What a temptation! Chef Pierre has just invited you on a delectable “cook’s tour of the globe”—at no extra charge over your theatre ticket. This smooth-talking celebrity cuisinier, standing before you on a gleaming white stage floor, sounding professional and knowledgeable, is making an offer you can’t refuse.

But before you accept his enticing invitation, look in your program and see who’s behind it. This will be no culinary experience; au contraire. In fact, you’re about to embark on a dangerous journey of transformative political theatre.

Belarus Free Theatre has returned to New York for the third time in five years with another urgent production, and its newest creation, Trash Cuisine, is playing to sold-out houses at La MaMa ETC in Manhattan’s East Village through May 17. Like all previous BFT productions, it calls our attention to a fundamental injustice by use of a metaphor: In this case, the target is capital punishment, and the unlikely metaphor is international cuisine.

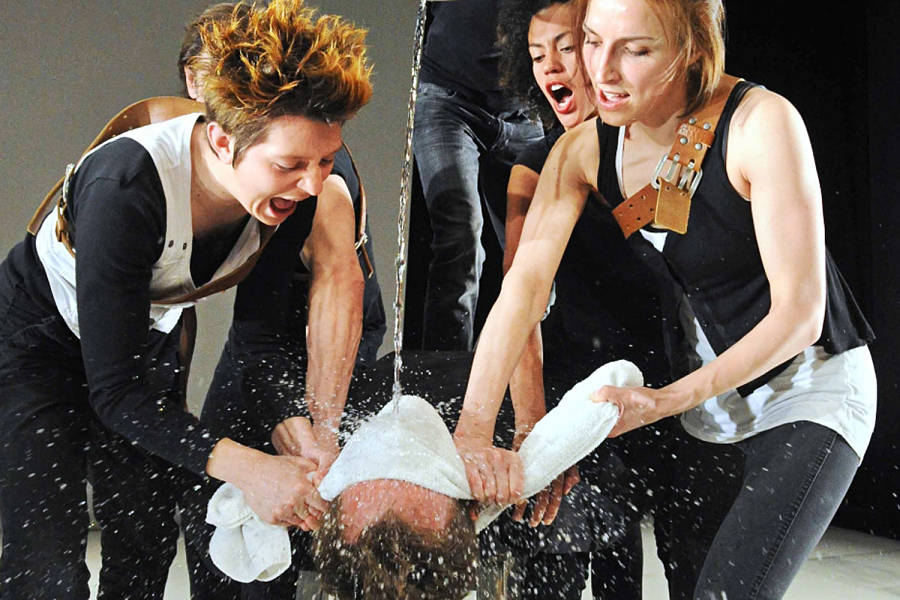

While Chef Pierre cooks onstage, BFT’s 8-member troupe enacts a dozen executions of every kind from around the globe in recent history: gas chamber, beheading, firing squad, stoning, waterboarding, lethal injection and electrocution. The devised text is compiled from verbatim accounts, interspersed with excerpts from Shakespeare’s plays. And while the 12 scenes are isolated examples of capital punishment around the world, they nonetheless coalesce into a compelling and coherent narrative.

It may sound horrific, but thanks to BFT’s nonrealist artistic methodology, it’s utterly mesmerizing. Using the Brechtian technique of verfremdungseffekt (or “distancing”), BFT underscores 90 minutes of searing theatre images with soothing contemporary music (a lone guitarist sits to the side, playing original jazz to electronic accompaniment). On a stark white floor before an upstage white wall, the actors, clad in black and white, symbolically and ritualistically perform these terrible acts with nothing but a stack of wooden barstools, some rope and other symbolic props. Meanwhile, on the sidelines, Chef Pierre displays his culinary talents on a portable cooktop.

The first scene sets the tone. “For starters: strawberries and cream!” enthuses Pierre. Two young women sit across from each other at a makeshift table, eying a huge bowl of bright red fruit, topped with sweet white foam you can almost taste. As they dip their fingers and lick them in frothy delight, they casually discuss executions, while downstage, a group of black-clad executioners strip two victims naked and lay them out on a black plastic sheet. As the girls sip their champagne, the executioners wrap the corpses and drag the body bags offstage; a dollop of whipped cream on the forehead of each girl signifies a mortal gunshot wound to the respective victims.

