Challenge

To creatively enlist many artists on a project, enliven programming, and expand on the short-play festival. Plan: Select a music album and sign up playwrights to write short plays inspired by the album’s songs.

What Worked

Keeping the music selections within the mission; attracting press and audiences; working with both new and familiar artists.

What Didn’t

Cohesiveness is difficult to maintain; staying organized with tech and communication is taxing.

What’s Next

Continuing the tradition every few years.

Ten-minute-play festivals: Can’t live with ’em, can’t live without ’em. Such events tend to be delightfully endearing and inclusive, yet damningly random and scattershot. While short-play festivals have the advantage of including lots of artists and ideas—and are a sure-shot recipe for generating income, excitement and attracting audiences—they nevertheless often have a slapdash quality to them. That can be true no matter how purposefully planned they are, especially when the festival doesn’t have some overarching theme or structure.

Enter Chicago’s Tympanic Theatre Company, founded in 2006 and dedicated to putting on new work with a fantastical edge. Six years into the theatre’s existence, its members wanted to try something new that would challenge them aesthetically and involve a host of collaborators, new and old. “It had been a while since we’d had a show with a huge cast, and there was a sense of wanting to ‘get the band back together’ and do a project that would involve a lot of people,” says Tympanic artistic director Dan Caffrey, who is also a playwright and senior staff writer for the music site Consequence of Sound. “I thought, ‘What if we did a play festival based around an album?’” Caffrey recalls.

From there, Caffrey and his cohorts tossed around album ideas, eventually settling on Bruce Springsteen’s 1982 classic Nebraska. “You need to pick a band that has enough of a history and enough classicism about it, but that’s not overdone,” he advises. (For example, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, though ripe for interpretation, feels like already well-trodden territory, Caffrey reasons.) Once Tympanic selected Nebraska, the group sought out 10 scribes from around the country who would write short plays based on each of the album’s 10 songs.

The result was Deliver Us from Nowhere, which bowed in 2012 at Chicago’s Right Brain Project, involving 10 playwrights, 10 directors, some 20 to 30 actors and four musicians. The show was financially successful. “It was great to go grand and big,” remarks Tympanic marketing director and literary manager Chris Acevedo, who adds that Right Brain Project’s intimate setting provided a perfect home for the ambitious festival.

For its second music-inspired play fest, Tympanic tossed around albums by Wilco and the Decemberists but ultimately decided on Radiohead’s 1997 album OK Computer, as opposed to the band’s more abstract Kid A. “Songs by the Decemberists are so narrative-driven that the story is pretty much done by the end of the song,” observes Caffrey. “You could argue the same for Springsteen, but there’s still enough mystery to his songs that you’re left wondering.” Acevedo chimes in, “We try to stress to the playwrights that we want them to be inspired, but not necessarily write a literal narrative or a verbatim adaptation of the song.”

