Soho Rep’s tiny black-box space, tucked inside a nondescript storefront on Walker Street in Tribeca, is a living artifact of a bygone era when Off-Broadway theatres were scrappy hotbeds of invention. Founded in 1975 by Jerry Engelbach and Marlene Swartz in a former hat warehouse on nearby Mercer Street, the company has been in its current space since 1991. Artistic director Sarah Benson has been at the its helm for the past seven years and has in that time garnered a reputation—and an impressive cluster of critical accolades to bolster it—for staging fully immersive works that often resist simple categorization.

“In a way, we treat the space site-specifically, even though it’s a black-box theatre,” Benson explains over lunch at a bustling Italian restaurant in Soho. It’s early November and the first truly cold day of the year. The theatre—just a couple of blocks south of us, where debbie tucker green’s generations, a 30-minute, choral meditation on South African life is now playing (it closed Nov. 23)—is often physically unrecognizable from production to production.

“I’m not very interested in scenery. I’m much more interested in architecture. When I’m hiring a designer, I want them to design the room and not onstage scenery. I feel like designers know that, so the design element creeps farther and farther out. In generations, it’s all the way to the front door,” Benson notes, referring to the colorful metal panels that line the building’s interior walls from the street entrance, through the small box-office area and into the space itself. “Arnulfo Maldonado really designed it right.”

Just as notable as the panels is what’s underfoot: 20,000 pounds of reddish dirt covers the floor, sourced from a befuddled Staten Island man who’s used to supplying baseball fields. “I’m in the wrong place. What do you need 20,000 pounds of dirt for?” Benson remembers him saying as he pulled his truck up to the theatre.

Benson called an architect friend, as she often does during productions, to inquire if the floor could bear the weight. (It could, to her delight.) She’s gotten used to asking out-of-the-box questions. When she was working on Blasted, her first production in the space and Soho Rep’s most acclaimed production to date, a friend told her, “You don’t have to be polite with the space. Just replace the structure that you’re cutting out.” That proved useful advice for Benson as she sawed through the theatre’s rafters.

“The design process for me is a huge way into the world of a play, and helps me figure it out,” she proffers. Having grown up in Southern England, Benson, now 36, has fond memories of practical projects undertaken with her father, an engineer who makes steering wheels for ships. “I remember us building a water clock and calibrating it. We were always doing things together. His workshop was always a fantastical place—I used to love going out and seeing what he was doing, and I’d make a lot of stuff with my mom, as well. My sister’s a musician and lives in Norway now, and it’s so weird because no one else in the family is in the arts. Yet there was always this interest in making stuff, and that has stayed with me. It’s one reason for my interest in the holistic theatre experience.”

For Benson, as for many, the immersion in theatre began in high school—and not auspiciously. “The school play—that’s how you participate in theatre at that age. For me, it was just truly agony. I would constantly screw up and forget props, or show up at the wrong entrance.” She laughs now, but it’s clear that her actorly ineptitude was a source of pain and confusion; her difficulties culminated during a fateful performance of Guys and Dolls: “For the scene where Adelaide brings the present, I showed up without the present. It was that level of terrible.” Luckily, she had a theatre teacher who advised her there were other ways to participate.

“It was a massive relief” to find an alternate course, she allows, “because I so enjoyed the community of theatremaking. After high school, I started choosing plays and putting them on, and very quickly I found that this was my world.” As she was making those early forays into directing, Benson consumed all the playscripts, books on acting and directing theory, and accounts of theatre history she could get her hands on.

She remembers going into a bookstore in London on a search for photos of theatrical productions and discovering a book she still refers to—designs by Jocelyn Herbert, who’d worked at the Royal Court Theatre on new material by Samuel Beckett and John Osborne. Up to this point, her experience seeing professional theatre was limited to a few Andrew Lloyd Webber shows in the West End. “I remember that at Starlight Express, the one on roller skates, I was by far the most interested person in my family. My dad would announce as the curtain rose, ‘It’s so nice and warm and dark in here, I’m going to have a sleep.’”

Benson continued her makeshift education in theatre while majoring in English literature at King’s College in London, in part by involving her musician sister and their friends in the architecture and visual arts worlds in homemade productions. “That was a formative time—I realized that I still didn’t know how to work with actors, and although it fascinated me, I felt lost. Actors were a mystery to me, and I felt much more comfortable in the design world.”

