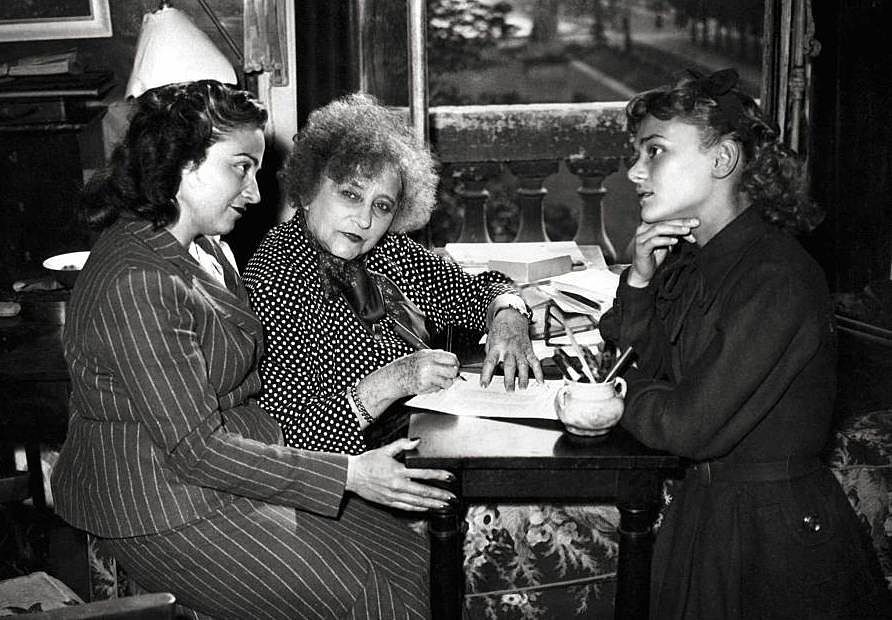

She is best known now as the original author of the novella Gigi, on which the Broadway play and the musical film were based. But the story of Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette, the daughter of a French army officer from Burgundy, began in earnest with her time as a semi-scandalous music hall performer in Paris around the turn of the 20th century. She later wrote the libretto of Ravel’s opera L’enfant et les sortilèges and had her first big success with Chéri (1920), a novel about a retired courtesan and her young lover (which the American choreographer/director Martha Clarke would later adapt for the stage). She would go on to publish 50 novels, but none so well known as Gigi, which sealed Colette’s legend in at least one other significant way: The author is directly credited with discovering the original creator of the role in its Broadway incarnation, a young Belgian/English wisp named Audrey Hepburn.

The following text is drawn from two lectures that Colette gave about her own life in the theatre, one delivered on Feb. 8, 1924, the other on Nov. 15, 1924, well before her international fame was secure; they stand as an archetypal document of a theatre person catching the “bug,” first as a performer, then as a dramatist.

A few notes for context: Colette jokes about her thick accent, acquired in the province of Burgundy, which was considered a liability in French theatre. She also mentions several figures from French drama who are no longer generally familiar: George Wague (1874–1965), a famous mime Colette performed with, notably in the play La Chair [Flesh]; Christine Kerf (1875–1963), an actress who also appeared frequently with Colette; Sacha Guitry (1885–1957), an actor, director, playwright and screenwriter who wrote more than 120 plays; the Tarride family, which boasted several actors, including Abel (1865–1951), Jean (1901–1980) and Jacques (1903–1994); Firmin Gémier (1869–1933), a famous actor and director who created the title role in Alfred Jarry’s play Ubu Roi; Marguerite Moreno (1871–1948), a renowned actress and close friend of Colette’s; and the Fratellini, a circus family with exaggerated makeup.

Colette also refers in these lectures to a prank that actors play to make one of their troupe break out laughing onstage, called “corpsing” in the U.K. because it is sometimes done by having an actor secretly wink or grin while playing a corpse.

