Part 1 of this essay, recounting how the author became the leader of San Francisco’s flagship American Conservatory Theater in 1992, appeared in AT’s January ’13 issue.

My generation of american artistic directors sits somewhere between the visionary founders of the regional theatre movement and the often anti-institutional independent artists who have found homes either in the commercial or experimental theatre worlds in recent years. I felt part of a group that was committed to acting ensembles, classical repertoire, large-scale new work whose goal was not Broadway, subscription audiences with a love of variety, and federal funding for the arts. We were not yet disillusioned enough to despair of institutions per se or to hold the nonprofit movement accountable for a lack of access and adventure in the field, a charge one hears repeatedly (and often fairly) today.

The founding notion of the National Endowment for the Arts was that the future of our democracy was interlaced with the future of our art forms, and that to nurture the arts there had to be subsidy that protected risk and kept artists’ visions focused on the long-term growth of the art form rather than the short-term profitability of a given piece of work. A.C.T. founder Bill Ball understood that resident theatres were given nonprofit status because they were held in the community trust (as Zelda Fichandler had so beautifully put it, “Once we made the choice to produce plays not to recoup an investment but to recoup some corner of the universe for our understanding and enlargement, we entered the same world as the university, the museum and the church, and became, like them, an instrument of civilization”). At the beginning, he took that charge very seriously.

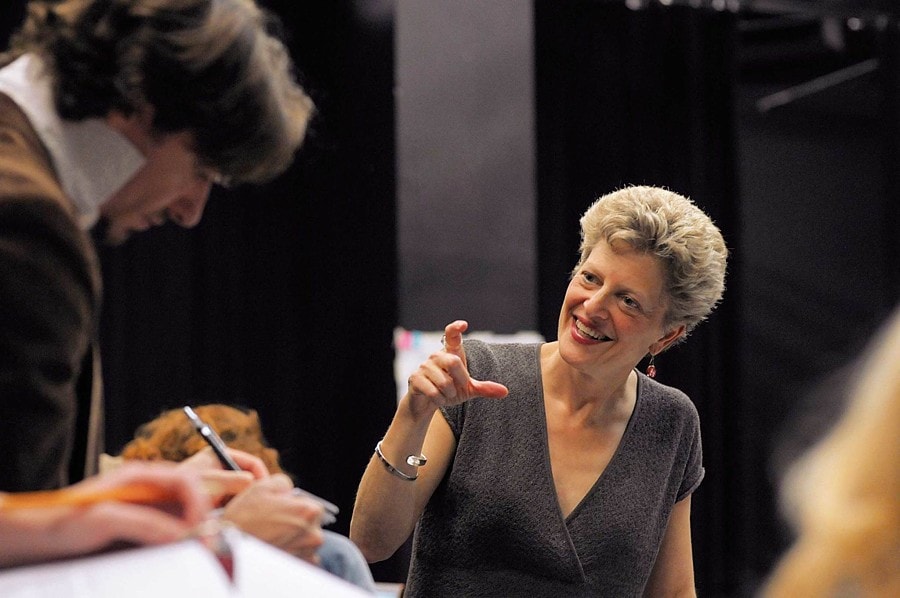

I will never be entirely sure why the board of A.C.T. decided to risk everything on me when they hired me as artistic director in the early 1990s, but I suspect it was that on a deep level, I shared some DNA with Bill Ball, whose founding “definition” of A.C.T. was as follows: “The American Conservatory Theater combines the concept of resident repertory theatre with the classic concept of continuous training, study and practice as an integral and inseparable part of the performer’s life. Our goal is to awaken in the theatre artist his maximum versatility and expressiveness.”

Ball’s company of 40-plus actors was engaged in constant artistic growth, taking and teaching classes while performing up to 17 plays in the inaugural season! Modeled on the Comédie-Française, A.C.T. was built around a large rotating repertoire, a permanent acting company and a conservatory in which actors studied and students acted. The conservatory quickly became a major training program in which young actors apprenticed at the feet of master actors while performing alongside them onstage.

The idea of a theatre that not only sustained a permanent acting company but a multi-year acting program was thrilling to me. This was how the ancient art of theatre had always been carried forward. Educated actors and an educated audience meant the opportunity to do challenging work in a sophisticated way. San Francisco’s proud separation from the entertainment industry in Los Angeles freed A.C.T. from the oft-bemoaned requirement of hiring television and film stars to populate its stage: Bay Area audiences pride themselves in knowing good theatre acting when they see it, and Bill Ball had trained his audience to recognize talent. So although I was leaving the vast talent pool that was New York, there seemed to be the potential in San Francisco for a sustained and serious theatrical exploration.

One of my early discoveries when I took the job at A.C.T. was that San Francisco was the least corporate place I had ever been, and that the good “business practices” originally envisioned by the NEA for the arts, which involved organization charts for theatres and museums that looked as similar as possible to those of banks and corporations, seemed less applicable in Northern California. A.C.T.’s precarious history as a one-man band with very little in the way of corporate structure or governance was also its saving grace. It had never become an institution in search of a mission; it was, rather, a mission in desperate search of a sustaining financial structure.

