With nationally recognized restaurants, a shopping strip that rivals Fifth Avenue and its own Millennium Park—a crowd-pleasing space complete with a bandshell by starchitect Frank Gehry—Chicago is light years from the metropolis depicted in Theodore’s Dreiser’s girl-gone-bad Sister Carrie, or Upton Sinclair’s stomach-churning meat-packing exposé The Jungle. But when the city’s Court Theatre presented an adaptation of Richard Wright’s Native Son last year, that harrowing, Chicago-set tale of a black youth’s wrong turn (penned in 1940) seemed all too contemporary.

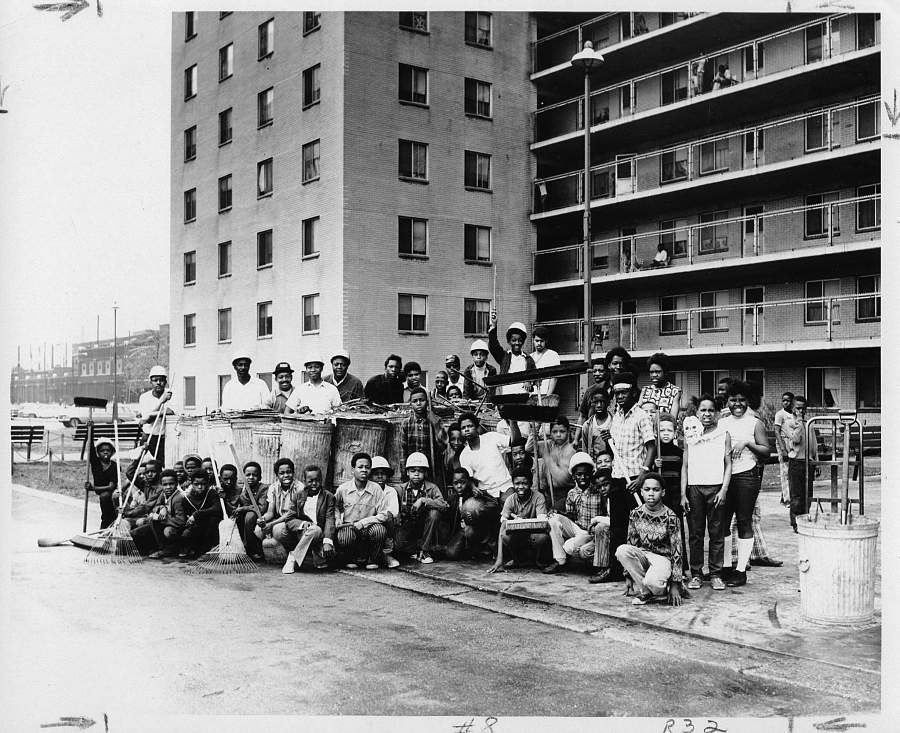

No wonder. Chicago remains one of the nation’s more segregated cities, and race informs the culture here as it has for decades. One of the most potent manifestations of that persistent wrinkle in the city fabric is its public housing. The earliest buildings went up in the 1930s, row houses erected for white families. But as early as 1940, segregationist policies pushed the bulk of construction to poor black neighborhoods, mainly on the city’s South Side, where high-rise towers became the norm. The Robert Taylor Homes alone, located in a four-mile stretch of public housing on State Street, comprised 28 buildings housing over 27,000 people.

Beginning in 1999, the Chicago Housing Authority (CHA), which once managed tens of thousands of units, began to downsize. The goal was not only to reduce the scale of these communities by demolishing the decaying, high-rise developments, but to deploy a mix of subsidized, affordable and market-rate housing—the idea was to create more organically viable neighborhoods and combat the social ills that so often plague public housing. For the past six years, PJ Paparelli, playwright and artistic director of American Theater Company, has worked to unravel the skein of that system, one in which race and poverty are so tightly entwined.

That effort took final form in The Project(s), a documentary drama running through Apr. 24–May 24 at ATC.

“My first trip into the heart of the South Side was for this project, and I was embarrassed by that, to be honest,” Paparelli confesses. “I wondered whether I should do this. I am not from here, and I have no experience of public housing. But I realized that if I’m going to both diversify this company and help to add pieces that are more diverse to the range of new plays being developed in Chicago, then that’s all the more the reason I need to take this on.”

A son of Scranton, Pa., Paparelli earned his BFA in directing from Carnegie Mellon University, and before settling in Chicago, he served as associate director of D.C.’s Shakespeare Theatre Company, then as artistic director of Perseverance Theatre in Juneau, Alaska. At ATC, he directed an attention-getting revival of the Chicago-born musical Grease and presented Kimberly Senior’s debut production of Ayad Akhtar’s Disgraced. Last season, he helmed the debut of Stephen Karam’s The Humans (scheduled to play in New York at the Roundabout Theatre Company this fall, with Tony winner Joe Mantello directing).

