This essay first appeared in The Art of Governance (TCG Books), a 2005 collection edited by Nancy Roche and Jaan Whitehead.

When the American regional theatre movement took off in earnest in the early 1960s, it was traveling alongside some heady companion movements: Civil Rights, feminism, environmentalism, sexual liberation. The upstart effort to foster resident professional theatre companies in cities, towns, and communities across the nation hardly rates, on the Richter scale of social and political consequence, with those broader categories of revolutionary impulse. But a revolution it was—one more finite and focused than those larger societal movements, and with consequences that can be documented and quantified as well as debated for their impact on the art form itself.

Numbers tell part of the story.

In December 1961, when the Ford Foundation approved an initial grant of $9 million to begin “strengthening the position of resident theatre in the United States,” the term itself was newfangled and obscure; foundation staff helpfully referred in early grant documents to “what Europe knows as ‘repertory theatres.’” While an array of educational and amateur theatres kept stage activity alive outside New York City, the professional theatre landscape at the time was limited (with rare exceptions) to the Broadway commercial theatre, New York–based touring companies, and a smattering of summer stock companies. As Zelda Fichandler capsulized it: “There was Broadway and the Road.”

Fichandler was only slightly exaggerating. A few significant theatre companies with professional aspirations had put down roots in the early part of the century—the venerable Cleveland Play House opened in 1915, and Chicago’s Goodman Theatre was founded as a school in 1925—and others predated the Ford initiative by little more than a decade: most notably, Nina Vance’s Alley Theatre in Houston, founded in 1947; Margo Jones’s Theatre 47 in Dallas, launched in the same year; and Fichandler’s own Arena Stage in Washington, D.C., initially organized in 1950 as a commercial venture. A number of festival theatres (usually meaning summer seasons only) devoted to Shakespeare were also in operation, including the Oregon Shakespeare Festival in Ashland (founded in 1935), Joseph Papp’s New York Shakespeare Festival (founded in 1954) and the Old Globe in San Diego (founded in 1957). These and a handful of other professionally oriented companies were poised—alongside those hundreds of others about to be kindled into existence—to benefit from what turned out to be Ford’s visionary largesse.

The growth came fast and furious, in a kind of perfect storm—a convergence of money and legitimacy with passionate interest on the part of young theatre artists (fueled in no small part by daredevil work being done Off Broadway and the anti-establishment tenor of the times) in alternatives to the economics and aesthetics of the commercial theatre, and in new repertoires the commercial sector had ignored (the classics, cutting-edge new work, forgotten masterpieces).

The money and legitimacy were to come from Ford’s philanthropy to theatre companies, which would eventually total an astonishing $287 million. Then, to seal the case for an unprecedented national expansion of theatre art, came the establishment of a national membership support organization, Theatre Communications Group, and the founding in 1965 of the National Endowment for the Arts, the first program of designated federal subsidy for arts institutions in U.S. history.

Why was this expansion of theatre in the U.S. so essential to the viability of the art form in American cultural life? The question has any number of answers, depending on your perspective.

“The idea that artists could create a life in the theatre in Providence or Louisville was inconceivable in 1961,” pointed out Peter Zeisler, a cofounder of the movement’s exemplary institution, the landmark Guthrie Theater of Minneapolis, speaking, as he often did, as an advocate for individual artists and their creative independence. Building a theatre career before the ’60s was indeed synonymous with living in New York City; and, to the detriment of artists and audiences alike, Broadway had devolved after World War II into an upscale retailer of popular musicals and boulevard comedies, virtually devoid of the classics and equally shy of risky new plays (the occasional Miller or Williams or O’Neill excepted). From the perspective of the larger American public, theatre was geographically and economically inaccessible—and essentially off the radar.

All that was to change significantly in the first five years after Ford’s initiative was announced, as some 26 major new theatre companies (not counting burgeoning Off-Off-Broadway groups) were established in far-flung U.S. cities, large and small. Suddenly, for millions who thought of theatre as a distant and esoteric experience, live performance was becoming a local affair, an alternative to movies or television, even a bonding community experience (when theatres played their cards right). Within the same period, more Equity actors began working in not-for-profit companies than on Broadway and the road combined.