In many ways, 20 years later, I feel as if we are still searching for that elusive formula whereby a theatre housed in a 1,000-seat venue can produce serious and exciting work, while at the same time developing new plays and sustaining a highly regarded training program in the most expensive real estate market in the world. I discovered early on that survival is never something one can or should count on; every play, every season, every young actor in training, has to be its own event, its own journey, as if it might well be the last. This was the lesson of the earthquake.

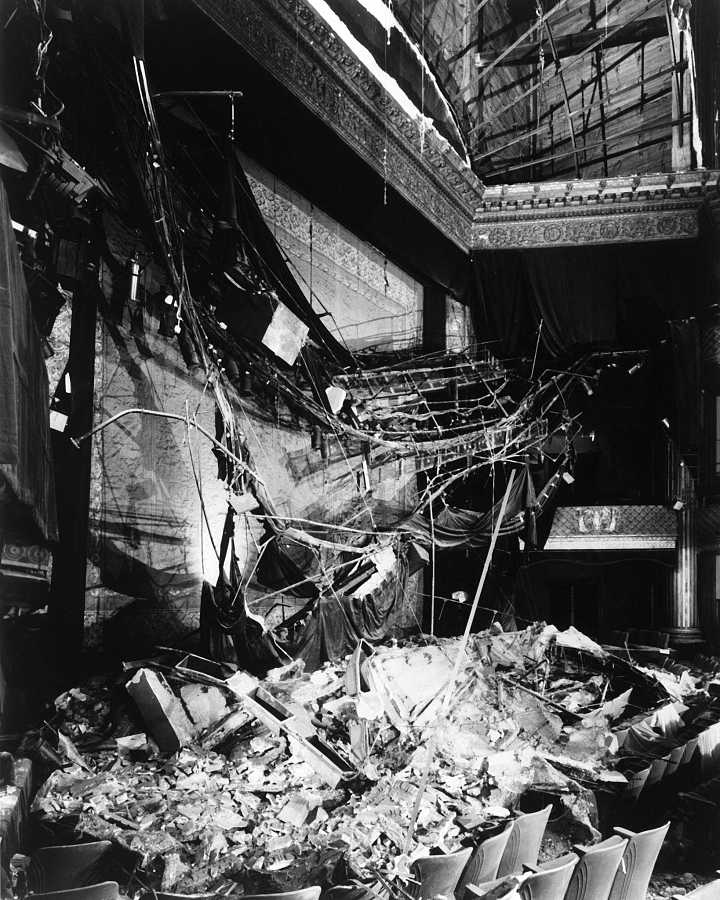

“It’s like seeing a dear friend in intensive care,” the actor Raye Birk said about the Geary Theater as it lay in ruins after the Loma Prieta earthquake. Indeed, the first glimpse of the destruction was an awesome sight. I can’t remember upon which of my early visits to A.C.T. I was taken inside the ruined building, but I do remember how astonishing it was. And beautiful, in a kind of horrifying way. Truth be told, in addition to my love of talking, I love ruins. In fact, since the second grade I had longed to imitate Heinrich Schliemann, excavator of Troy, by reading Homer and finding lost cities on the plains of Greece. I majored in ancient Greek at Stanford with the express purpose of preparing myself for this lifelong adventure, after having spent my teenage years in the Four Corners of the American Southwest, digging up Anasazi ruins in the baking heat under the guidance of an archaeologist named Arch from the University of New Mexico on whom I remember having an enormous crush.

I loved the puzzle-making aspect of archaeology—the process of finding isolated clues that, if pieced together correctly, could yield lost information about human behavior from remote times and places. There was something about it that allowed my imagination to run wild—and that sensation came back to me in powerful waves as I beheld the ruins of the Geary Theater in November 1992 on one of my first visits to A.C.T.

The stories of that fateful October day were already legion. George Coates’s experimental production Right Mind, a version of Alice in Wonderland, had just opened to strong reviews. It was the year of the all–Bay Area World Series, and anyone in town who could snare a ticket had rushed to Candlestick Park to watch. The game began innocently enough. The city was calm. The Geary was momentarily quiet—A.C.T.’s stage crew had just left the theatre for the dinner break before coming back to set up for the 8 p.m. performance. The many children enrolled in the Young Conservatory were arriving across the street for their afternoon classes. As often seems the case on days of epic disaster, the skies were blue and clear on Oct. 17, 1989: a gorgeous afternoon promising a happy ending.

At 5:04 p.m. the rumbling began. Captured on ABC News footage is Al Michaels, in the midst of a play-by-play account of the World Series game, slowly realizing that an earthquake of massive proportions was taking place all around him. Within minutes, a span of the Bay Bridge had collapsed, half the Marina district lay in disarray, buildings all down the Peninsula (including many in the Quad of my beloved Stanford University) had been shaken beyond repair, and the auditorium of the magnificent 1910 Beaux Art Geary Theater was covered in rubble.