So with little time to spare and lots of internal debate, we decided to replace the previously announced Lend Me a Tenor with The Pope and the Witch. In New York, I was accustomed to season schedules changing all the time, so I was taken aback that the substitution of one play for another was considered amateurish and unacceptable in San Francisco, particularly in the first year of a new regime. But substitute I did, making the additional mistake of trying to explain the switch by being honest about the blackface incident in the school. At that point, the howls of reproach began in earnest. It was bad enough, I was told, to bow to the politically correct pressure of a few students and displace a farce that had run so successfully in New York. But it was sheer idiocy to replace that farce with an Italian comedy about the Pope’s vision of free abortion, in a city as Catholic as San Francisco.

Within days, I was receiving outraged letters from religious subscribers, from churchgoers and from the Catholic hierarchy itself. The city was up in arms. There were front page articles in the Chronicle and dismissive editorials everywhere (and this was in the days before this kind of crisis could get tweeted and reposted across the cyber-universe). It took me months to realize that the fault lines between the Catholic and gay communities were particularly acute during that period, and that by my actions I had placed A.C.T. directly in a toxic crossfire.

Summoned to appear at the knees of one Monsignor Ottelini of St. Cecilia’s Parish, I sat on a low stool and was castigated by an outraged priest who had just written to the chair of the National Endowment for the Arts demanding that “the NEA should seriously reconsider future grants to A.C.T. in light of their callous treatment of a significant portion of the local population.” In response to my letter of explanation, the Archbishop of San Francisco replied that it was totally unacceptable that we were “performing a play in which the Holy Father is portrayed assaulting homeless children and as supporting the drug trade.”

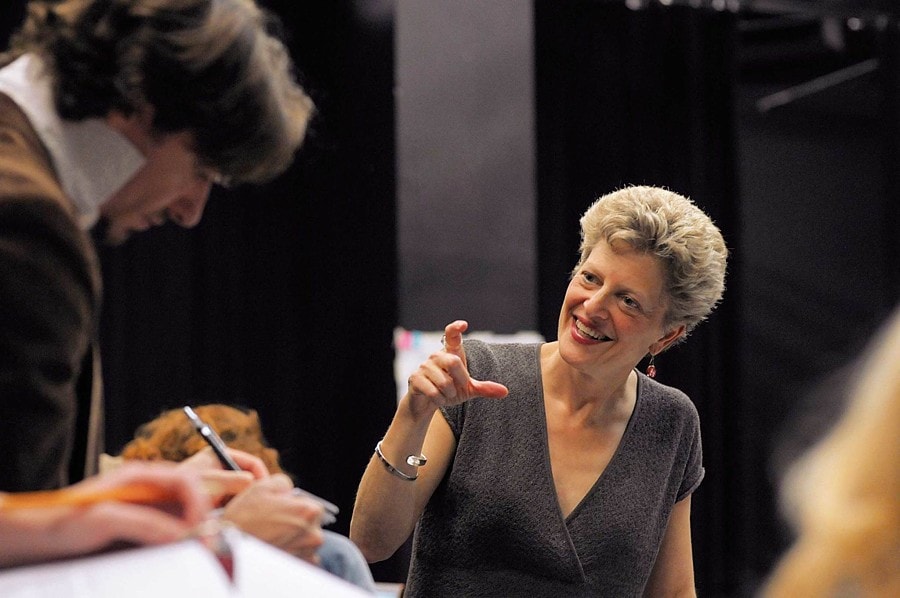

When the production finally opened, it became clear that the play itself was rather pallid in comparison to the scale of outrage it had engendered. This minor piece of Italian political provocation couldn’t stand up to the scrutiny visited upon it by press and audience alike, despite brilliant central performances by the antic Hoyle and his sidekick Sharon Lockwood. It was devastating to be met with such derision and lack of comprehension.

There were two silver linings to the debacle. One was the arrival on the scene of Alan Jones, the wise and gracious dean of Grace Cathedral, who descended from Cathedral Hill in his finest robes during the preview process and told the picketing crowds that while dissent was honorable, censorship was not. He was passionate about the right and, indeed, the duty of artists to freely articulate their worldview, and he immediately became a treasured friend and then trustee of A.C.T., eventually presiding over a beautiful blessing on the reopening of the Geary.