That shocking juxtaposition would be enough to bring the message home. But it’s followed by 11 more scenes, each strikingly different, each accompanied by music and food. In one, Chef Pierre demonstrates how to kill and cook a tiny bird. He drowns it in Armagnac (thankfully, we don’t see this), sautés it onstage, then sits on a stool, covers his head with a large white napkin (“to hide from the eyes of God.” he explains) and proceeds to consume it. The deafening amplified sound of crunching is heard as Pierre explains how to sever the bird’s head with his teeth: “Eat everything. You may leave the head. When you are finished, sit back and contemplate the wonder of your life.” With the shocking imagery of political beheadings regularly flooding the media, the notion of man as a casual daily decapitator is almost too much to bear.

One by one these disquieting images flash before us; the music and accompanying sound effects crescendo to a deafening roar. The unrelieved shrieking of an electrocution victim has most audience members covering their ears (but not their eyes). Meanwhile, Pierre keeps cooking. Toward the end of the piece, we hear an account of the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, while Pierre frantically cooks up fragments of chopped bodies (metaphorically). It’s a grotesque image straight out of Jacobean theatre.

One by one these disquieting images flash before us; the music and accompanying sound effects crescendo to a deafening roar. The unrelieved shrieking of an electrocution victim has most audience members covering their ears (but not their eyes). Meanwhile, Pierre keeps cooking. Toward the end of the piece, we hear an account of the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, while Pierre frantically cooks up fragments of chopped bodies (metaphorically). It’s a grotesque image straight out of Jacobean theatre.

In the final tableau, two actors playing corpses hang on the upstage wall, covered in white powder, while downstage the company members, under Pierre’s direction, chop onions with large machetes. Slices fly everywhere, littering the stage, and the sharp, eye-watering aroma pierces our senses.

Behind this powerful production lies an equally powerful story: the perseverance of what may be the most courageous theatre company in the world today. Cofounded in 2005 by Natalia Kaliada and her husband Nikolai Khalezin under the last remaining dictatorship in Europe, they felt the immediate and full force of President Lukashenko’s crackdown on free expression and political opposition. The company was instantly denied official registration, facilities and permission to perform.

Forced underground, the company—eventually helmed by a triumvirate, including director/dramaturg Vladimir Shcherban—rehearsed in secret and performed in basements, private apartments, cafes and forests. Audience members were contacted by text messages to inform them where performances would be held. Meanwhile, the government initiated a campaign of intimidation and repression against both the company and audience members—actors were routinely harassed by the Belarussian KGB and banned from state-run theatres; some lost their jobs.

Somehow, during their first five years, BFT managed to get permission to leave the country occasionally and go on tour in Europe and the United Kingdom. After their initial appearance in the U.S. (in January 2011 in New York, at Under The Radar Festival), en route home through London, Kaliada and Khalezin received word from friends and family in Minsk warning them they would be arrested if they returned. So the cofounders found themselves homeless. “We left with no luggage, thinking we’d return in a few weeks,” Kaliada told the press. “But when you understand you might lose your life, you realize objects don’t really matter.” Fortunately, they had their two children with them.

Soon the cofounders were offered a home base at the Young Vic Theatre in London, where they have been given office staff support to help them regroup and function. An invitation from Falmouth University in Cornwall followed, offering them rehearsal and performance space. From this base of operation, Kaliada and Khalezin now manage a core BFT company in the UK (three artists, six support and production staff). Since 2011, they have continued to travel around the world, performing on five continents; conducting workshops at theatre schools in California, New York, Washington, London and Amsterdam; and recruiting actors along the way.

Trash Cuisine in New York features five Belarussians (two who have managed to get out of Belarus to join the company), plus three actors recruited from BFT workshops in America, Australia and the UK. As Peter Brook did in the previous generation, they’re creating a truly international, multilingual company of artists.

