Bill Ball and the board had been warned by the San Francisco Fire Department for years that the unreinforced brick wall at the back of the stage could present a major hazard in the event of an earthquake. But in the random manner of most disasters, the culprit in the case of A.C.T.’s destruction was a loose fan housing on the roof that fell through the ceiling, bringing down the whole gilded proscenium with it. In an instant, the cables attaching the lighting grid to the ceiling moved one way and the arch itself moved another, tearing apart the surface of the proscenium like an orange peel and sending massive amounts of rubble tumbling down into the house in huge waves of destruction. It was a miracle that no one was in the theatre: Only a few hours later, hundreds of people would likely have been hurt (interestingly, the biggest destruction lay in Row G, the critics’ seats. As someone who has never been a darling of the press, this irony was not lost on me).

By the end of the 90-second temblor, there was sunshine pouring through the roof of the Geary where light had never entered before, the air was thick with plaster dust, and the extent of the destruction was impossible to gauge. The first concern of A.C.T.’s management was to make sure that no one had been hurt and that the children in the Young Conservatory were reunited with their parents. Once that was accomplished, a kind of numbness must have set in. As streams of shell-shocked people made their way across town, walking all the way downtown from Candlestick Park or trying to reach loved ones across the Bay, it became clear to the artists and management at A.C.T. that their beloved playhouse had sustained devastating damage.

Within a mere few weeks, A.C.T. was in diaspora, and would continue to be so for the next six years. It was a major turning point for the company, a moment that could easily have ended Bill Ball’s great experiment. But somehow in adversity the institution rallied: Indeed, the earthquake quickly revealed the suppleness and survival instinct that has always lain at the heart of A.C.T. Alternative performing spaces were found, schedules altered, audience members notified, and, miraculously, the 1989–90 season continued to unfold.

When I arrived at A.C.T. in November 1992 for my second or third job interview, the Geary lay in silent ruin, like a kind of modern-day Pompeii: Nothing had been touched since 5:04 p.m. on Oct. 17, 1989. The atmosphere inside was eerie and magical. The callboard backstage, covered in dust, announced the evening’s schedule and the actors’ calls, the stage manager’s coffee cup and prompt script lay in waiting offstage right, wardrobe racks and prop tables were readied.It was as if the ghosts of A.C.T. past could rise up at any moment and begin a performance.

Because of fears of asbestos, crews had stayed out of the building for months after the event. When the wreckage was finally surveyed, it was found to be extensive and structural. Ironically, the much-maligned back wall with its unreinforced brick sustained virtually no damage. But the tumbling proscenium arch tore away the fabric of the ceiling and exposed the heavily damaged roof and interior structure of the building. The photographs and video from right after the quake exposed the vulnerable bones and tissue of this stunning and delicate building, whose original architects (Bliss and Faville) had lavished such loving attention on every corner.

All of us who make theatre are forced to acknowledge with every closing night how transient our art form is; nevertheless, it was startling to realize how transient the performance space itself could be. The catastrophe had escalated the decision of my predecessor, Ed Hastings, to leave A.C.T.: He wisely felt that whoever was charged with rebuilding the building should be committed to working in it afterwards, and that was more of an extended time commitment than he was interested in making at that point in his already long and distinguished career.

Early plans for the reconstruction of the Geary had called for a wholesale reimagining of A.C.T.’s operations: The corner property—owned by the theatre but then housing a greasy spoon diner, a car rental business and, upstairs, A.C.T.’s box-office operations—was envisioned as a new, unified campus that would contain the institution’s offices, studios and school. The architect behind this original inspiration, Joseph Esherick, was a real visionary, but it quickly became clear to the theatre’s shaken board that it would be a monumental enough effort to rebuild the Geary without taking on an entire new institutional complex. In a sense this was an enormous shame, and 20 years later we are only now coming around to the realization that an institution as complex and multifaceted as A.C.T. needs a central campus. Indeed, this is the work of the next decade.

