Why should an international theatre festival exist in Los Angeles, a city with one of the most productive theatre scenes in the country?

The sixth annual Hollywood Fringe Festival opens on June 11 and runs for 18 days; it’s the biggest arts festival in L.A., with 300 theatrical productions taking the stage at upwards of 30 venues, including black boxes, proscenium theatres, bars, restaurants and at least one cemetery. There’s no curation at this fringe: If a show can pay a registration fee of $250, plus what it costs to rent a performance space, it’s in. This doesn’t necessarily mean it’s ready for a discerning audience, of course; for a per-show ticket running from $10 to $20 dollars, you can expect to see everything here, from under-rehearsed monologues to full-blown musicals.

The question, again: Why would you? The old Equity 99-seat waiver agreement isn’t scheduled by Actors’ Equity Association to end until 2016. So, given that more than 500 plays are already slated to go up this year in L.A. County, what value can there be in additional hundreds? As with most artistic questions, the answer to this one has been a long time coming.

Fringe theatre culture in America is generally regarded as the creation of Ezra Buzzington, called by many—including, with some rue, Ezra Buzzington—the Godfather of the Fringe. (If you’re Googling him, he was formerly known as Jonathan Harris.) Now better known for his work in film and television, Buzzington found himself doing plays in Seattle in the late 1980s, and recognized a scene that wasn’t doing enough to help itself.

“Lots of good little theatres were shooting themselves in the foot,” he recalls, “by scheduling openings on the same night, by not going halfsies on advertising.” Buzzington organized a collective of about 15 small Seattle production bodies with the stated intention “to facilitate communication between all fields and levels of production.”

“Out of that,” Buzzingtan recalls, “I created a festival to celebrate intimate theatre, with of course a more political agenda: to create audience, to call attention to our vibrant scene. Which it did.”

Buzzington modeled 1990’s first annual Seattle Fringe Festival after what he calls “the incredibly celebratory circuit of Canadian fringe festivals,” and also of course on the mother of fringes, the Festival Fringe in Edinburgh, Scotland. Of course, Edinburgh has an actual mainstage arts festival of which its Fringe is, well, a fringe, while other fests have embraced the term to denote work outside their city’s theatrical mainstream.

What these fringes had in common was that none curated the work; they took all comers, though, as Buzzington notes, the “fringe” label was “about making something out of exclusion, because the established scenes didn’t want what we had, which we thought was quite wonderful.” Fringe fare is not necessarily defined by its limited appeal, but it tends to be work that’s not at all certain of returning its investment—personal projects theatre artists tend to hold dear to their hearts, as opposed to the kind of broad attractions that pay the bills.

The phrase “art for art’s sake” can be a hallelujah or an obscenity, depending on who mouths it. But shows created specifically for a life in festivals have become an end in themselves. Some audiences flock to fringe festivals around the world for just such attractions. Still, Buzzington warns, “Nobody can define fringe, which makes it difficult in terms of focus, but it’s great in terms of inclusivity.”

Buzzington’s involvement with Seattle Fringe ended after three years, but the festival ran for more than a decade without him before it ultimately suspended operations in 2003. (A new Seattle Fringe ran in 2014, but did not continue this year; its management was not affiliated with the original organization.)

Knocking around in late-’90s New York, an undaunted (“or,” he muses, “unintelligent”) Buzzington accepted an invitation to collaborate with Aaron Beall, owner of the downtown venue Todo con Nada, and Present Company artistic director John Clancy, to create the New York International Fringe Festival, or FringeNYC. First mounted in 1997, FringeNYC broke with fringe tradition in that it was (and continues to be) an adjudicated festival.

Explains Buzzington: “The one thing every fringe festival in the world must serve is the god of the local demographic. New York audiences historically only like to think they’re taking chances. If you’re doing a very experimental piece downtown, you’re hard pressed to get an audience. The only reason we adjudicated in New York was because the audience is less adventurous than, for instance, L.A.’s. We did it to say to potential customers, ‘These shows are worthy of your time.’ And it worked.”

That first year, FringeNYC received hundreds of submissions for 10 venues and whittled them down to 100 acts. Buzzington also instituted a policy that has since become both remunerative and controversial: a gross-profits kickback requirement on future productions of shows originating at the festival, with proceeds to enrich FringeNYC.

“I wanted to marry the world of commercialism with radical art,” says Buzzington. “And within five years Urinetown [which played the 1999 festival] was on Broadway. So, you’re welcome, Fringe. But I moved to Hollywood before the first festival opened. My work as founder was done.”

Once in Hollywood, Buzzington continued to work in small theatre, but he wasn’t interested in founding another festival. That was left to others: Between 1999 and 2005, a local consortium of small experimental theatres, including Ghost Road, Zoo District, Actors Gang, Theatre of NOTE and Open Fist, ran a curated, fringe-esque festival called Edge of the World Theatre Festival, or EdgeFest for short, mostly in small Hollywood venues but also at downtown’s Los Angeles Theatre Center.

Over time, though, EdgeFest lost money and momentum, and it wouldn’t be until 2010 that another similar venture would get off the ground. The seeds for Hollywood Fringe Fest began when a young theatre artist named Ben Hill moved to L.A. from Iowa in 2007, looking to make his mark. “The outsider view of Los Angeles was that it’s all about film and TV,” Hill says, “so I was excited to find hundreds of theatre companies. My wife and I would walk up and down Theatre Row, smiling at each other. But audience seemed to be a problem for a lot of places.

