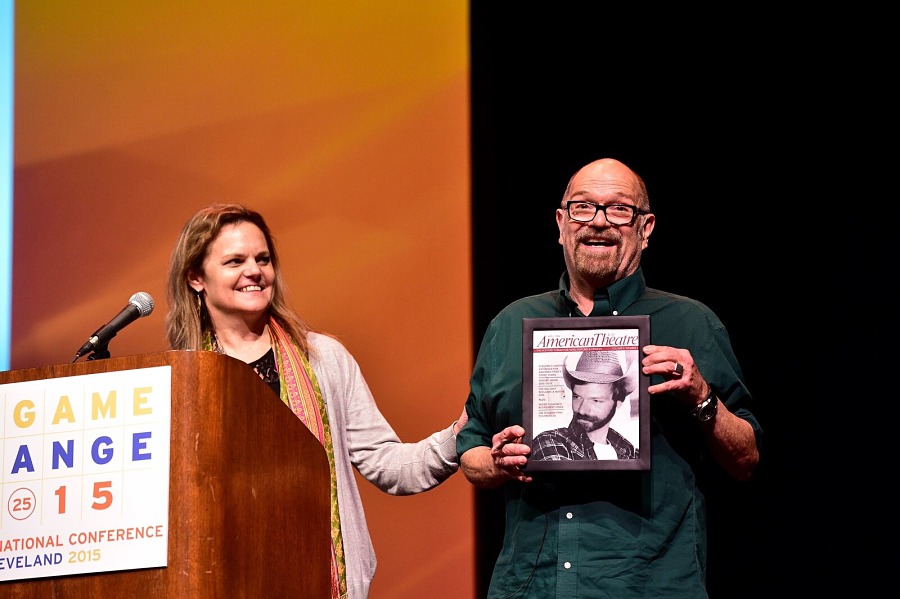

But this wasn’t the end of the plenary or the conference: TCG offered a surprise send-off to O’Quinn, who will retire from his editor-in-chief post this summer after 31 years. The Louisiana native received a fitting tribute from Lisa Mount, who walked out with her banjo and performed a familiar New Orleans classic with new words, “When Jim O’Quinn Goes Marching Out.”

TCG executive director Teresa Eyring presented O’Quinn with a Photoshopped copy of the first American Theatre cover, in which O’Quinn’s face replaced Sam Shepard’s. Said Eyring, “If theatre holds the mirror up to nature, Jim’s American Theatre has shown us our own reflection.”

In her closing remarks, Eyring recalled some of the conference’s highlights: dancing with pink elephants at the Cleveland Public Theatre, sampling local performances and restaurants, and dining at the donut truck. But she finally brought it all back home to the stage.

“The stories we tell matter, and how we tell them matters, and who gets to tell them matters,” she said. “Maybe they matter even more in theatre because the way we tell stories is through human beings.”