In 2005, 44 years later, the numbers are off the charts: More than 1,200 U.S. not-for-profit theatres are currently alive and more-or-less well (the number is based on TCG’s annual fiscal research, though neither TCG nor the Endowment ventures an exact count), mounting some 13,000 productions a year and having an estimated economic impact on the U.S. economy of more than $1.4 billion.

Such tallies show the enormous scale of the regional theatre movement, but its impetus can only be understood in terms of the outsized personalities who led the charge. Along with Guthrie pioneer Zeisler, who continued to spur the movement on from his post as executive director of TCG from 1972 to 1995, and the trio of visionary women whose names are attached above to theatres they inaugurated (of the Alley, the indomitable Nina Vance was fond of saying, “I clawed this theatre out of the ground”), those personalities include the man who conceived the Ford Foundation initiative that started the ball rolling: W. McNeil Lowry.

Lowry was only three-and-a-half years into what would become a distinguished 23-year career at the foundation when a new, national-scale philanthropic program in support of the arts was placed under his direction in 1957. Ford’s aim in nurturing the theatre was, in Lowry’s own words, “to offer American artists a clean slate, to encourage them to build companies devoted to process; in other words, to foster the coming together of American directors, actors, designers, playwrights and others beyond a single production and beyond commercial sanction.”

Lowry—soon to be known as “Mac” to the theatre people he advised—launched a series of field studies; staged a planning session in Cleveland in 1958 attended by such key movement personalities as stage director Alan Schneider, impresario Joseph Papp and producer Roger L. Stevens (who was destined to become the first chairman of the NEA); followed up with a landmark 1959 conference in New York, where, Lowry said, “the first planks in the resident theatre movement were laid down”; and, a year later, drafted a grant for a four-year program to establish TCG. This essential groundwork, and the continuing flow of foundation support to theatres through the ’60s and ’70s, carefully overseen by Lowry—including backing for the seminal experimental work of such groups as Joseph Chaikin’s Open Theatre and Ellen Stewart’s struggling La MaMa E.T.C., and the controversial underwriting of the creation of the Negro Ensemble Company (which led to charges from Civil Rights leaders that Ford had retreated from its integrationist policies)—gave the movement its backbone.

That backbone undergirded the network of professional resident theatres that came into being or solidified their identities during this era of proliferation—basically, the array of companies that today belong to, or aspire to the standards of, the League of Resident Theatres (LORT), the national association representing the interests of larger-budget organizations. The imprimatur of the newly formed arts endowment—and the important legislative provision that 20 percent of the NEA’s total budget was to “pass through” directly to the states, resulting in the establishment of state arts councils as well—put theatres, along with museums, symphonies and other arts organizations, on a new and more public footing.

The single event that became the most potent symbol of this simultaneous burgeoning and decentralization of the American theatre, and that defined both the movement’s dearest goals and some of its shortcomings, was the establishment of the Guthrie in Minneapolis.

While most regional theatres originated locally, carefully molded and tended by their organizers, the Guthrie (first known as the Minnesota Theater Company) sprang full-grown from its creators’ heads in 1963. Zeisler, who had been working as a Broadway stage manager, and his fellow New Yorker Oliver Rea, a scenic designer, wanted to find a hospitable American city in which to begin a regional repertory theatre devoted to the classics. They enlisted the aid of the eminent British director Tyrone Guthrie, who joined as a partner in the enterprise, and after four-and-a-half years of fundraising, planning, and meetings in seven U.S. cities, the triumvirate settled in the Twin Cities to bring forth what Guthrie called “an institution, something more permanent and more serious in aim than a commercial theatre can ever be.”

The Guthrie’s dazzling first season, with George Grizzard, Hume Cronyn, and Jessica Tandy as part of a 47-member company playing in rotating rep on designer Tanya Moiseiwitsch’s distinctive thrust stage, was greeted with national fanfare. Life magazine called it “the miracle in Minneapolis.”

