NEW YORK CITY: Are you in the mood for fast food or a multi-course meal? To Taylor Mac, that’s the difference between short, 90-minute plays versus what he’s going to be undertaking at this year’s Under the Radar Festival: a six-hour performance titled A 24-Decade History of Popular Music: 1900–1950s.

“You go to the five-course restaurant, you dress up, you plan for it, you put it on your calender,” Mac says over the phone. “If you’re just picking up a burrito down the street, you don’t plan for that.”

It’s the difference, in short, between an event and a quick romp. “The audience invests more than they would normally invest. You prepare, you think about what you’re going to be doing, you think of all the stuff that you wouldn’t normally think about when you go to see a [shorter] show.”

Theatregoing in January in Lower Manhattan can be a durational event in itself, given all the festivals, ranging from the Public Under the Radar to COIL Festival, PROTOTYPE, American Realness and (new this year) Squirts (don’t Google that last one at work). These festivals take labels like theatre, opera, concert, art installation and mix them together in a blender until what comes out is a hybrid of everything, defying description.

As Mac’s show proves, another category being stretched beyond recognition at this year’s festivals is time. There are performances ranging from five minutes (Reggie Watts’ Audio Abramovic) to six hours (not only Mac’s show but also Temporary Distortion’s My Voice Has an Echo in It at COIL).

Previous years have included durational performances (Nature Theatre of Oklahoma‘s eight-hour Life & Times: Episodes 1–4 in 2013, for instance). But this month, we counted four performances that are vying to test the endurance (and bladders) of both performers and audiences: the pieces by Mac and Temporary Distortion, as well as Anne Imhof’s Deal, 2015 at American Realness and The Commentators from Stan’s Cafe at UTR (the latter two clocking in at four hours).

For A 24-Decade History of Popular Music: 1900–1950s (Jan. 13–25), co-presented with New York Live Arts, Mac will be examining the first half of the 20th century through the lens of popular music, with an hour devoted to each decade. It’s part musical history lesson, theatre and cabaret; it’s also an examination of LGBT presence through the ages. Mac says he was inspired in part by a 1987 AIDS walk he attended in San Francisco when he was 14.

“[I wanted] to try and find queer agency throughout history, and as a result reframe things, and invent things, and make a queer historical event,” says Mac.

The concept sounds heady but Mac promises it’ll also be fun. “We have the audience move at certain points,” says Mac. Previous performances of the work included dance lessons and a conga line for the audience, as well as opulent, bedazzled costumes for Mac. “It’s about trying to figure out way to give them enough physical variety so they don’t just become mush.”

That doesn’t mean that he expects audiences to be completely alert for the entire six hours. “If you don’t glaze over a little bit, there’s something wrong with you, or you’re on speed.”

