On the first day of rehearsals for It Shoulda Been You, David Hyde Pierce had the company play a game of volleyball.

He learned this trick from his work in La Bête, when the cast, crew and ushers would turn the Music Box Theatre into a volleyball court before each performance. On opening night, Marian Seldes arrived early and sat in the theatre and watched everyone play. Days later, she sent Pierce a message that said, “I felt so privileged that I got to watch the volleyball, and then watch the game continue onstage. “

And now the game will go on every night at Broadway’s Brooks Atkinson Theatre, where It Shoulda Been You opens on April 14. The show follows the behind-the-scenes shenanigans at an interfaith wedding, where the sister of the bride is struggling with living in the shadow of her ultra-perfect younger sibling.

Pierce, however, never intended to direct the show—or even to direct at all. He attended readings and workshops of the musical because his husband, Brian Hargrove, wrote the book and lyrics (Barbara Anselmi wrote the music), but Casey Nicholaw was on board to direct at that point. Then Nicholaw got offered a little project called The Book of Mormon.

The show was stranded without a director, and Pierce found himself in a spot. He’d watched the development process to support his husband, but with Nicholaw out, the project lacked a bold-faced name that could attract commercial producers. As the team was gearing up for the show’s premiere at New Jersey’s George Street Playhouse in 2011, Pierce decided to lend his name and try his hand at the helm.

“I was a little nervous about it because I didn’t want people to say the show went up because I was married to David Hyde Pierce,” Hargrove confesses. “People are going to think what they think, but that’s not what happened. I’m proud of the work.”

Pierce, for his part, discovered that he loved directing. After the George Street baptism, he directed a 2012 production of The Importance of Being Earnest at the Williamstown Theatre Festival (where he’d gotten his start as a non-Equity actor), in which all the characters became Damon Runyonesque. Next was a production of Christopher Durang’s Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike at Los Angeles’s Mark Taper Forum, which Pierce took on after the late Nicholas Martin fell ill and asked him to step in. He’s also gearing up to direct a new David Lindsay-Abaire play, Ripcord, at Manhattan Theatre Club in the fall.

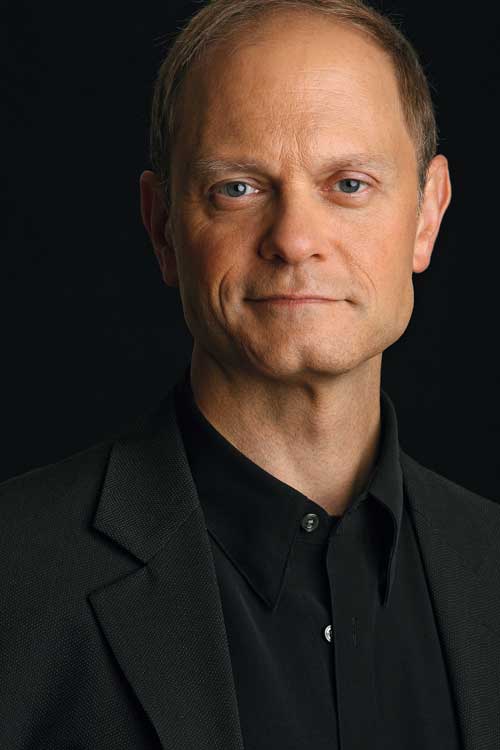

“Once I started directing, I realized that a big part of my actor’s brain works as a director,” Pierce confides on his lunch break from rehearsal at New 42nd Street Studios. In fact, that’s what his cast likes most about him—and after a while, they start to sound like a broken record.

“He’s very specific and easygoing and keeps a nice feeling in the rehearsal room,” says Tyne Daly, who played Lady Bracknell in Pierce’s Earnest. “Because he’s an actor, he has the language to help an actor make a little adjustment.”

“It’s fun to see him direct, because he’s an actor’s director,” confirms David Burtka, who plays the groom. “You can see the propellers moving in his mind as the different characters.”

“He’s the best director I’ve worked with, only because I feel like he’s coming at it from an actor’s perspective,” chimes in Lisa Howard, who plays the sister of the bride. “He knows just what to say to have you think about it a different way for a different result.”

“David is an actor himself, so his way of communicating with actors is very real and simple,” offers Montego Glover, who plays the maid of honor. “He sees the big picture, but he can focus. He’s very patient and he’s a good leader.”

You get the picture.

American Theatre sat down with the star of stage and screen to talk about his theatre roots, making the transition behind the table and what’s next.

SUZY EVANS: So It Shoulda Been You at George Street was your first time directing professionally, but I read somewhere that you did some directing while you were studying at Yale.

That’s right, I did. You know what? I actually had done more directing than I realized, because aside from one-offs in elementary school, I went to a summer camp up in New Hampshire, called Kabeyun, and they would do a Gilbert and Sullivan show every summer, and I directed H.M.S. Pinafore and The Sorcerer. And then I went to Yale as a musician. They had a Gilbert and Sullivan Society there, so my freshman year I acted in a production of Pinafore and ended up directing Princess Ida the second term of my freshman year. I think it actually turned out okay, as I recall.