It was clear that the rebuilding of the Geary was to become the top priority of whoever was chosen to be the new artistic director of A.C.T. For me this was the most thrilling aspect of the job, and the most terrifying. I was a relative stranger to the kind of Broadway proscenium house that the Geary represented. I could never have imagined that an old-fashioned 19th-century theatre would become my treasured artistic home. The learning curve was going to be steep.

I suppose it is often true that what you don’t know saves you: If I had had any inkling of the vast challenges that lay ahead, I would never have accepted board chair Alan Stein’s job offer with such a light heart. I had to raise $30 million in less than two years without an identified donor base or even a proper capital campaign plan, and I had to do this at the same time as I was radically changing the aesthetic of the organization, attempting to rebuild the school, rethinking the entire administrative structure, stretching my wings in new and surprising ways as a director, and raising a three-year-old. I suppose it was lucky that Lexie was only three when I began at A.C.T., so that she didn’t have to read the 750 hate letters I received during the course of my first season.

The actual season began with a rare Strindberg three-hander called Creditors, which I had directed to critical acclaim the past season at Classic Stage Company in New York, in a new translation by Paul Walsh, who was to become our resident dramaturg some years later. No one told me that this taut little exercise in sexual warfare might not be the most celebratory way to begin one’s tenure at a new theatre (“A seemingly perverse choice,” sniffed critic Dennis Harvey in the San Francisco Chronicle), but at least it was a gem (and an inexpensive one at that), and I knew the script well enough to direct it while trying to solve the endless cascade of problems that were bound to present themselves during my first months at A.C.T. As soon as I went into production for Creditors, I realized that I was at a theatre without a casting director, a literary department, a dramaturg or a resident stage manager who was on my team. Navigating Strindberg’s psychological complexity while learning to steer a rudderless institution was difficult at best.

Nevertheless, Creditors opened on an incredibly hot evening in September 1993, and the press compared it favorably to the weather. The production’s Pinteresque sexual tension, precise sculptural staging and powerful cast (A.C.T. favorite Charles Lanyer, along with newcomers Joan McMurtrey and William Converse-Roberts) intrigued our subscribers, even if the play was for some more of an appetizer than a full meal. But it was a gripping evening with some vivid performances, and our audiences leaned forward and took notice.

Then the disasters began. It started with Lend Me a Tenor, the play I had selected in my rushed effort in the months prior to find a light comedy to balance the rigors of The Duchess of Malfi, Creditors and Antigone. Lend Me a Tenor’s plot revolves around an ill-fated opera production that attempts to replace an ailing tenor with another singer disguised in blackface. Already on my first day on the job, I had started to hear rumbles from the conservatory about a recent MFA acting class that had gone disastrously wrong. It was called “Rock Stars” and its purpose was to train actors to work from the “outside in,” by imitating in as precise a manner as possible the physical and vocal behavior of a chosen rock star. A misguided white student, having decided to portray Grace Jones, appeared before her classmates in blackface. This caused enormous upset in the school.

Certainly, there were few artists of color in positions of authority at A.C.T. at that time, and few safe avenues for the students to express discontent. Thus, in the wake of the Grace Jones episode, when the naïve new artistic director announced for her first season that she was programming a play that indirectly involved blackface, the place erupted. Benny Sato Ambush, an African-American director who was the associate artistic director at the time, did his best to explain to me that in the context of the school, carrying on with Tenor might be a very bad idea indeed.