At the same time, remarkably, they’ve maintained a company in their hometown of Minsk, though it’s still under the boot of Lukashenko’s dictatorship. How do they function? “We rehearse on Skype,” Kaliada explains. “This is how we teach our students in faraway countries, too. We just open the computer and do whatever we need to do.”

Though the BFT company in Belarus is still underground, its ranks have grown now to 32 actors, who continue to perform in secret. “They are the most dedicated, courageous and passionate actors I know,” says Kaliada of these risk-takers. “It’s vitally important for us to continue to perform for a Belarus audience.”

As for their body of work, BFT’s first production was of Sarah Kane’s 4:48 Psychosis in 2005 in Minsk. Because of its content (suicide, bipolar disorder, sexual assault, political violence, etc.), it received instant condemnation from the Lukashenko regime, which stated, according to Kaliada, that these elements do not exist in Belarus.

“So we decided to devise our own texts,” Kaliada says. “We made a list of the 16 taboo topics in Belarus, such as religion, World War II, political kidnappings, murders, death squads and so on. And we decided that every new show we made would constitute an ‘artistic explosion’ about these taboos.”

Khalezin adds: “All our plays are based on documentary material. Finding truth is the course to creating dramatic literature. You then have to convert these truths into emotions.”

Highlights among the 19 original BFT productions devised since the troupe’s inception include Being Harold Pinter (2007), about the connection between power and violence (both domestic and political). This gripping theatre piece consists of excerpts from Pinter’s Nobel Prize acceptance speech, his numerous plays, and verbatim statements of Belarus political prisoners. Stunning images from this production include a group of “characters” trapped under a transparent plastic sheet, gasping for air, a metaphor for artistic censorship.

Discover Love (2008) incorporates stories from women in Belarus, Asia and South America whose families have disappeared or been kidnapped, imprisoned or murdered for political reasons. Minsk 2011: A Reply to Kathy Acker offers a collage of images from the Belarus capital, depicting a culture of sexual depravity, violence, alcoholism, disease, brutality and corruption. As damning it is about life in that city, the latter production ends with a poignant direct audience address from cast members sitting on a row of red chairs before a red carpet (representing blood and pain), speaking of a homeland they love no matter how much it has abused them.

The above-mentioned productions have all been performed as part of the Under the Radar Festivals of 2011 and 2013 (at the Public and La MaMa), and, like Trash Cuisine, all are presented on a bare stage, typically in stark black and white, with no set elements and minimal props.

The tireless Belarus Free Theatre, in short, is more than a theatrical marvel. It is, arguably, a theatre of firsts: the first contemporary company to survive, function and flourish both in exile and at home, despite repression; the first to rely on the Internet to direct and create its art; the first to campaign globally for human rights as well as basic artistic freedom; the first to perform before the U.K.’s Parliament. The growing ranks of fellow theatre artists expressing solidarity is unstinting and unprecedented—it includes the late Harold Pinter and Vaclav Havel, Tom Stoppard, Steven Spielberg, Mick Jagger, Jeremy Irons, Emma Thompson, Ian McKellen, Kevin Kline and Samuel West.

When asked if she considers BFT to be producing “political theatre,” Kaliada replies simply: “In Belarus, because so many topics were prohibited, to express them became ‘political.’ In essence, everything becomes ‘political.’ Every dictatorship, no matter what era or what place, has the same face. Because we are artists, because we have a direct communication with our audiences around the world, we need to get them from being bystanders to active participants.”

Ultimately, necessity has become the mother of invention for the Belarus Free Theatre, now a truly global theatre company. “We are not the only ones in trouble,” observes Kaliada, speaking of her homeland. “It’s important for us to be enriched also by others’ stories—by their ideas and their struggles. The moment we think that one particular country deserves more attention than another—that’s the end of the globe.”

Carol Rocamora teaches theatre at New York University and is an esteemed translator and biographer of Chekhov.