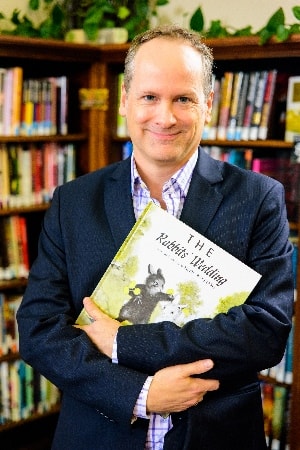

SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH: Who ever thought that a children’s book about rabbits could stir up controversy? But that’s what happened in 1958, when artist Garth Williams (best known for his illustrations in Charlotte’s Web and Little House On the Prairie) released a book called The Rabbits’ Wedding.

It was a seemingly innocuous topic: Two rabbits were getting married in the forest; one was white, the other was black. Williams didn’t intend for it to be political, but for segregationists in the South during the period, the book was a metaphor for racial integration. One Alabama senator demanded that the book be removed from all library shelves in the state. One librarian, Emily Wheelock Reed, defended The Rabbits’ Wedding and refused the order.

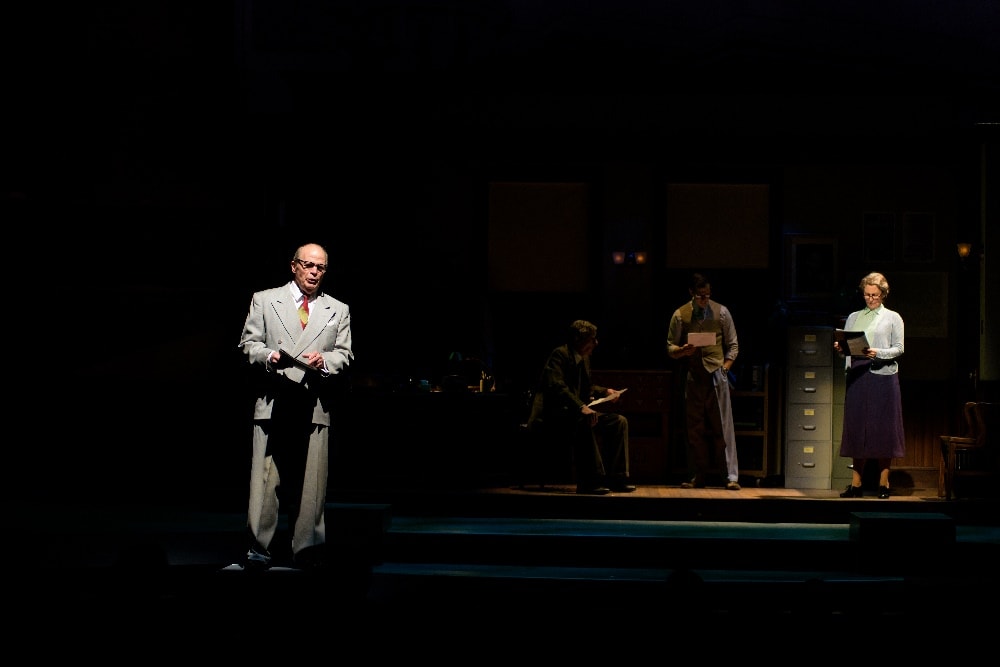

That conflict is the subject of Kenneth Jones’s play Alabama Story, currently receiving its world premiere at Pioneer Theatre Company, where it’s running through Jan. 26. It is the first play from Pioneer’s one-year-old Play-by-Play new-works reading series to receive a production.

Besides receiving raves from local papers, Alabama Story has renewed interest in Williams’ book. “The county library has ordered 26 copies of The Rabbits’ Wedding,” Jones says proudly in a phone interview.

The New York City–based journalist-turned-playwright is spending the month in Utah while his play is running. We spoke to him about life on the other side of the curtain, and about how recent censorship debates, not to mention the film Selma, have made the play seem all the more relevant.

Did you read The Rabbits’ Wedding growing up?

I didn’t. I knew Garth Williams’s work because we all have some connections to the books that he illustrated, like Little House on the Prairie, Stuart Little and Charlotte’s Web—iconic children’s books. I learned about this because I read Emily Reed’s obituary in May 2000. I instantly thought it was a play. It was about a librarian at risk and a bullying senator. Those were incredible opposites and incredible forces. They’re both tied by a love of books.

