“I never thought that my life as an artist and my life as a teacher could be the same thing,” says Rachel Lee. A devoted 26-year-old educator, Lee frequently “taught on the side” while studying for her B.A. in musical theatre at the University of California–Los Angeles, but it wasn’t until she graduated and moved to New York that she realized her passion for theatre and education could be one job: teaching artist.

Most teaching artists fall into their freelance careers without a clear title or job description, it seems, and their work defies a simple, single explanation. The founding editor of Teaching Artist Journal, Eric Booth—the man known as “the father of the teaching artist profession”—offers a flexible definition as a starting point: “A practicing professional artist with the complementary skills, curiosities and habits of mind of an educator, who can effectively engage a wide range of people in learning experiences in, through and about the arts.”

In a traditional model, an arts organization hires a teaching artist on an as-needed basis to provide arts integration residencies in underserved schools and community centers; to teach after-school arts programs; or to host preshow workshops and postshow talkbacks at theatres. But teaching artistry encompasses a wide array of community engagements—from writing musicals with teens in juvenile detention centers to advocating for voices of the elderly in civic practice—and the work is often driven by an impulse for social change.

Teaching artists continually challenge the old adage that “those who can’t do, teach.” Consider Forrest McClendon, currently starring in The Scottsboro Boys in London, who spearheads in-classroom workshops associated with the show and teaches after-school workshops for at-risk youth. Or musical theatre composer Anna Jacobs, whose work has been performed at Connecticut’s Yale Repertory Theatre, Australia’s Sydney Theatre Company and Connecticut’s Goodspeed Musicals. “If I was the most famous Broadway composer in the world, I would still choose to be teaching,” Jacobs declares. “I’ve noticed that I’m not a happy, balanced person when I’m going through periods where I’m only doing one or the other. I need to exist in a life where I am writing and teaching simultaneously.”

Many teaching artists begin simply as artists, having studied dance, music, theatre, visual arts or another artistic field through high school, college and possibly graduate school. As they embark on a professional career, teaching becomes a natural extension of their artistry, to the point that the two undertakings are inextricably intertwined. Rather than identify primarily as a “teacher” or an “artist,” “teaching artist,” or TA, is becoming a recognizable vocation.

NYC-based theatre TA Heidi Stallings quips that her job encompasses “the two professions that are the most unrespected or beleaguered in our country.” But teaching artists are hard-working, passionate professionals. “There’s such a hustle to it that it really keeps you engaged and alive and ticking,” says Joel Esher, an NYC-based TA for the Metropolitan Opera Guild and Disney Theatrical Group.

Because many teaching artists begin with a background on the artistic rather than the educational side, professional development workshops and conferences are key to their ongoing training. Many theatre companies offer professional development sessions that focus, for instance, on Common Core State Standards—a set of academic criteria and learning goals in mathematics and English language arts/literacy that detail what a student should know by the end of each grade—or on specific populations, such as students on the autism spectrum or English-language learners.

In addition to being the program head of a critical literacy program at Children’s Theatre Company in Minneapolis, Maria Asp teaches courses in “Performance and Social Change” and “Critical Literacy, Storytelling and Creative Drama” at the University of Minnesota, which is required training for her teaching artist cohort. Universities across the country are increasingly expanding their course offerings in educational theatre for both graduate and undergraduate students; New York University, for instance, recently developed a new Undergraduate Certification Program in Educational Theatre that teaches students to apply their artistry in schools, community centers and theatres for young audiences.

Michael Sample of Project Creo, an international network of arts programs that aims to inspire “love and positive change within individuals and their communities,” credits his colleagues as one of his greatest educational resources. “One fun benefit from the sheer exposure to various teaching styles and approaches is that I am able to grow my own ‘bag of tricks’ as a teaching artist/educator,” he says. Even auditioning for teaching artist companies—teaching an excerpt of a lesson plan, for instance—helps with professional development. “The companies bring in the most amazing people,” says Lee. “I have stolen so many lesson plans from being in the room with these people who are offering up their pearls of wisdom.”

Major arts presenters across the U.S.—such as D.C.’s Arena Stage, the Brooklyn Academy of Music, Center Theatre Group in Los Angeles, Disney Theatrical Group, Chicago’s Goodman Theatre, and the Metropolitan Opera Guild and Roundabout Theatre Company in New York—maintain a roster of teaching artists who visit underserved public schools every year to create theatrical ensembles and to implement in-school programming that uses the arts to support curricular goals in subjects ranging from English to social studies, math to science.

Rachel Lee, who is a teaching artist for Disney Theatrical Group and Marquis Studios, calls this method of arts integration “sneak-attack learning.” Teaching artists do not replace full-time classroom arts teachers; rather, their lesson plans creatively reinforce curriculum goals, such as identifying literary themes, citing evidence to support textual analysis and making personal connections with a text. When possible, programs often send a TA to a school multiple years in a row, so they become an active part of the culture.