One of Paparelli’s most notable endeavors is columbinus, his documentary-style play (written with Karam) that examined adolescence in the aftermath of the 1999 Columbine High School shootings in Littleton, Colo. The piece, which has been mounted across the country, was generated from extensive interviews with students, parents, police and school officials. Paparelli and his current collaborator, Joshua Jaeger, employed the same interrogatory approach to create The Project(s), taking to the field to meet with residents, urbanists, architects and historians.

“We have probably over 3,000 pages of transcripts from over 100 interviews,” Paparelli notes. “What was challenging was making sure we had a balance of voices. We didn’t go in thinking, ‘This is the story we’re going to tell.’ That had to emerge out of these interviews. You really have to trust the process.”

Aiding Paparelli in that process was social scientist and historian D. Bradford Hunt, author of Blueprint for Disaster: The Unraveling of Chicago Public Housing, who explains the background situation this way: “Public housing advocates during the New Deal and beyond subscribed to the idea that bad housing was at the root of social ills. Replace the bad housing with good housing—modern bathrooms, kitchens, light—and social problems would fade away.”

But, as Hunt notes, reality fell short of that vision. “The federal government paid to build the projects, then expected local housing agencies to maintain them, using income from tenant rents. But public housing also wanted to serve the poor, who could not afford much rent. As a result of this tension, funds for maintenance were never sufficient.”

Hunt introduced Paparelli to folks who knew firsthand the truth of life in the projects, such as photographer and community leader Annie Stubenfield, who grew up and raised her children in public housing and now lives in one of the newer, mixed-income developments. “The CHA let everything go,” Stubenfield says. “The buildings weren’t conducive to living, and when the rents went up, anyone who was making money left. That’s when the CHA started renting to just anyone.”

Despite the degradation of the properties and the arrival of drug dealers and gangbangers into what had been communities of working poor and working-class families, social disintegration was not universal in city-run projects. “We went to school, we got married, we travelled,” stresses Stubenfield. “There are a lot of good stories.”

While the philosophical and structural complexities of public housing can only be fully understood through the kind of deep research that would never “play” onstage, the assembled voices of The Project(s) bring the issue home in a way that resonates with more impact than would any academic analysis. “A lot of people think that the projects were great for poor black folks,” former resident Carl Bryant told Paparelli, “but I think the projects created a culture that destroyed black men.”

As the CHA’s program of demolition and incremental new construction continues, there are still not enough homes for the families that need them. Former resident Sam Alexander observes, “When you dismantle these buildings, you dismantle families.”

“How do you tell a complicated story like this?” Hunt asks rhetorically. “The policy stuff alone can be mind-numbing. And how do you communicate the range of emotions that residents and others experience? Public housing was home, but also, for many, a source of profound stress. It was a space of housing security—low rent—and a space of housing insecurity—violence. That’s an incredibly complicated story for a 100,000-word book, but in a play, how do you capture that?”

Wrestling myriad experiences and viewpoints into a compelling, informative and incisive theatrical experience took time. “Once you get a draft of the play,” relates Paparelli, “then you’ve got to figure out an aesthetic and not just present a series of talking heads. That needed to come out of the culture—a means of storytelling that connected to who these people are.”

Impressed by the sounds that echoed in the hard, open spaces between the high-rises—music, conversations, children playing—Paparelli found an expressive answer in stepping, the urban dance form in which the whole body acts as a percussive instrument and the performers’ voices accent the movement. He called on Jakari Sherman, artistic director of D.C.’s Step Afrika!, to devise the dynamic tissue that binds the multiple voices and enlivens the stage picture. “Following the first Great Migration, and even more so after the second migration, African Americans were attending college in larger numbers,” according to Sherman. “They formed fraternities and sororities on these campuses, and it was through these organizations, in the ’50s and ’60s, that stepping began to emerge.”

With eight actors delivering the words of Paparelli’s multiple sources, The Project(s) begins with the early promise of public housing and details its downward spiral. “Public housing’s demise has left deep scars on many cities, and mayors and housing officials are desperate to not repeat the past,” states Hunt. “We’ve swung the pendulum too far to the side of extreme caution in rebuilding public housing, with the result that we’re moving far too slowly to rebuild communities that have been torn down.”

While it would be easy to construe the piece as an act of agitprop, Paparelli insists his intentions are not so doctrinaire. “The play doesn’t say, ‘This is what we need to do,’ because we don’t know. But it asks, ‘What is our country’s obligation to the poor?’ It’s about empathy. It’s about dialogue. We have to talk about this, and not from the same platforms that we’ve always talked about it.”

Thomas Connors writes about theatre in Chicago.