ST. LOUIS, MO.: As the one-year anniversary of the shooting death of Michael Brown by police officer Darren Wilson approaches in Ferguson, theatre artists across America have been seeking ways to represent this controversial case and its volatile aftermath. But Lee Patton Chiles’s newest play Black and Blue may hit the closest to home: It’s the first full-length work on the subject to emerge from artists who live and work in the St. Louis metropolitan area.

The piece is a commission from Gitana Productions and runs through June 21 at various locales throughout the city. As the former artistic director of the now-defunct Historyonics Theatre Company, Chiles spent 15 years crafting theatrical works from historical events, using only verbatim quotes from verifiable sources to construct dramatic arc and dialogue. Adapting this technique, Chiles and Gitana artistic director Cecilia Nadal interviewed community members from a wide array of backgrounds, including local police officers, attempting to give voices to overlooked individuals in the crowd.

Recalled Chiles of the process: “The people on the ground—be they police or protesters—got drowned out.” Indeed, it was hard to keep up not only with the people involved but with the events themselves, she said. “This story was a challenge, because the story kept growing with each killing of an unarmed black man by police. Each death could be its own play.”

Interviews shaped Black and Blue as a spoken-word drama, one that attempts to bridge the ever-widening chasm between the African-American community and police forces in St. Louis, as well as throughout America.

Black and Blue is not the first work for the stage to have been inspired by these events. In November 2014, the New Black Fest in Brooklyn staged a reading of Hands Up: 6 Playwrights: 6 Testaments, a series of monologues by six emerging black male playwrights that explored “the well-being of black men in a culture of institutional profiling.” More recently, Phelim McAleer’s Ferguson stirred controversy and actor walkouts in a brief run at Los Angeles’s Odyssey Theatre, as McAleer—a conservative filmmaker and activist—staged a reenactment of the shooting based on grand jury hearings that absolved officer Wilson

Meanwhile, Repertory Theatre of St. Louis has commissioned a new solo piece about Ferguson from Dael Orlandersmith, which will appear next summer as part of its Ignite! New Play Festival.

While some social critics may suggest that there is not yet sufficient emotional or historical distance to accurately frame the context of the Ferguson narrative, Chiles insists that, with similar incidents making headlines across the country, the time to tell these stories is now.

“The story of Ferguson is still being written,” she said. “It’s still changing. The story hasn’t ended and it won’t end for decades.” Echoing her collaborator’s sentiment, Nadal exclaimed, in a curtain speech on the production’s opening night at the Missouri History Museum: “Healing should not wait a year.”

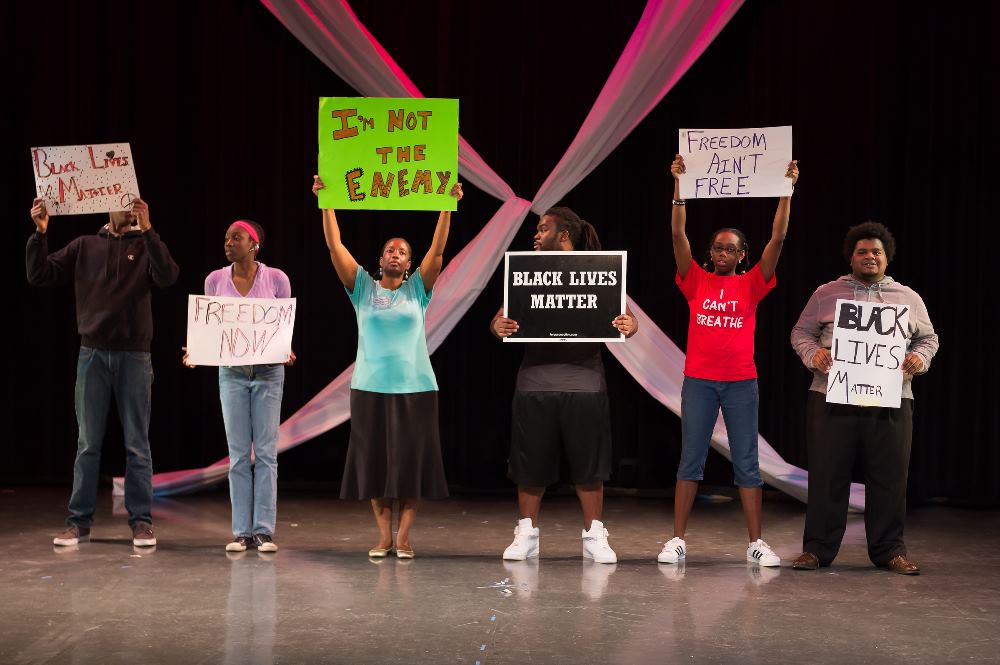

Black and Blue insists that St. Louis and the rest of America is at a vital historical crossroads. Even the simple scenic design, consisting of a large open space framed by two intersecting swaths of fabric in the background, implies that society’s fate lies at a critical juncture.