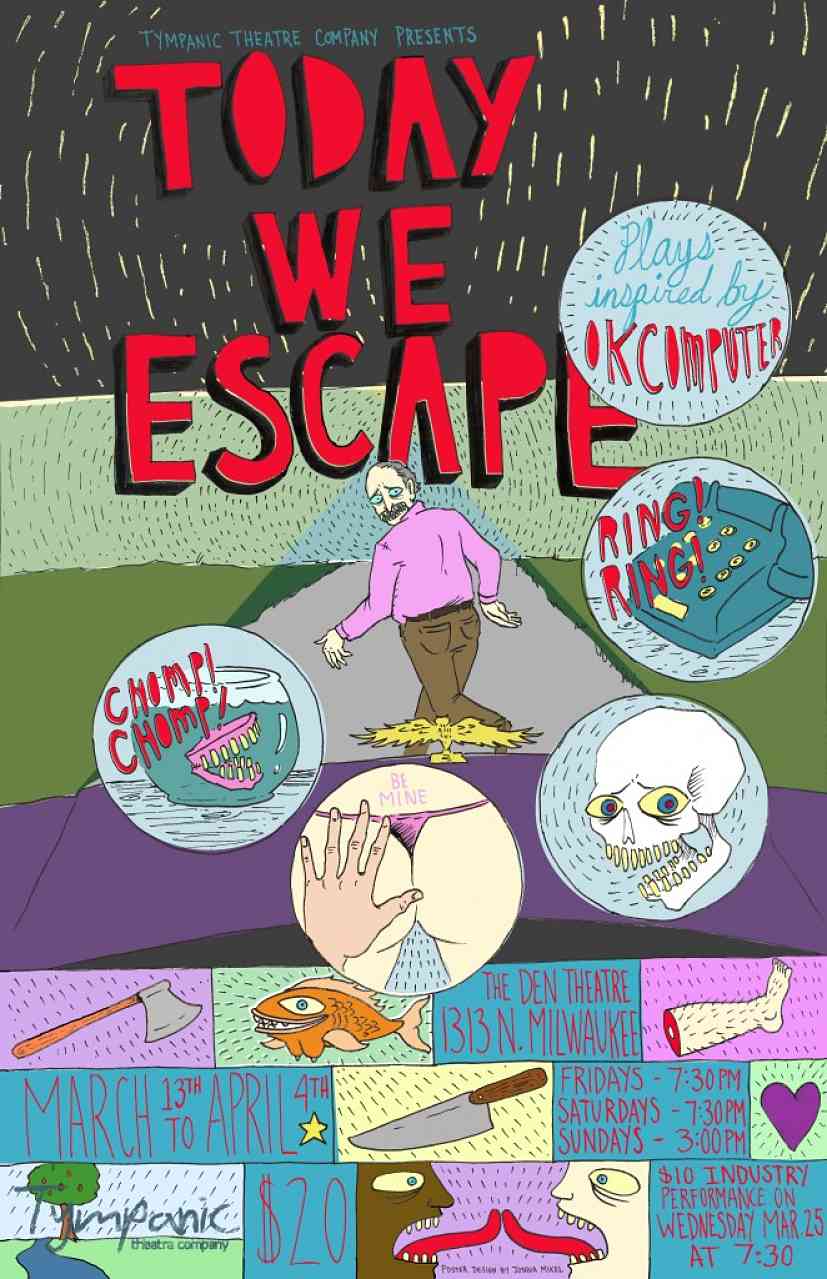

For the Radiohead-inspired Today We Escape, which runs March 13–April 4, Tympanic generated a list of some 25 local playwrights and over the course of three meetings whittled the list down to 12—that included a combination of writers they’d worked with before and first-timers. Once the playwrights were chosen in late October, they submitted their top three song choices and wrote a short pitch for each song. Tympanic then assigned the songs, and the plays were due at the end of December. Directors, enlisted by Tympanic in a similar process, selected their top three plays in early January and a two-day round of auditions followed. “It’s kind of like putting a Rubik’s Cube together,” says Acevedo.

Part of Tympanic’s success with these music-inspired play festivals is due to careful selection of albums that fall within the company’s aesthetic and mission. “Tympanic’s emphasis is on new work that transports the audience to another world. Often our work has fantastical or absurd qualities,” says Caffrey. “For Nebraska we got a lot of ghost stories.” In the case of OK Computer, themes of paranoia, escape and a dystopian future took hold. And yet the stories themselves differ greatly.

Justin Gerber’s The Last Show (inspired by “Fitter Happier”) starts off with a late-night-show host and his guest chatting and laughing but turns into something scary; Scott T. Barsotti’s Wavelength (based on “Climbing up the Walls”) presents a veteran who discovers she has an unusual talent she’s not so sure she wants; Joe Zarrow’s Roll (drawn from “Let Down”) features a Dungeons & Dragons group that is breaking up but willing to have one last dungeon crawl.

“By virtue of being based on the same album, the plays often strike similar chords in terms of underlying mood,” points out Ted Brengle, whose B.E.M. (inspired by “Subterranean Homesick Alien”) focuses on a middle-aged dermatologist removing slivers of glass his patients believe were implanted by extraterrestrials. “The ability to effortlessly establish a greater sense of artistic coherence for the evening as a whole, without sacrificing the ability of the playwrights to go off in bonkers directions all their own, is quite wonderful and pretty rare,” he observes.

Short-play festivals thrive when writers are given both constraints to work against and the freedom to pursue what they wish within those constraints. Randall Colburn, whose Terry was inspired by “Paranoid Android,” actually draws on a character he created in his previous 2011 Tympanic production, Verse Chorus Verse. “The plays I’ll write for a festival like this tend to eschew story for atmosphere. You only have a few minutes, so I’d rather try to inhabit a world than explain it away,” Colburn says.

Caffrey and Acevedo point out that part of the cohesiveness of such events comes during tech week, when musicians arrive and introduce their own original tunes that will greet ticket holders as they arrive and serve as transitions between the plays. This music is inspired by the plays themselves, so audiences shouldn’t necessarily expect to hear Nebraska or OK Computer—instead, they’re invited to relish musical variations on a theme.

Organization and scheduling are essential for a project of this scope. “Intermission should be whenever you’d flip the record,” Caffrey reasons. “Short-play festivals are money-makers and can involve a lot of people, but that shouldn’t be the primary reason you do them. And don’t just do this because you like a band, either—do it because you’re trying to reinterpret this cohesive piece of art.”