Every month, American Theatre goes behind-the-scenes on the design process of one particular production, getting into the heads of the creative team. This month’s contender: Airline Highway by Lisa D’Amour from Steppenwolf Theatre Company, currently being present at Manhattan Theatre Club.

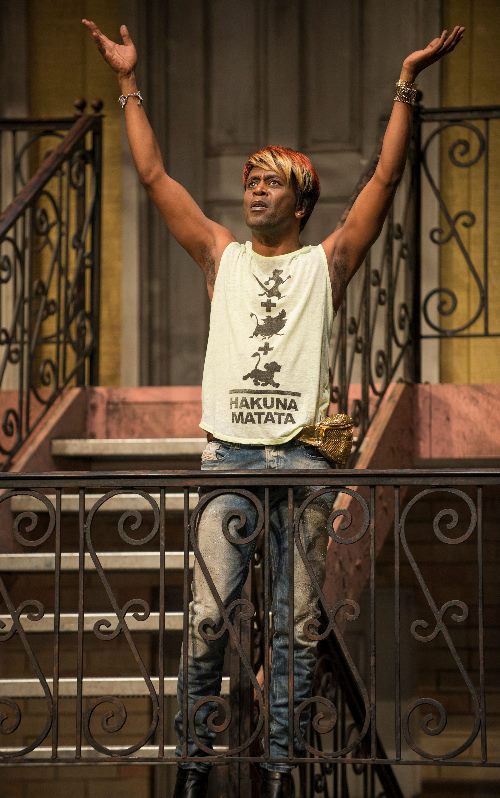

An old motel may be an atypical place to hold a pre-funeral, but for the still-living Miss Ruby and the colorful New Orleans denizens who love her, the Hummingbird is a testament to a resilient community. In the Steppenwolf’s world premiere of Airline Highway, which began its Broadway run April 1, the production crew used the real-life NOLA as inspiration, giving a motel they spotted on the actual Airline Highway a second life onstage.

Scott Pask, SCENIC DESIGN: Airline Highway is a glimpse into the social center of a community that exists on the fringes of the vibrant city of New Orleans, where many are part of the legions of workers in the less lustrous facets of the service industry. The Hummingbird Motel is their home and gathering place that has lost all traces of its former glory and stands as a faded remnant, run-down, and having weathered the ravages of time, neglect and Hurricane Katrina. Its tarnished patina is a shared quality among its inhabitants who gather and live there. The goal of the design process was to create a dynamic playing space that solves the many spatial challenges of the play, while emanating a palpable authenticity. Many details reference a [real-life] motel, the London Lodge, on the road into the city that is the play’s namesake.

The parking lot [of the Hummingbird], with its two-storied architecture as background, creates an amphitheatre-like space for the events that take place over the course of a day in the life of this place—before, during and after a “living celebration” for its most lustrous inhabitant, Miss Ruby, the virtual mother to them all. The motel comes to vibrant life as it is decorated for the festivities, transforming into an alluring space, a sparkling rhinestone, flaws and all. And by the end of the play, when all is seen in the illuminating daybreak, it is returned to its aged, dilapidated self.

Japhy Weideman, LIGHTING DESIGN: The primary intention of the design is to simply put the Hummingbird Motel onstage in full scale and build an environment around it that feels fully authentic. While there are moments that become more heightened and theatricalized in Act 2 of the play—with the celebration of Miss Ruby and her speech—the rest of it is trying to keep a hyperrealistic shape to the quality of light. The show starts at dawn, around 6 a.m. The motel is mostly dark with a few exterior sconces and the Hummingbird Sign key-lighting the scene. Slowly, the sky begins to shift, becoming lighter, and low, warm side light begins to graze across the pavement as the play unfolds. We use a light grey-blue painted drop to create the surrounding sky; this serves to tie the time of day together with the light onstage. There’s a lot of practicals on the set: wall sconces, an industrial street light, neon sign, interior lamps behind the curtains in each room, and other sources. For the night scenes I began with those and then started to sculpt light around them that feels like it’s being emitted from those sources.

The challenge was to create a realistic environment while also having enough light on the stage to support the text being delivered. We have to light the actor and still try to find a way to make it feel as naturalistic as possible. If you get too much light, and from the wrong angle, it starts to look like a piece of theatre.

I had the opportunity to go to New Orleans and visit the London Lodge. I went around 9 p.m. and walked around the area and photographed, noting the different qualities of light from the various sources, and the darkness that surrounds the place. I admit, I felt a sense of uneasiness. Not that it was dangerous, but I didn’t feel safe.

Airline Highway by Lisa D’Amour ran at Steppenwolf Theatre Company in Chicago Dec. 4, 2014–Feb. 14, 2015. It will open at Manhattan Theatre Club on April 1. Both productions are under the direction of Joe Mantello and feature scenic design by Scott Pask, costume design by David Zinn, lighting design by Japhy Weideman and sound design and original music by Fitz Patton. In addition, the Steppenwolf production featured fight choreography by Matt Hawkins, dialect coaching by Eva Breneman, stage management by Malcolm Ewen and assistant stage management by Christine D. Freeburg.