So ironically, even though the senator, E.W. Higgins, wants the book taken off the shelf because it’s about a black rabbit that marries a white rabbit, he still loves books. I tried to humanize him a little bit and share what his connections to books were. And of course the librarian is connected to books because she’s a librarian; she’s always been passionate about books. All thse opposites really attracted me: She’s from the North, he’s from the South. She’s a woman, he’s a man. Young, old, black, white, insider, outsider, love and hate. That all weirdly appealed to me when I read this obituary.

I also knew that Garth Williams would be a character; he would narrate it. The play owes a debt to Thornton Wilder in a big way—we’re all touched uniquely by Our Town, and there’s a lot of Thornton Wilder in this play. And Garth Williams is our guide; he plays multiple characters, fills in the blanks.

I saw the play when it was read at Alabama Shakespeare Festival, and I remember that there was also a fictional story in it as well.

I didn’t want to write a docudrama, I didn’t want to write a movie of the week. I wanted to show how the political and public related to the private and the personal stories. As the senator is talking about integration and segregation, I wanted to explore what it meant for regular folks.

I created this fictional story that’s a reflective story, that glances off the main story, about Lily and Joshua, who are in their 30s. They reunite by chance the same year all of that library business is happening in Montgomery, Ala. They were childhood friends and they talk about the events in their past and they rehash the pain and the affection of their past and where they are now. We very much weaved that story into the library story, but mostly those characters never meet, those worlds never collide.

At the very end, Joshua gives Lily a copy of The Rabbits’ Wedding as a gift of forgiveness, because forgiveness is a huge part of the play. I’ve often said that the play is about how characters are tested in times of change, and that happens in both stories. Saying I’m sorry is really important to this play, because the senator is never wrong and never sorry.

Considering that it’s based on a true story, did you embellish or dramatize the real-life events?

It roughly follows the timeline of the year of this controversy. It starts at the beginning of 1959 and ends at the beginning of 1960. Emily Reed left in 1960. I said that it’s inspired by facts, but it’s a fictional account. The senator challenged her in budget meetings when she was seeking to have her budget renewed for the library, and there are no public records of those meetings. So I created a kind of courtroom drama at the budget meeting where she has to defend herself, but that’s fictional.

But I do draw a lot from the newspaper reports of the day, there were some lines directly lifted from newspaper reports where the senator says “This book ought to be burned. There’s no room for any other opinion but ours, our enchanted Southern kingdom must be preserved.” Crazy, bigger-than-life things that you think are made up by a dramatist, but they’re right there in the newspaper and that’s what he said.

And Emily’s really eloquent comments about librarianship were also pulled from articles. At one point she says, “A librarian must be a repository of all sides of the question.” And, “I believe that the free flow of information is the best means to solve the problems of the South, the nation and the world.” I mean, that’s her real comment and it’s so profound today, with what’s happening in Paris and what’s happened all over the world. Books are still being pulled off of shelves and challenged by politicians and conservative groups and individuals all over the country. It happens every day.

Is censorship in libraries an issue in Salt Lake City?

A couple of years ago in Davis County, Utah—which is nearby—there was a book called In Our Mothers’ House by Patricia Polacco that was challenged by politicians. They tried to take it off the shelves. It was about a lesbian couple raising a multiracial group of kids. This has been brought up to me a couple of times, that there are challenges here. Obviously it’s a conservative state; the Mormon Church is very powerful here.

Do all of the headlines about race and censorship give the play more resonance for you?

It definitely does. The more I talk to librarians here, the prouder I am of the play. I talk to a librarian with tears in her eyes, saying, “I feel like you’re in my library, I feel like you know what I do.” Our first reading here at Pioneer, the state librarian of Utah was in the room. It feels very relevant across the board in many ways. It’s about censorship, it’s about freedom to read, it’s about civil rights, it’s about freedom of expression, and that’s all kind of alive at the moment.

I think it’s just in the zeitgeist; the play just happened to coincide with all these terrible, awful things that are happening in the world, and some great things as well, like Selma and the 50th anniversary of the Voting Rights Act and the Civil Rights Act.

You’ve spent your career interviewing artists, how does it feel now to be on the other side?

I’ve been a secret dramatist from the beginning. I was always afraid I wouldn’t make money as a playwright. So I went into journalism and I threw myself into journalism and was really passionate about it and still love it. The play is a result of me reading newspapers and being passionate about newspapers; I came across the story that way. I hope it’s a second act for me, to really fulfill a longtime goal of being a working dramatist.