MADISON, N.J.: Paul Barry began his career as an actor. In time he became an actor-manager, which means that he also became a producer and director; but he always remained an actor at heart. Directing, he once confessed to me, was “a lousy job”—hours of hard work, research and casting that are not a great deal of fun. And, of course, you don’t perform the play; you turn it over to the actors. He never shared his thoughts about producing with me.

But then, his wife Ellen relieved him of many of those responsibilities. She was as excellent a manager, fundraiser and producer as she was an actress. I think that Harry Keyishian, the Shakespearean scholar, rightly described their partnership: “Paul ruffles feathers and Ellen smooths them out.” They suited each other perfectly, and they knew how to make things happen.

Paul founded the New Jersey Shakespeare Festival in 1963 and headed it, through good times and hard times, until 1990, a period of nearly three decades. That is an extraordinary and rare achievement for any actor-manager. In 1990 he completed directing the entire canon of Shakespeare’s plays, including Two Noble Kinsmen, an even more extraordinary achievement. During those nearly three decades he, with Ellen at his side, created hundreds of work weeks for actors, giving those of us fortunate enough to have worked with them the opportunity to sharpen our tools by playing for audiences in a repertory from some of the greatest plays ever written, with Shakespeare’s plays always at the core of the repertory and the heart blood of the repertory.

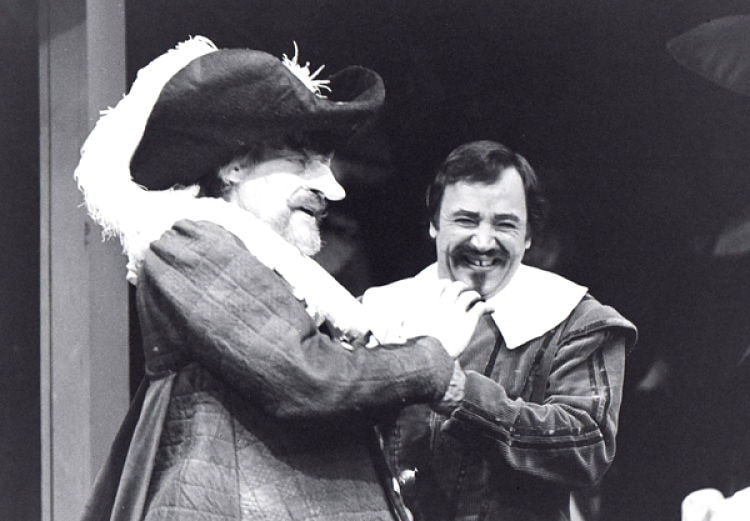

I appeared in many plays with Paul, but I think Cyrano was the best thing I ever saw him do. When I told him that years later, he said Cyrano was the kind of great part that plays itself and gives wings to the actor lucky enough to play it. He wisely used Brian Hooker’s blank-verse translation of the play—a minor classic on its own. He directed the play, choreographed the swordplay, and played Cyrano. There’s a job for you!

The duel with Valvert was the best I have ever seen. Paul’s Cyrano disarmed Valvert, sending Valvert’s sword soaring into the air, and then caught it—I saw him do it every night. He never missed—and gallantly returned it to Valvert to finish the duel. He played the Man fallen from the Moon with a middle-European accent to waves of laughter and great bravado, but underneath the bravado, and equally as important to Cyrano’s character, Paul retained throughout a self-effacing vulnerability that I have never seen in any other Cyrano. It was a great personal success for him.

Late in his life, after years of experience with the plays, he concluded that Shakespeare’s plays should be played uncut, and he began to do them uncut. He had always, for the most part, had his designers retain the balcony and inner-below playing areas of the Globe as part of their designs. That gave the action of the plays fluidity and momentum, and under his direction we played the uncut Hamlet of the Folio plus “How all occasions do inform against me” in three hours and twenty minutes with two ten-minute intermissions. We played Julius Caesar in two and a half hours with one intermission.

The years I worked with Paul were very important in my career. I loved the work, and I loved him. I also admired him and what he achieved. But I never admired him more than I did during his final years. They were tough; but so was he, and he faced them with great courage and fortitude. It is typical of Paul’s indomitable spirit that during those difficult years he wrote A Lifetime with Shakespeare, an excellent book to be read and reread. It is as valuable a legacy to actors as the company he founded and launched more than half a century ago.

Well done, Paul! Well done, indeed! Requiescat in pace.