An American she worked with in Edinburgh opened her eyes to the world of MFA programs. “In the UK, they don’t have that kind of system at all—the whole training process is more cerebral. He said I should check out Brooklyn College. I had never heard of it at the time, but I came over and met with Tom Bullard, who runs the program, and I was blown away.” Shortly afterwards, Benson landed a Fulbright scholarship, and during her third year stateside scored an internship at Soho Rep. That turned into running the theatre’s writer/director lab the following year. And, in short order, she became one of the youngest full-fledged artistic directors of a major theatre company in the U.S.

Benson’s career has had the kind of fast trajectory most directors can only dream of. She counts Bullard, a founding director of the Manhattan Theatre Club, as a dear friend and mentor. “We have opposite taste in plays, but I was immediately like, ‘He’s genius!’ He has this crazy intuitive understanding of actors and how to work with them.”

That relationship clearly fed into Benson’s growing facility with actors, which has blossomed in her years as a director: She has harnessed subtly radiant performances from the likes of Marin Ireland, Zoe Caldwell and Larry Pine, among others. Still, she loathes the audition process. “I love meeting new actors, but I find auditions to be a strange situation. I prefer doing a lot of readings and workshops and corralling a company around a project.

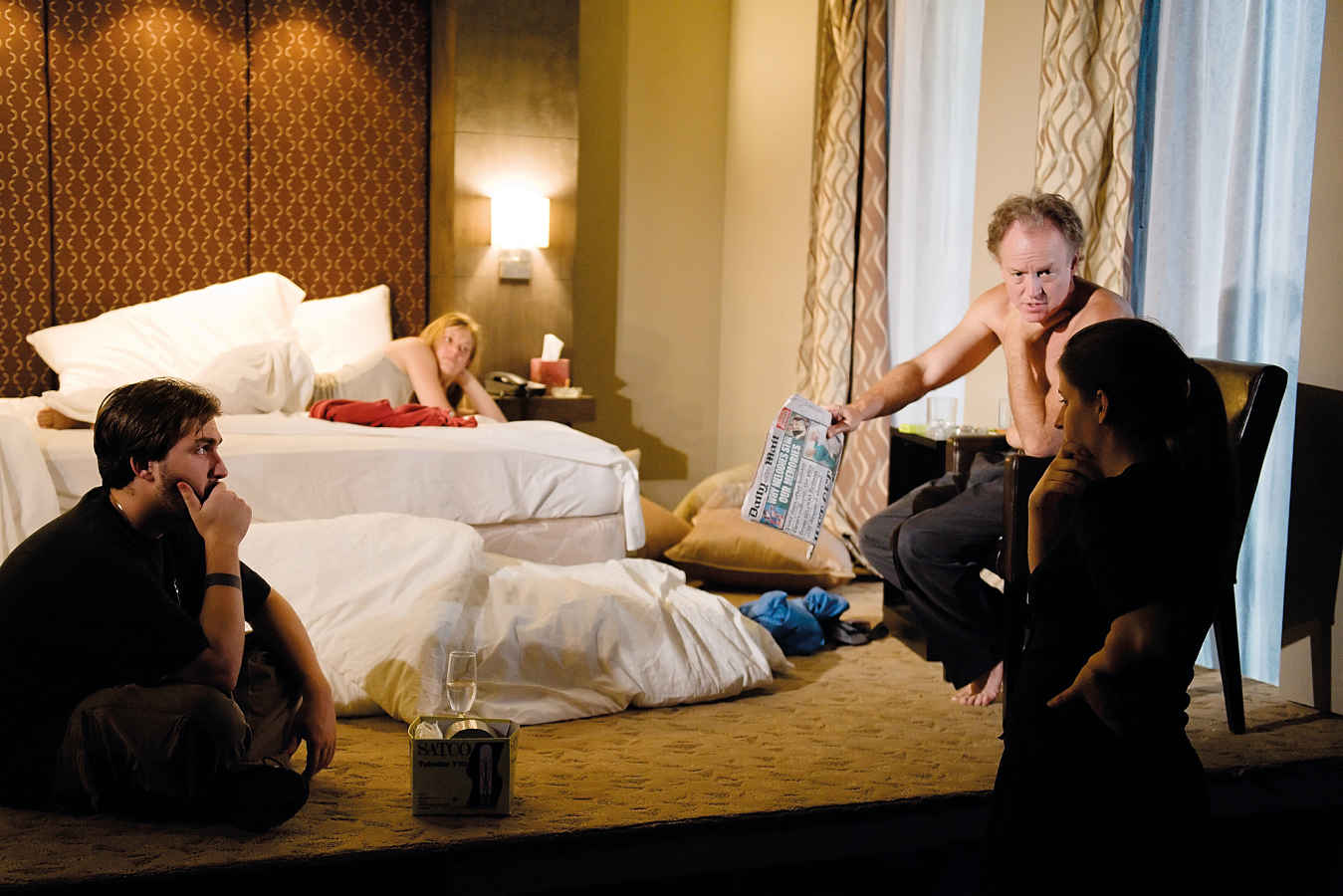

“I also find myself taking a lot of blind leaps,” Benson confesses. “When I did Blasted, there were no auditions. Marin Ireland had instigated the project.” Benson asked Ireland who she thought should play opposite her as the bigoted tabloid journalist Ian, and the actress immediately named Reed Birney. “I had never seen Reed do anything like the role of Ian,” Benson notes, “but I knew, as he would say himself, that his forté had always been playing like a nice dad who lived next door. But this was playing a racist bigot, you know?” Birney had his own reservations about the role. “I don’t know,” he told Benson when she offered him the part. “I take my clothes off on the first page. I don’t know.”

It all worked out. “That role is more interesting if it’s played by someone we can associate with,” Benson reasons, “and Reed just exudes compassion. But I didn’t know what was going to happen.” For some directors, not knowing could cause hesitation, but for Benson it’s fuel. “I’m regularly trying to put myself in an uncomfortable position and challenge my own assumptions,” she says. “I try to find work that I don’t know how to do—honestly, that’s the work that I’m most fired up by.”