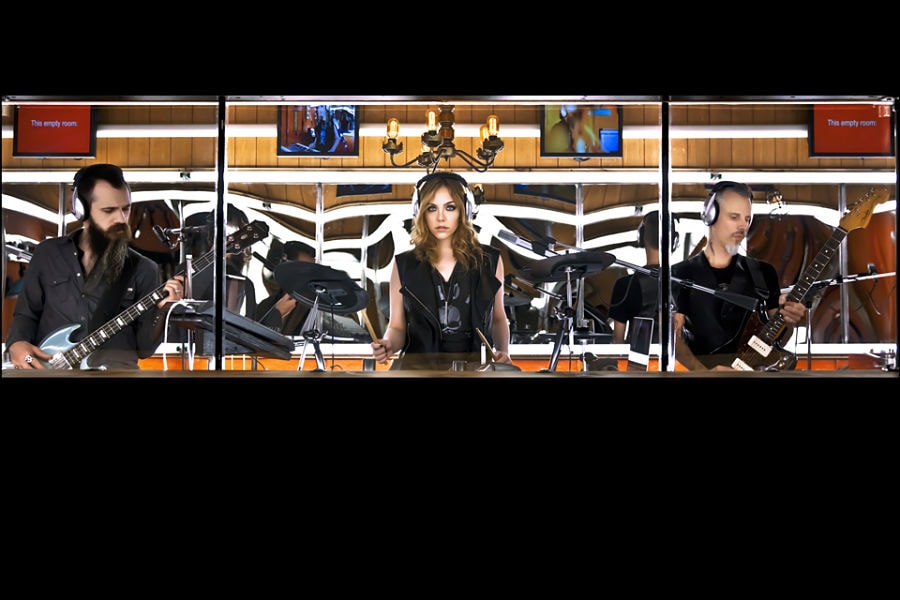

Not forcing audiences to be alert and on edge is also an emphasis in My Voice Has an Echo in It (Jan. 7–11) from the interdisciplinary collective Temporary Distortion. The piece blends art installation, concert and multimedia by having four performers stand in a 24-feet-by-6-feet wide sound booth and perform original music and spoken word for six hours, while audience members—no more than 24 at a time—cycle through by putting on one of 12 sets of headphones available.

“It’s a durational piece for us but not for the audience,” says TD founder Kenneth Collins mere hours before the show’s first run; he plays electric bass and sings in the piece. Indeed, audiences can leave whenever they want and they can come back; the show is free and open to the public.

“It was really a model for how to accommodate the audience and give them the type of experience we wanted them to have. You can come and watch it for 20 to 30 minutes and have a totally fulfilling experience of seeing the work,” he says. Though in previous runs of the work in France, some viewers have stayed for as long as four hours, Collins points out that staying the whole time is not necessary: “It’s not the type of viewing experience that’s ideal for the work.”

The piece was born out of a desire to provide audience members with a front-seat view of a live performance; the six-hour run time came from wanting to play to as many people as possible.

“For me as an audience member a lot of times, especially for shows that are general admission, I start to get a certain anxiety of, Am I going to get stuck in a bad seat? Because it can really make and break the experience the piece,” says Collins. “To be able to walk to one spot, put on a pair of headphones and watch the show for a while, and then decide you want to go to the other side of the box, and change your perspective—it’s really about providing that kind of freedom for an audience.”

The durational aspect of these works doesn’t seem to be a deterrent for audiences. Mac will be performing History of Popular Music: 1900–1950s in two three-hour chunks from Jan. 13–23 before his six-hour show on the 25th, but the six-hour marathon version was the first performance of the run to sell out. Because of its limited occupancy, reservations are recommended for My Voice Has an Echo In It.

There seems to be hunger for theatrical long-range events, in other words, and artists like Mac and Collins are happy to fill it.

“It’s possible that it’s a reaction to the shortened attention span that I think we all have, and this need for sort of constantly shifting stimulus,” says Collins. “People can’t seem to sit down at a table together—if there’s a lull you start to see the phones come out. I think there’s a need for some sort of deeper, immersive sort of experience that we’re sort of missing now. We’re not seeing 6-, 12-, 24-hour films coming out. We’re seeing 6-, 12-, 24-hour live performances. I think that says something.”

Indeed, going to a live event and spending anywhere from four hours to a whole day with it is a commitment, perhaps even a necessary one. “People want to see the durational part—they want to experience something outside the norm,” says Mac, who is no stranger to works with a long run time. His Lily’s Revenge ran five hours. And in 2016, Mac plans to undertake a 24-hour durational theatre performance that will sum up the last 240 years of popular music.

“People go to work all day for 8 hours, and I think sometime it takes more than a 90-minute, intermissionless show to break you out of that pattern. I think sometimes it’s nice just to spend more time with art than we do with survival. It’s a different kind of consideration and a different kind of muscle. It’s about breaking patterns,” says Mac.

Mac likes to use the word ritual to describe the work, and his work with the History project certain has a ritualistic aspect, not only for him but for audiences, who can revisit the project over the course of its multiyear development cycle; Mac says he will continue to perform long and short pieces of it throughout 2015 and 2016.

“I like to joke that the ritual is getting together and being part of the piece. And the sacrifice is the audience,” says Mac.

Hmm—that sounds vaguely bloody.

“There’ll be blood, definitely,” he responds with a laugh.