Organizations such as Disney and the young-audience-focused New Victory use team-teaching artists to model positive collaborative relationships, and Roundabout’s TAs partner with a classroom teacher for the same purpose. A teaching artist is in a unique position to engage students in a different way from the classroom teacher, according to Ellen Warkentine, an itinerant theatre teacher with the Los Angeles Unified School District. Although it can be more difficult to build deep and long-term relationships, Warkentine engages students on a creative level as a collaborator, which “creates so much more freedom for students to express themselves.”

“The goal is always to have a space for young people to create art that generates conversation,” says Ashley Forman, director of education at Arena Stage. Arena’s Voices of Now program establishes devised theatre ensembles in underserved partner schools and community organizations in and around the D.C. metro area, such as the Wendt Center for Loss and Healing, and Fair Girls, a nonprofit for survivors of sex trafficking. The diverse ensembles are all taught the same specialized theatre and movement vocabulary, so there is a unified style to every Voices of Now play. After a series of drama workshops and a day of casting, the ensembles create original productions to be performed at a five-day-long festival on one of Arena’s professional stages in the spring. Every play is followed by a talkback, “because the play is the beginning,” says Forman, who refers to every participant as an artist and empowers the students as experts of their own experiences. Oftentimes, these “100-percent autobiographical” plays raise issues that the community isn’t even aware are present in their own backyards.

Unlike many programs that emphasize artistic process, Voices of Now equally emphasizes product, because “the stronger the product, the more likely the audience will be to listen to what the artists onstage are saying.”

Forman has even witnessed the transformation of student artists and their families through the young students’ art. The Advocacy Ensemble’s play in spring 2014, for instance, included a transgender artist performing a monologue about the lack of support in the trans community in D.C. Ashley later received an e-mail from “a totally different artist in a totally different ensemble” whose father had been homophobic her entire life. “My dad was completely transformed after that performance,” the student wrote. “He sat my family down after dinner and told us he was wrong.”

Joy Lamberton-Arcolano, founder of Playhouse Education in Watertown, Mass., recalls one of her earliest moments as an in-school teaching artist with Shakespeare & Company in the Berkshires. In a session about Julius Caesar, a fourth-grader raised his hand and pointed out that Caesar and Marcus Brutus were friends when they were in school; he then turned to his best friend and said, “I will never kill you for anything.” “Then these fourth-graders proceeded to have a very high-level discussion about when it is okay to kill somebody for the greater good,” Lamberton-Arcolano remembers.

“We’re always talking about access [to the arts]—who has it, who doesn’t—but every child is having trouble accessing themselves,” Lamberton-Arcolano says, emphasizing that her work at private schools is just as essential as her work in rural, ethnically diverse and impoverished public school settings: “On a fundamental level, I just want to engage more students.” Especially when casting for a large-scale show with upwards of 50 actors, she makes a point to place students in roles that will challenge them, rather than “pick the two that are the most talented and give them a 90-minute showcase of how wonderful they are so everyone can clap for them.”

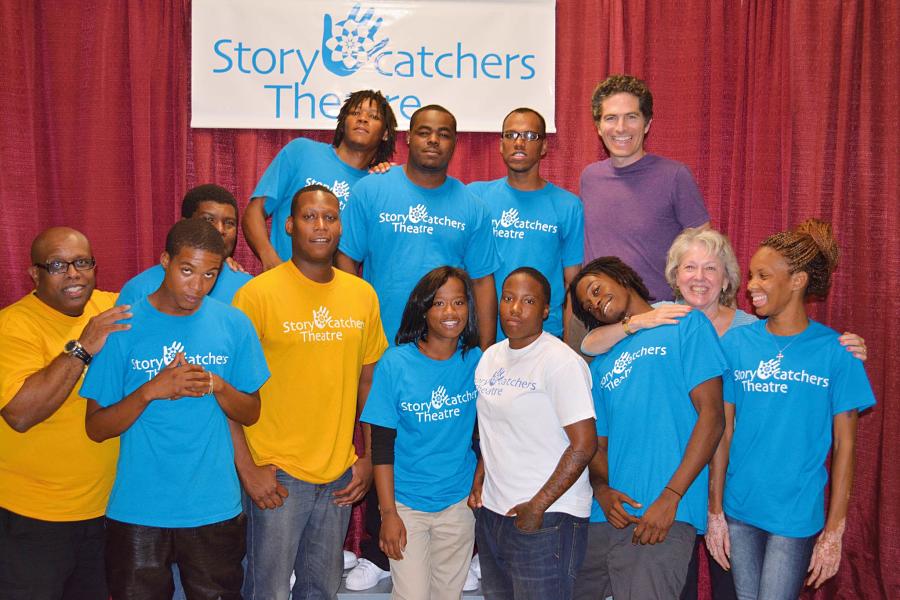

Not all teaching artistry takes place in a traditional classroom or after-school setting. For Cheryl Coons, a program manager at Storycatchers Theatre in Chicago, performance can make the difference between seeing a child as a list of charges and as a human being. Storycatchers Theatre works with court-involved and incarcerated youth in detention facilities and juvenile prisons, coaching them to write original stories from their lives, to improvise and workshop dramatic scenes, to compose musical theatre songs in a “hip, edgy musical style,” and then perform these musical plays for fellow residents of the facilities, along with teachers, family, friends and the community. Sometimes attorneys and judges join the audience, enabling them to see the youth they are prosecuting in a different light. “A kid writing about becoming a father at age 12, writing about how his son is the best part of his life, gives you a different perspective on him,” she posits.