You’ve never directed for television?

No, that doesn’t interest me. I started out in the theatre, and it’s what is in my bones. I’m not one of those people that had an immediate attraction to the camera. When I was doing “Frasier,” our second year was the first year of “Friends,” so I observed our director Jimmy Burrows, who is a great television director and also a fine theatre director, working on the early episodes of “Friends” to see if television directing was something that interested me—and it just didn’t. One of the things I learned from Jimmy, which I always have in the back of my mind in this show, was to set a goal for every single person in the cast, no matter how small their part—there needs to be at least one thing that they can’t wait to get to the theatre to do, one thing in the show. And I just loved that idea.

What has it been like collaborating with your husband on It Shoulda Been You?

The whole process has been very good, and now that we’re on Broadway, with the heightened excitement and expectation and pressure, we’ve found that it’s still a very good collaboration. The difference between Broadway and George Street is that more of our discussions now happen at three in the morning instead of during normal business hours. Broadway really makes you realize how you’re against the clock when you’re putting on a production, because there are financial consequences to every choice you make. Brian’s experience as a TV writer is vital, because in doing half-hour television, you have the ability to look at what seems to be a finished product and to say, “Oh, I see it needs a whole new second act!” And then to just go off and do it. That’s what he does. He has no problem in throwing stuff out or changing things.

Nicholas Martin asked you to step in and direct Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike at the Ahmanson. What was it like to direct a show you had also acted in?

That was a great opportunity. I was working with some new actors—Christine Ebersole, Mark Blum, David Hull—and I had to find the balance between shepherding what Nicky had done and, at the same time, allowing these new actors to find their own way. It didn’t feel like just replicating something that had been done already. It was challenging to have a sense of the shape of a show, because you’ve had the chance to do it, and then work with actors who are new to it and might have completely different instincts. Because it’s a good play, it completely can stand that kind of different interpretation.

Do you ever want to get up onstage when you’re directing?

I don’t get up and demonstrate for the actors, but sometimes I do have to get up onstage to think through something. I don’t know if that’s kosher or not. But it’s not to demonstrate—it’s purely to facilitate my own brain and figure out what I would do in that situation. I’m very respectful of actors and of their different processes. In fact, the biggest learning curve for me, which was a surprise, was not the technical stuff—I assumed, gosh, lighting, what the hell? I was surprised at how I was able to accommodate that new world of technology. But it’s been learning how to talk to actors (or most important, when not to talk to actors and to let them do their thing) that’s been what I’ve really had to learn, because they’re not me. You hope that as a director your sensibility shapes and permeates a show, but having cast all these amazing people, you want it to bubble with their energy and their different points of view.

A lot of your theatre work—both directing and acting—has taken place at nonprofit theatres across the country. What do you love about working in regional theatres?

I got a lot of my training, from 1983 to ’85, working at the Guthrie [in Minneapolis]. In fact, I met Harriet Harris [who plays the mother of the groom in It Shoulda Been You] in 1984 in a production of Tartuffe at the Guthrie, and then in 1985, I went back and did the whole season. The Guthrie was doing repertory theatre, where you’d be rehearsing two plays during the day and performing a third at night, and it was incredible training. That kind of immersion experience teaches actors to play all different kinds of roles in all different kinds of plays. I also think of the nurturing aspect of regional theatre. When we did It Shoulda Been You at George Street, David Saint, the artistic director, gave me such support and such protection as a first-time director—that’s the kind of thing that you just can’t get in the commercial theatre

You have a cast of great comic actors, but are there tricks to directing comedy?

It’s about music; it’s about rhythm; it’s about where the space and the sound are. If you have a musical sense, you can hear those things or even see those things—it translates to visual comedy. I have an advantage in having worked with so many different kinds of directors that I know there are no rules in what you can and cannot say to actors.

Any directors in particular come to mind?

I remember that a month after we opened in Peter Brook’s production of The Cherry Orchard at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, Brook came and gathered the cast together—quite a cast, Brian Dennehy, Linda Hunt—and he said, “The show has grown in some ways, and it’s diminished in some ways. The show has grown in cheapness and vulgarity, and it’s diminished in actual human behavior.” And we were all like, “Oh that isn’t what we meant to do!” There’s a parallel story with Mike Nichols directing Spamalot. He came back a few months into the run and gave us the note, “When you know exactly how to get your laugh”—as he put it, “when you’ve found your favorite squeak and turn”—he said, “don’t do that. Try other things instead and see what happens.” As an actor, that unlocked something for me, which is the idea that there isn’t, no matter how good you think it is, only one way to do something.

I want to see actors who are engaged with each other. One of the greatest compliments I ever got came when I was doing a two-person play with Uta Hagen in Los Angeles—she wasn’t directing, but I learned so much from time spent with her. After the show, someone said, “It wasn’t like watching a play; it was like we were eavesdropping.” Even in the biggest musical, I think that can still be the case.