The second silver lining came in 1997, when out of the blue, Dario Fo was awarded the Nobel Prize in literature. I was asked to appear on “The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer” the evening the award was announced to comment on the significance of Fo’s work, and I felt a sweet moment of vindication in seeing this writer being celebrated after having been relentlessly castigated in San Francisco just a few seasons before.

But the Pope fracas was only the beginning. As I began visiting rehearsals of our next show, The Duchess of Malfi (which were being held in our scene shop owing to the enormity of George Tsypin’s set), I slowly began to discover what it was that Robert Woodruff loved so much about the play. He had been reading Camille Paglia and Susan Faludi at the time, and wanted to put onstage the graphic degradation of women that he felt was fundamental both to our own culture and to Jacobean drama. His was an eminently fair and extremely visceral reading of the text, although there was nothing particularly subtle about his conception: His brilliant set designer had created a giant metal scaffold filled with office cubicles and bisected by a huge tube through which ejaculate-colored liquid could gush on demand. For the opening tableau, female graduate acting students were enlisted to lie spread-eagled on metal desks with the skirts over their heads as their vaginas were sewn up by angry men. The incomparable Randy Danson, playing the Duchess, spent a good portion of the final acts naked and covered in blood, while a magnetic Sam Tsoutsouvas as Ferdinand tormented her. The costumes were extreme, the music was loud, the visual envelope of degraded office workers was relentless. It was a bold, graphic, shocking, rather heavy-handed reading of an admittedly violent and sexually aggressive play. And many A.C.T. subscribers, who had received no warning and were apparently used to their classics being somewhat more decorously presented, were appalled.

Their horror began at the first preview when the intermission lasted a full 48 minutes because Woodruff had decided at the last moment to put the set on wheels, and the desperate stage crew was risking hernias to try to move two tons of metal to a post-intermission position. The length of the interval gave the 600-plus-person audience nearly an hour to line up and accost me with angry accusations about how I was rapidly desecrating the theatre they knew and loved. This “in your face” approach to a classic was the last straw. The enraged crowds couldn’t wait to get home and write me hate letters about the production. I received 750 letters in all, which I collected in two large black binders that I leave in a prominent place on my office bookshelf, as a reminder, I suppose, of those bitter early days.

Woodruff had to depart the day after opening, so I was left to answer every letter myself. This was an arduous process but, surprisingly, in the long run it was also somewhat rewarding. In preparation for writing this book, I reread the entire collection of mail, and what struck me so forcefully, 20 years down the road, was the passion and intelligence expressed by A.C.T.’s audience. Despite the level of anger, it was immediately clear that these were not philistines who were arguing for pabulum or for a season of “easy listening”—they were engaged theatregoers who desperately wanted to understand what was going on at a theatre they had nurtured for years. I realized that I was no longer at the helm of a small organization in the vast cultural landscape of New York; I was running the “flagship,” and everything I did was going to be visible and scrutinized.

In responding one by one to all the charges against the casting, concept and design of Malfi, I began to forge a relationship with my audience. I tried to stay as open as possible, and perhaps because they saw my extreme vulnerability, they too became more open. But it was a lonely time. The nadir came when I discovered that a telemarketer for a local theatre was using the debacle as bait to lure our subscribers away. At the same time, Lexie got scarlet fever, and I was ready to give up.

Debacle number three came in the form of Sophocles’ Antigone, which we produced after Malfi in our smaller theatre, the Stage Door (now a nightclub called Ruby Skye). Once again, the best-laid plans had gone awry, and subscribers were angry before they even walked into the theatre. I had announced and fully intended to produce a new production of Euripides’ Hecuba to star my longtime colleague and mentor Olympia Dukakis in the title role. I commissioned the visionary playwright/translator Timberlake Wertenbaker to create a new version of Hecuba, but by the time we dove into the project, we realized it was a massive undertaking, requiring extensive music and choral work that could best be developed in a workshop. I had to take a deep breath and admit that to do it justice, the production needed time to develop. So we substituted Antigone, promising that Hecuba would emerge in a subsequent season. (Indeed, when we finally produced Hecuba in 1995, featuring an astonishing score by the now Pulitzer-winning composer David Lang and starring a ferocious Olympia, it was a triumph.)