“Having worked at the Hatchery Festival, adjacent to Washington, D.C.’s Capital Fringe, I’d seen firsthand how it enlivened the 501(c)3 crowd,” says Hill, referring to the tax-exempt status under which nonprofit arts organizations (and churches) operate. “Fringes give birth to a lot of companies, and they’re an instigator for new work. It might cost me $200,000 to fully mount a new musical, just to find out my book doesn’t work. At a fringe, for about 1,000 bucks I can get a bare-bones version on its feet and see what I’ve got.”

Hill studied models he liked and those he thought wouldn’t work; he looked at the Orlando International Fringe Theatre Festival, for one (“It’s basically a lottery, and the rest of the shows, well, you find your own venue”), and FringeNYC (“You apply, it’s a curated thing, like ‘this is the aesthetic we want to include’”), and concluded that “a lot of festivals are connected only by the word fringe.”

His favorite, uncontroversially, was Edinburgh, where he’d gone often enough that it made an impression. “A wonder of the world,” is how he describes it. “A football-stadium crowd there to celebrate performing arts! It led me to think their model of the entrepreneurial venue should become our model.”

At that point Ezra Buzzington had been acting in L.A. for years. He had been approached about starting another West Coast fringe but wasn’t interested. Then he heard that some kids—festival director Hill, producing director Dave McKeever, development director Kan Mattoo, communications director Stacy Jones Hill—were close to getting one off the ground. So Buzzington contacted Hill and they met at the Groundwork coffee shop. Recalls Buzzington, “The way they answered my questions proved they were serving the appropriate gods of art and commerce.” The Godfather had given his blessing. (He’s since had an advisory role.)

The Hollywood Fringe Festival (HFF) kicked off in 2010 with 756 performances of 180 uncurated projects. This year’s 300 entries will perform a total of 1,400 times. By contrast, FringeNYC is expecting to present a little over 200 acts this August, while last year’s Edinburgh Fringe had over 3,000, for 50,000 performances. Hill’s intention seems to be to catch up.

HFF follows “the Edinburgh model: Here’s a neighborhood, find your own venue, have fun,” says Hill. “We’re not renting out spaces, we’re not producing shows. We’re facilitating and allowing the business community to interact with artists. There’s no liability for us, so we continue to grow.”

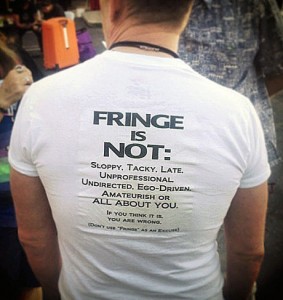

All that unregulated growth has spawned some backlash from critics, Buzzington prominent among them, who argue that there are too many unready shows among the offerings. The Godfather has composed a list of the things fringe isn’t supposed to be, including “sloppy, tacky, late, unprofessional.” He’s had a T-shirt printed up to commemorate these rules, many of which he feels were broken by some participants in last year’s HFF. “I’m a little bit of a disciplinary father,” he admits, though he’s also a little bit of an indulgent grandpa, presenting several awards at the end of each festival.

Hill deflects: “Obviously, in an open-access festival you’re going to see some shows that you don’t like. I’ve heard people say they saw their best show of the year at Fringe, and also that they saw the worst show ever. But sometimes seeing bad theatre is a lot of fun. Everyone in the audience with you will always be kindred for having sat through that thing together.”

Hill does take seriously the criticism that some shows could use practical help. In 2015, HFF has sponsored events about once a week since February to help participating artists network with landlords and vendors, and to receive the message that professionalism is a virtue, not only in stagecraft but in marketing. Hill says that 65 percent of seats sold last year, and that participants have a strong mandate to do their own ticket selling and relationship-building. “You’ve got to hustle,” says Hill.

The rationale for an entrepreneurial festival is simple: the freedom to fail without going broke.

“Your first play is going to suck, and your first draft of your 10th play isn’t going to be perfect either,” he says. “You can’t lock yourself in a room and know whether you’re going in the right direction. There are so few opportunities to see your play go up without going into credit card debt. That’s why Fringe exists: We need that chance to see it.” What’s more, he posits that “with its side-letter exemptions, Fringe will become the Equity playground, more so every year.”

He refers to the agreements that Actors’ Equity makes with festival organizers, allowing union actors to accept small stipends for limited work on non- or pre-commercial experiments. Buzzington agrees, going so far as to postulate that the fringe should become the new theatre model in America, galvanizing the next few decades as the regional theatre movement did in the mid-20th century.

Hill and Buzzington share another perspective on the importance of HFF to the larger Los Angeles theatre scene: relevance. Hill elaborates: “In Star Trek, when the Federation first makes contact and the other races have developed warp technology, that’s a sign they can take those people seriously. If you were putting together a checklist of what makes a theatre town, on that checklist is, ‘Are they doing world premieres?’ and ‘How many Equity theatres do they have?’ A really big one is, ‘Do they have a fringe festival?’ It’s a sign we’re doing our part.”

Steven Leigh Morris, playwright and dean of Los Angeles theatre critics from the current perch of LA Weekly and StageRaw, is enthusiastic if equivocal.

“It’s about perception, isn’t it?” he says. “The Fringe is getting taken more seriously by financial sources. As outreach it’s very good. People assume it’ll be standoffish and cliquish and a cultural wasteland, but what strikes them most about Fringe when they roll in is the generosity, the supportive, network-y kind of thing. We have not had it long enough to reach overseas as a force, but it’s altering a perception nationally for the better, if only in that people come and see that, ‘Hey, there’s a lot of theatre here, and a lot of it’s very good.’”

And between June 11 and 28, you can see a lot of it at the HFF, since only 10 percent of this year’s acts are from out of town. More about those artists, designers and technicians—and about how the Hollywood Fringe stacks up against other fringes they’ve played around the world—coming up in the second installment of this two-part series.

Jason Rohrer is a theatre and film critic based in Los Angeles.