Benson’s sees her roles as director, artistic director and producer as fluid, bleeding into each other. In rehearsals, she makes a point of declaring that she’s just another artist in the room and that her notes don’t have some kind of divine weight. “I explicitly say to people that I don’t necessarily expect my ideas to show up onstage. Don’t take my notes if you don’t think that they’re good for you.”

Producing every play that Soho Rep commissioned “wasn’t a conscious mission or anything,” Benson notes. “We just did it.” She is proud that when playwrights get the green light for a Soho Rep commission, they know their work won’t be strangled in development hell. “We want the artist to make something for our space and not be second-guessing whether or not it will be produced.”

As driven as she is, there’s a playfulness about Benson, the kind that wants to upend and challenge notions of what’s possible in the theatre. “I’m interested in destabilizing my own fucked-up perspective and assumptions,” she says with a grin. “One of the reasons naturalism is really hard for me is because I feel like it’s a pretty remarkable thing that two people can sit in a room and talk—that we’re here at all and we’re not reduced to a gaseous ball flying through the universe. Naturalism tries to normalize that for me, but I’m interested in heightening the strangeness, wonder and ugliness of how crazy the world is.”

She emphasizes that there’s no “house style” at Soho Rep and that, despite her love of design, she hates the very concept of “style.” That aversion can be detected in her award-winning staging last spring of Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’s An Octoroon, a wild deconstruction of history, form and the ideas we tie our identities to: The fourth wall comes literally crashing down in the middle of the play, leaving audiences nonplussed and giddy. “I spend the whole rehearsal process trying to get away from images that immediately present themselves,” Benson says of that gambit. “I’ll prepare kind of obsessively and then ditch it all.”

In an unprecedented move for the company, An Octoroon is being remounted this month at Theatre for a New Audience in Brooklyn. Benson sees the transfer as an exciting opportunity to reinvestigate the material. The audience is referenced often in the play, and Benson pays close attention to the dynamics that engenders.

“I love visual art, TV and movies, but I’m looking for work in the theatre that has to exist in that medium—which for me means work that’s acknowledging that it’s a live-before-an-audience experience, and therefore a civic experience,” she reasons. “The audience, by being there, is completing the experience. Who we’re making the work for is as important to me as what we’re making.”

Christopher Kompanek writes regularly for this magazine.