Adult mentors like Coons are called “kid whisperers” at the Chicago facilities, because they have a knack for reaching youth who are otherwise disengaged. She has seen students go from being on suicide watch to being leaders in their Changing Voices program, which employs youth who have recently left detention centers to musicalize their experiences. Changing Voices is part of an ongoing aftercare system to increase the likelihood of successful reentry for court-involved youth. “I never expected I’d be doing this work, and it’s one of the best things that has happened to me as a human being,” Coons says, with feeling. “It’s been a gift that working in the theatre doesn’t always give—really immediately knowing that what you are doing is transformative.”

Improvisation and devised theatre are frequent tools in teaching artistry and theatre for social change. “There’s something about the collision of different perspectives that can occur in a devising practice that’s fairly exciting and unique—particularly if you make a point that your collaborators are diverse in terms of generation and geography, as well as ideology, culture, gender, sexuality,” suggests Michael Rohd, founder of Sojourn Theatre, based in Portland, Ore. While emphasizing that Sojourn and its partner organization, the Center for Performance and Civic Practice, do not practice teaching artistry in a traditional sense, Rohd says they are undeniably creating “needs-based practice.” His company’s 15 ensemble members live in eight different cities and collaboratively create original performances in response to different impulses, contexts, communities and participants.

For example, Sojourn worked for several years with homebound seniors in Milwaukee, aiming “to bring the voices of community elders into conversations about systems and policies.” In Sojourn’s touring show How to End Poverty in 90 Minutes, the audience receives $1,000 from the box office and collectively decides how to fight poverty in their community with those funds.

Proud Theater Company, an ensemble for LGBTQ youth and allies, was also created in response to a specific need in a local community. In 1999, actor Callen Harty was approached by 13-year-old Sol Kelley-Jones to start a social justice theatre group for teenagers in Madison, Wisc. Under artistic director Brian Wild, the program has since spread to five chapters across the state. At each session, the youth discuss what is happening in their lives and improvise scenes based on common threads and themes; they continue workshopping and developing the material right up until show time. “The big thing that we’re teaching, besides theatre and social justice, is how to express yourself,” Wild says.

He is continually astounded by the “complexity of the stories that are coming out of these youth,” he says. “What makes good theatre is the stories that are true and deep. That’s what makes the work that we’re doing so important.”

Since day one, Proud Theater has been an all-volunteer organization. The fact that 60 percent of the adult mentors are former youth from the program is a testament to the company’s impact; the ensemble establishes a safe space for teenagers to express themselves and learn to lead.

“We know we’re at the point where we have to have paid staff,” Wild notes. The truth is that finances are a practical challenge for all teaching artists. In a 2009–10 online survey by the Association of Teaching Artists, 71 percent of respondents made $20,000 or less per year from their teaching artistry; only 5 percent made more than $40,000. What’s more, 87 percent of teaching artists juggled working for two or more organizations.

TA Todd Woodard teaches in New York and New Jersey for no fewer than seven different arts organizations, all of which have their own protocols for curriculum mapping, lesson planning, documenting lessons and submitting project tracking reports and payroll. “Besides being a teacher and an artist, I’d say my position also requires me to be my own office manager, accountant and agent,” he says.

The commute is another inherent challenge in making a living as a TA. “Teaching in four out of five boroughs every week, the train is your best friend,” according to NYC-based Lee. In areas without public transportation, the cost of gasoline—and the hours spent in the car, not working—add up. Christopher Albrecht drives among three different public school districts in Los Angeles: Cypress College, a local dance studio, and professional gigs at Southern California theatres like the Chance. Radhika Rao teaches across a 50-mile radius in the Bay Area, including residencies with Young Audiences of Northern California, San Carlos Children’s Theater and the San Francisco Shakespeare Festival. Even with her Ph.D. from the Harvard School of Education, Rao wonders how long this career is sustainable.

Teaching artists are no longer satellites working independently—a sense of professionalization and community is growing among these passionate, artistic educators. One of Lamberton-Arcolano’s most exciting moments of connection occurred during a summer program at Emerson College in 2014. During “trajectory day,” every teaching artist took the first 15 minutes of class to tell the story of his or her own development in the arts—and a young man “from a teeny-tiny little town way up in Vermont” found his calling. “Ryan was the first young person I had ever heard say, ‘I want to be a teaching artist,’ and it hit me so hard,” Lamberton-Arcolano recalls. “And then the next words out of his mouth were, ‘I didn’t even know that was a real job until three months ago!’”

Dr. Sarah Taylor Ellis is an NYC–based teaching artist. She is currently revising her dissertation for publication.