St. Louis is a sprawling metropolitan area made up of dozens of independent city governments with a long history of racial tensions and inequity among the classes, plagued by generations of “white flight” and civic institutions corrupted by greed and outmoded traditions. Even after 150 years, the shadow of the Dred Scott case—which was argued in the picturesque courthouse in downtown St. Louis—looms large over the history of the region with its legacy of discrimination. Indeed, while an investigation by the Department of Justice largely corroborated officer Wilson’s version of events in the Brown case, it also painted a disturbing picture of systemic, institutionalized racism in the St. Louis police force, including—as characters in Black and Blue repeatedly mention—the practice of using law enforcement in the region’s poor black neighborhood as a means of generating revenue.

As Chiles put it, “From slavery to Jim Crow to the Civil Rights Act to white flight to photo IDs being required to vote, to all the systems that society and the government have put in place to trap blacks in a self-perpetuating poverty, white America has never really comprehended how much we are still dominated by the legacy of slavery. We carry in our minds and hearts slavery’s legacy—that black Americans are not equal. We need to unlearn that mindset if we are to move forward as a nation.”

Black and Blue is not pure documentary theatre, as it features significant original content alongside material derived from interviews and social media (Chiles estimated that 75 percent of the dialogue comes from these transcripts), as well as moments of dramatic experimentation. Multiple voices are compressed into composite characters who recur through the action in an attempt to thread the experiences of a community into a loose story arc.

One of the most compelling aspects of the performance is the intentional mixture of seasoned professional actors and community members in the cast. In a clear attempt to ensure honest representation onstage, the latter voices are essential in destabilizing the conventional divide between audience and actor. Moments of direct address openly challenge the audience to discard the role of passive observers—not only of the theatrical event itself but also of the events unfolding outside the auditorium walls.

Two particularly poignant moments feature actors invoking the interviewed voices of mothers from affluent St. Louis neighborhoods, lamenting the dangerous world their sons have inherited. One, an African-American law professor, outlines the cumbersome to-do list she must complete to ensure her sons’ safety when she travels. To prepare for her absence, she feels compelled to reintroduce the young men to the local police and her neighbors in order to stave off suspicion and fear simply due the color of their skin. The other, a white mother of a biracial son, prays that her son may remain lighter-skinned as he matures, in order to protect him from harassment and deadly cases of racial profiling.

The staging of Black and Blue also presents many instances of pure visceral impact difficult to capture adequately in writing. The dramatic action is frequently interrupted by protest chants led by intensely charismatic actor/singer/songwriter DYCE. In those moments, the cast snaps into life with furious focus, bedecked in hoodies and carrying familiar signs. These interludes clearly document the interrelationship between protest chant, work song, spoken-word poetry jams, step dancing and hip-hop. In truth, the performance could use more moments like these, which channel the righteous anger that erupted throughout the city during the fall of 2014.

When a group of out-of-touch white citizens is questioned by a notable local black news anchor in order to gain “perspective” on the events unfolding in Ferguson, the scene takes on aspects of the subversively ridiculous, as African-American cast members don grotesque white Lycra masks with crudely drawn faces on them, transforming them into human mannequins. One citizen even repeatedly asks the reporter, “Can I touch your hair?”

Conspicuously absent from Black and Blue are some of the more recognizable—and controversial—elements of the Ferguson narrative, such as the iconic “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot” slogan, which Chiles intentionally excised, due to recent eyewitness and forensic evidence that disputes reports of Brown’s posture prior to the shooting. If nothing else, the phrase and gesture are irrevocably linked to the protests as a potent metaphor for the public distrust of police by the local African-American community.

Time will tell what will emerge as the legacy of Ferguson, Baltimore and a host of other cities. For now, this first generation of stage work serve as a reminder of the raw, firsthand artistic impressions of the contemporary moment, and of the need to cry out for healing while the wounds are still fresh.

Robert L. Neblett is a professional director, dramaturg, educator, and arts writer currently located in the Tower Grove/South Grand neighborhood of St. Louis, a rallying point for many of the city’s community organizers and activist voices.