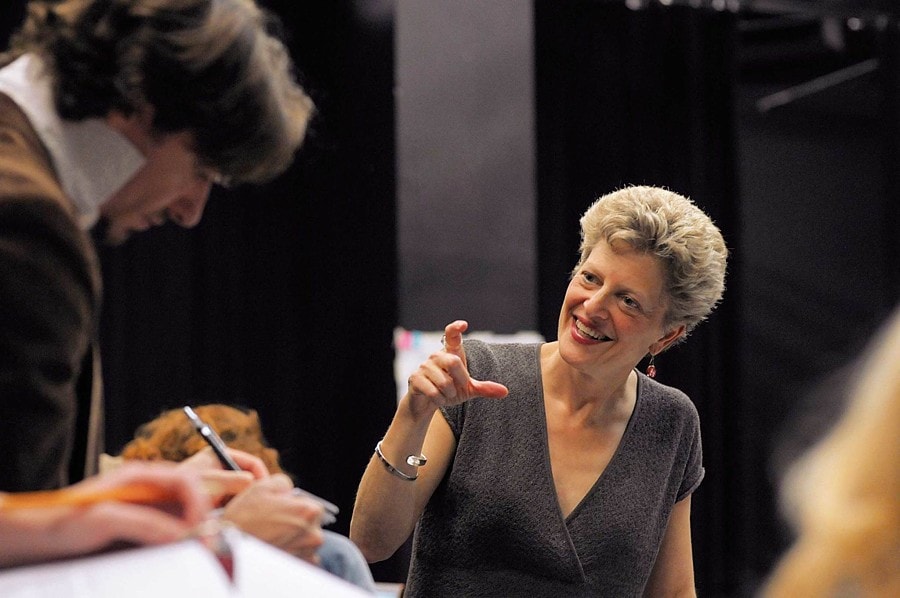

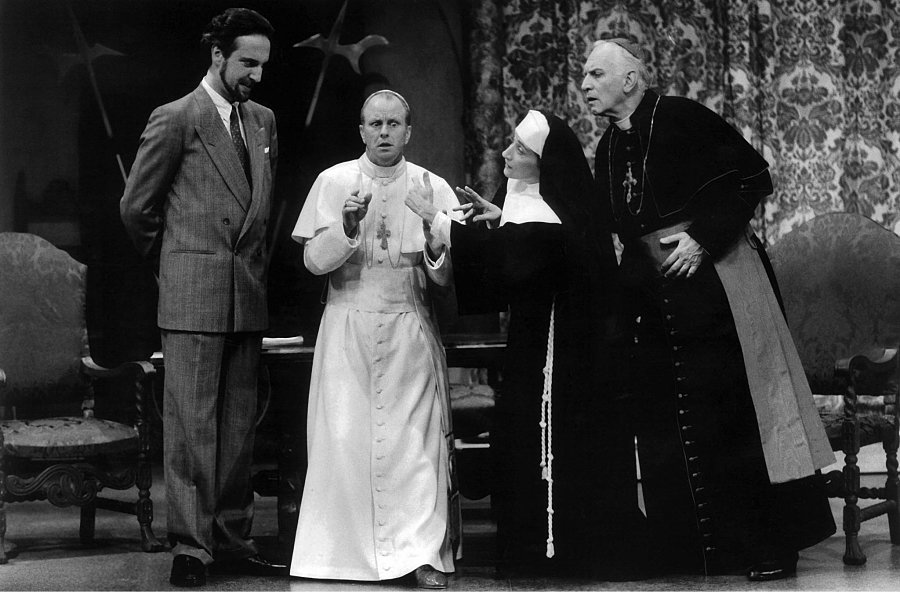

To be honest, I was not sorry to replace the slim Ken Ludwig farce with another, more interesting play. But I had no idea how myopic I was being when I chose instead a Dario Fo farce entitled The Pope and the Witch. Again, the choice happened for seemingly sensible reasons. In addition to Benny Ambush, I had made the decision to bring on board at A.C.T. a second associate artistic director, Richard Seyd, cofounder of the Eureka Theatre, a beloved acting teacher and a font of knowledge about Bay Area alternative theatre. Richard was a total outsider to A.C.T. Among his many local friends and colleagues was Joan Holden, writer for the San Francisco Mime Troupe, who had shared with him an untranslated new Dario Fo play that followed the upheavals caused when an eager Pope, in thrall to a drug-trafficking Witch, woke up one morning suddenly believing in the right of women to obtain free abortions on demand.

Seyd and Holden were excited by the energy and invention of the piece and thought the role of the Pope would be a perfect fit for Geoff Hoyle, clown extraordinaire. Geoff was another Bay Area artist who had never been part of the A.C.T. circle; the Fo play offered a lively opportunity to introduce him to our audiences, and his audience to ours. I knew how beloved Fo’s work had been amongst Mime Troupe fans across the Bay Area, and was interested in encouraging that audience to begin coming to A.C.T.