“Planting the Guthrie full-blown in a Midwest landscape, for many corporate and lay patrons, gave credibility to new efforts in other communities,” wrote Lowry, whose foundation provided funds to insure the theatre against loss in its first three years. Lowry was right: The advent of the nation’s most fully realized not-for-profit professional company, complete with its own brand of Equity acting contract negotiated by the newly formed LORT, stimulated popular support for both existing institutions and for the start-up of new ones.

The Guthrie was an enduring success (as this book is being written, an expansive new $125-million complex to house the much celebrated company is under construction), but its operations over the years serve as a textbook case for the regional theatre’s thwarted ambitions as well as its accomplishments. Size matters, and the Guthrie’s vast, 1,437-seat auditorium was often hard to fill. The ideal of a permanent acting company playing in rotating repertory (one of director Guthrie’s key principles) got a great run in the company’s early years, but was unable to take permanent hold there—or, indeed, anywhere in the American theatre system, despite the best efforts of such determined rep-company advocates as William Ball, at San Francisco’s American Conservatory Theater; Robert Brustein, at Yale Repertory Theatre in New Haven, Conn., and later at American Repertory Theatre in Cambridge, Mass.; and Ellis Rabb, at his short-lived APA Phoenix in New York.

Similarly, the frequently articulated aim of developing an original, genuinely American classical acting style, free of the stiffness and histrionics of English traditions (at one extreme) and the mumbly hyper-naturalism attributed to the Method (on the other), got lost in the shuffle of artistic leadership after Tyrone Guthrie’s departure, and was pursued elsewhere only in fits and starts.

On the plus side, as Zeisler has written, “Once the Guthrie and a few other theatres started to examine the classic repertoire, actor training changed radically in this country. Suddenly, enormous physical demands were being made on actors. It became necessary to have voice work and movement work in the training programs that there’d never been before.”

Many other changes were afoot, including a concurrent and equally vital wave of theatre activity only tangentially affected by the economics and mechanics of Ford and TCG. This initiative came from artist-activists, a rich array of politicos, experimentalists, collectives, and rebels of various stripes who were less interested in theatre per se than in the proud traditions of social organizing, labor issues, and identity movements. They seized the historical moment—its freewheeling ethos, its radical sense of possibility—to put theatre to work in passionate service to their causes: racial or ethnic equality, the antiwar and antipoverty movements, gay liberation.

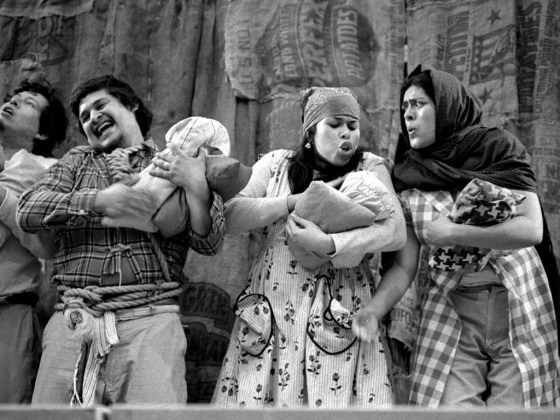

On this front, the San Francisco Mime Troupe redefined American street theatre with its sharp satires opposing the war in Vietnam; Luis Valdez, with the support of protest leader Cesar Chavez, founded El Teatro Campesino as a company dedicated to the heritage and lives of Hispanic farm workers; Bread and Puppet Theater’s peace pageants, with their craggy, monumental puppets, inspired thousands; budding experimentalists like Sam Shepard and Lanford Wilson plied their trade at Off-Off-Broadway’s Caffe Cino; John O’Neal’s Free Southern Theatre championed civil rights in the Deep South; acclaim for the Negro Ensemble Company enlivened the Black Arts movement and fostered the New Lafayette and New Federal theatres in New York City; some years later, Roadside Theater sprang up in Appalachia; and East West Players took up the cause of Asian American artists in Los Angeles. The list is as long as it is inspiring.