But at the time, an already shaken audience felt betrayed. Where was Ms. Dukakis when they needed her? A.C.T. had rarely been in the business of commissioning new translations and adaptations of classics, a practice we had employed regularly at CSC, so the audience was not privy to the developmental steps it takes to ready a large-scale new version of a classical play for production. I began receiving more mail, this time with the comment that “we don’t like Greek tragedy anyway and don’t wish to see it at A.C.T.” This truly baffled me, since as far as I could tell, the theatre had almost never produced a Greek play. How did our audiences know they would hate what they had rarely seen?

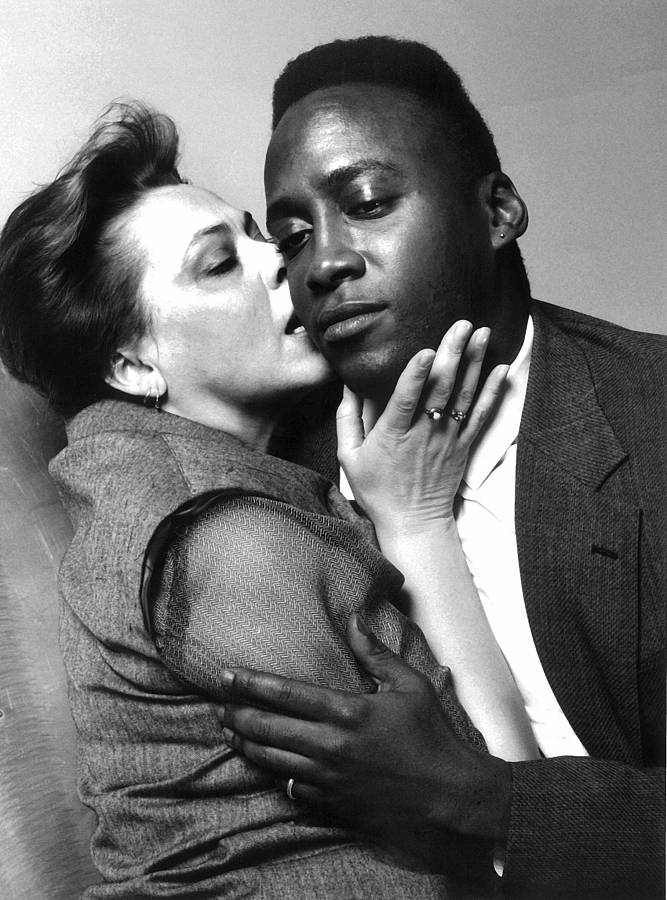

I suspected that their anxiety was tied to their expectation of boring, declamatory drama performed by people in white sheets, and I was sure that when they saw how immediate and thrilling Antigone could be, they would change their minds. As the leads in my production, I cast Elizabeth Peña, a Hispanic actress from L.A., as Antigone; Wendell Pierce, the remarkable African-American actor, as Haimon; and A.C.T. veteran Ken Ruta as Kreon. David Lang scored the play for the Rova Saxophone Quartet, who performed it live from the balcony. I set the play in the rubble of a ruined theatre, and gathered real detritus from the damaged Geary Theater to decorate the stage. We even had a row of red seats on stage that were crumpled and bent like the seats that buckled during the quake. We imagined the Chorus of old men, led by the inimitable Gerald Hiken, as aged subscribers whose primary hope was a desire to return to the status quo before the destruction.

But once again, when the production opened, a furor erupted. I had always practiced what was then called “nontraditional casting”—particularly with material as metaphorical as the Greeks—but A.C.T.’s company had been predominantly white (something Hastings had worked hard to change), and to my surprise, the audience did not seem eager to watch a multiracial cast perform Antigone. To this bewildered and bruised audience, my casting smacked of political correctness, and the letters began pouring in again. Antigone drove an even deeper wedge between the artists and the audience.