“Lobbying”—it’s a practice associated with special-interest groups, right? The word’s more literal meaning, though, refers to the ancillary space where all kinds of group interaction happens—a space nobody’s more familiar with than regular theatregoers.

Lately there’s been a kind of revolution in the function of that space, perhaps in a performance venue near you. Around the country and beyond, theatre companies have begun giving audience members ways to directly engage with themes and ideas relating to the piece they’ve come to see—as soon as they arrive at the venue.

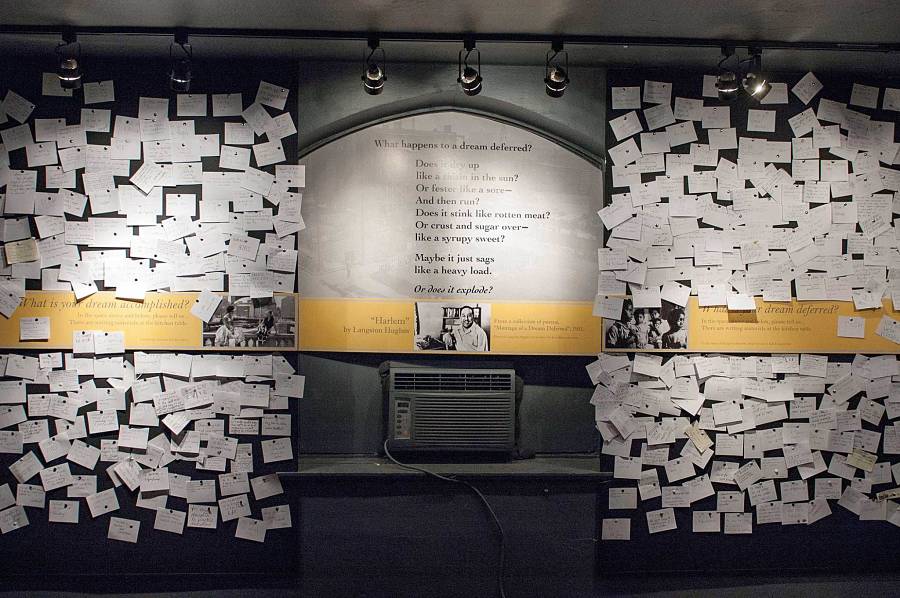

Theatregoers have always had an opportunity to seek out supplemental content before entering the auditorium—maybe by reading about the play’s historical context or the author’s career, or by checking out photos of past productions or design renderings. But now, depending on what’s playing and where, theatre patrons might find themselves sharing a personal secret on a Post-it note, dropping a marble in a jar to vote on a hot-button issue, or even labeling parts of the human anatomy. A variety of U.S. performing-arts organizations—from Center Theatre Group in Los Angeles to Signature Theatre Company in New York City, and many in between—have undertaken informational, sometimes interactive strategies situated in the lobbies of their theatres.

One Midwestern flagship, Steppenwolf Theatre Company of Chicago, is a pioneer of interactive lobby design. Like a lot of theatres, Steppenwolf has long provided show-related material in its lobbies, but in recent seasons the company’s vestibules have contained more and more varied interactive content. The company began consistently doing this type of lobby work in 2011, based on the same impulse that led to the post-show conversations following every performance. Artistic director Martha Lavey explains: “We use the presiding metaphor of the public square to talk about what a theatre can be”—namely, a collaborative effort in which artists and patrons are equal stakeholders.

Before Steppenwolf attendees took their seats for Clybourne Park, for example, they encountered multiple interactive stations, including a wall that invited them to indicate where in Chicago they did or did not want to live by placing color-coded Post-it notes on a large map of the city. The experiment was a success.

“As we continue to design displays,” posits director of new-play development Aaron Carter, “the question we ask is how to best prepare the audience for the experience that they’re about to have.”