This mushrooming theatrical activity, grassroots and otherwise, was part of the larger arts renaissance of the era, and it fed variously upon the new energies being unleashed in the worlds of dance, literature, and the visual arts (via “happenings,” for example, and, more generally, the minimalist impulse that gave rise to what we know today as performance or performance art). Another important outgrowth of this general artistic ferment was the formation of collective theatres, alternative troupes, or, in National Endowment for the Arts parlance, circa 1984, “ongoing ensembles,” dozens of which burst onto the scene in the ’60s and ’70s, and many of which continue to endure today despite the odds against them. Such artistically original groups as New York City’s Wooster Group and Mabou Mines, northern California’s Dell’Arte International, Milwaukee’s Theatre X and the traveling Cornerstone Theater Company based their work on longstanding partnerships, democratic decision-making, and collective creation by communities of artists whose bonds were deepened by time. The NEA’s eventual addition of its IntraArts and Expansion Arts programs bolstered those who did not recognize themselves in the more traditional trappings of the theatre establishment.

The decentralization and diversification of the American theatre did change university and conservatory training for designers and directors as well as actors, much as it reconfigured the economics and the locus of the theatre business in America. The stage became tempting again to writers, as playwriting shed its esoteric status and gained prestige as a literary form; new plays, freed of the hit-or-miss constraints of the commercial system, were touted by many theatres as leading attractions.

Audiences, it goes without saying, changed and grew, as well (today’s arts advocates are fond of citing the statistic that more people now attend live performances than sporting events in the U.S.). Zeisler again: “Perhaps the most stunning thing of all—and one of which we need to constantly remind ourselves—is that the not-for-profit professional theatre was created with no precedents, no role models. It was learning to fly by the seats of many pairs of pants; textbooks didn’t exist. Has there ever been such a radical change in the form and structure of the theatre in so short a period of time?”

That rhetorical question’s answer—undoubtedly not—may be taken as both admonition and affirmation. The speed with which changes in the system occurred meant that expectations and reality were sometimes out of sync. The aforementioned ideal of permanent acting companies, for example, was abandoned for a host of reasons, artistic and economic. Such an arrangement put limitations on casting; actors were not willing to commit themselves long-term, especially in geographically isolated areas of the country; and the maintenance of full companies proved prohibitively costly.

Still, other manifestations of the company model emerged in cities like Chicago, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C., where clusters of not-for-profit theatres offered regular employment to a local talent pool, and it became possible for designers and directors to engineer satisfactory, regionally based careers as well. In the same spirit, a great success of the movement has been the affirmation and nurturing of the American playwright, not only in terms of production but of writer development.

Recent decades have seen playwriting in this country advance from the status of an adjunct literary genre to that of a viable career. Theatres in the regions have become the showcase of America’s best theatrical writing—of the past 34 winners of the Pulitzer Prize for Drama, 32 have premiered at not-for-profit companies.

As the years passed and founders of theatres inevitably turned leadership over to a new generation, the character of the work on some regional stages underwent changes. In the less charitable view, many once-vital wellsprings of theatre art grew into management-heavy institutions, supporting a vast array of artists but missing the spark of visionary intensity that was the movement’s animating impulse. While such criticism may have been valid in some places and at some times, the fact remains that the movement’s larger goal of making it possible for theatre professionals to make a living in communities throughout the nation has been by and large achieved; the regional theatre movement has provided America’s theatre workers with an “artistic home.”

Once upon a time, professional theatre in America operated centrifugally: From the creative crucible of New York City, theatre spun out, via the touring circuit or the scattered outposts of resident stages, to the nation at large. Today that dynamic is precisely reversed. Theatre in America is centripetal: Its creative fires burn in hundreds of cities and communities, and that energy flows from the regions to New York City, where the commercial sector has grown dependent upon its sprawling not-for-profit counterpart for virtually every aspect of its well-being. Broadway is still the place where talents are validated and economic prospects escalated, but it is no longer the singular, or even the primary, font of the nation’s theatrical creativity.

That distinction belongs to the array of not-for-profit professional theatres that has blossomed into being over the past 45 years in every nook and cranny of this country: the diverse, still-evolving network that must be acknowledged for what it is—America’s national theatre.

Jim O’Quinn is the founding editor of American Theatre magazine, and served as its editor-in-chief from 1984 to 2015.