An emphasis on collaboration underlies the preparation process: Creating lobby displays may involve several departments, including staffers from the artistic office, marketing, front of house—and sometimes the director, the designers and the playwright. Despite involvement from this skilled team, the project presents the rare chance to create a product that isn’t neat and tidy. “We have a growing appetite to be a little rough around the edges with interactivity,” Carter observes. “We’re very precise in our presentation of our performances and our marketing materials, where there’s a high level of polish. Part of what helps start us on the path of audience interactivity is the willingness to be a little messy around the edges, so that we can experiment quickly and try new things.”

Such experimentation isn’t limited to large-scale institutions—TimeLine Theatre Company, a smaller organization in the Windy City, has enthusiastically implemented similar strategies. Artistic director PJ Powers recalls the origin of the practice: The lobby display for Tesla’s Letters in 2007 “included a more elaborate, immersive, museum-like design, and it set a new bar for what we do. Now, with each production we consider our lobby space in the same way that we rethink our flexible black-box theatre—as a blank canvas to be transformed, reconfigured and reimagined so that the audience steps into the world of the play from the moment they cross through the lobby doors.”

This goal developed into lobby experiences that permit theatregoers to interact directly with the installation, starting with 2013’s Concerning Strange Devices from the Distant West. “Audience members could write and pin on a wall what they thought of a certain image,” recounts Maren Robinson, who has served as dramaturg for a number of TimeLine productions (although not that one). “They could also take their own photos of the lobby and post them on Instagram and Twitter, since photography is a theme in the play.”

Social media and technology have played a prominent role in the lobby designs at Washington, D.C.’s Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company. There, patrons are encouraged to use a show-specific hashtag when visiting different stations of the lobby environment. For Woolly’s staging of Marie Antoinette in September and October, the lobby design featured projections and a customized iPad app, and even fostered digital engagement in the more analog activities. The lobby work for the play—a fresh yet grim retelling of the story about the 18th-century French queen—matched the tone of the piece while aiming to make audience members feel complicit in the action of the play.

“For this particular production, we played with the idea of a dark carnival,” remarks connectivity director Kristen Jackson, “creating this communal experience that’s perhaps a little bit morbid underneath.” Jackson’s team expected the hashtag to be most popular with a “face-in-a-hole” stand that allowed theatregoers to playfully simulate facing the guillotine, but social media seized in even greater numbers on the “Queen Toss” game, in which participants threw Barbie doll heads into holes labeled with point values and a current celebrity/political figure.

Woolly has been constructing these lobby experiences since A Bright New Boise in 2011, when interactive lobby design was a key second-season project in its connectivity initiative. Spearheading that effort was connectivity director Rachel Grossman, now a ringleader with dog & pony dc, where she continues her lobby work and acts as a consultant.

Each of these companies employs a combination of techniques—manual and electronic, active and passive—and they all face the challenge of gauging the impact of their designs. “We’re interested in continuing to experiment with our audience’s appetite for both analog and digital experiences,” allows Steppenwolf literary associate Jenni Page-White. “But part of what we have to consider is the low bar for participation and the high bar for participation.” Different approaches to measure the success of lobby design range from counting responses to physically observing which elements generate activity and conversation. Steppenwolf has found that the most effective displays involve a clear prompt that also gives the participant the satisfaction of knowing he or she has completed the given task.

Several proponents of interactive lobby design said they found inspiration in the book The Participatory Museum and the blog Museum 2.0, both by Nina Simon, executive director of the Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History at the McPherson Center in California. Simon’s work has given theatre organizations a wealth of creative tactics for engaging theatregoers before they enter the auditorium.

Across the (cork)board, these theatres emphasize how interactive lobbies help audience members feel more actively involved in the performance event. And there’s an additional layer: These installations bring theatregoers closer not only to the play they’re seeing, but to each other as well.

“At some level, they’re now in a relationship with other people in the audience, even if they’re just looking at what strangers have posted,” figures Steppenwolf’s Lavey. “However gossamer the connection, they’re starting to form a community.”

Russell M. Dembin, a former intern of this magazine, is a dramaturg and editor in Austin, Tex.