This material is excerpted from a new Colette collection, Shipwrecked on a Traffic Island and Other Previously Untranslated Gems, which was published in November by State University of New York Press. —The Editors

From Behind the Set

Theatre now conducts itself in the world a bit like a little woman newly arrived in polite society who doesn’t know how to sit down without making her skirt puff out too much.

At the time when I, as they say, strutted the boards, right away they treated me indulgently as a sort of foreigner without a future there. When I made my debut as a playwright, the critics didn’t want to crush in one fell swoop and forever this eccentric who, no doubt, would not repeat the crime. So I benefitted from the general indulgence that didn’t imagine that this foreigner and this eccentric might come to them, not only as a foreigner, but as a “spy”; I would even say (although the word is too strong) almost as an enemy.

The first tableau [I acted in when I was learning to be a mime] featured a village festival. An unknown man, a stranger, walks down a mountain footpath, interrupts the farandole and the joyful dancing, while the peasants ask in sign language, “But, stranger, where are you from?” Which the poor boy was supposed to answer with hand gestures: “I’m from a faraway land where the young women, on Sunday evening, dance with red scarves wrapped around their hair buns!” I don’t know if I was just a hopeless novice, but I could never understand how one could express in gestures “Sunday evening” and even “the red scarf.”

[The music hall] is where I surprised the magician at his trick; that’s where I felt for the anguish of the trained animal; that’s where I discovered the secret panting of the acrobat and the contortionist, of the snake-man whose contortions—even though he did them on a daily basis—still tortured him. That’s where I happened to hear the well-concealed moans of the strong man, who one day caught his bronze cannon slightly at an angle and, on the nape of his neck, while smiling and waving to the audience, hid a wound he had just received and which he was groaning from quietly. While you, you were applauding how graceful they looked, I, from the other side of the curtain, I took in the convulsive grimace, and the muttered blasphemy, and the strain masked for you. At that moment, I saw the glittering sprite, who had just finished whirling and flying in front of you and me, return to the shadows behind the set, dragging two injured feet. It’s at that moment that I saw, behind the set, all the color drain from the face of an adolescent, who in just a second onstage was about to hold out with a frail hand an ace of hearts as a target for a rifle, and I could hear on his chest the tinkling of charms and good-luck medallions because they were shaking so hard. And I saw the beautiful Hindu snake charmer change her costume, right next to me, with the innocence of a naked child. You, you saw them onstage, but, during this time, it was I who heard alone the rustling of oiled silk made by snakes waking in their crates.

It was during this time that one day, behind the set, a wolf that was also waiting his turn reached his mouth between the bars of his cage and seized my hand as it was dangling down, and since he didn’t clamp his jaws, I believe that on that evening he treated me as his friend, and as a fellow performer.

That was where I saw a beautiful classical dancer arriving from the other side of the curtain, and without taking the time to unlace any part of her costume, ran to the dressing room where her infant, who was four months old, was waiting, lying in a compartment of a trunk; and I can still see that beautiful girl who nursed her infant in a dancer’s pose—that is, putting all her weight on one foot, with her skirts in a wheel around her—and I see the magnificent gesture that she made in pulling her beautiful breast out of her bodice to give it to her child. And she nursed the infant like that—all her weight on one foot, with her hands pulled back behind her—because she didn’t want to touch the baby with her hands all full of makeup and so cold. It’s one of the most noble images that I took away from my life in music halls.

It’s there that I saw all sides of a self-enclosed and mysterious world; it’s there that heroism is naïve and joy is childlike.

For you, these memories are nothing but a passing image; for me, these images have taken on the power of a state of the soul. So here are some that I hope you will allow me to mention to you:

My friend George Wague, Christine Kerf, and I, we had to get on a night train. It was on a black night, in a rainy town. It was 12:30, after midnight; all the lights had been turned off, the show was over, and we were walking across the stage, carrying our luggage. The stage was dark and sliced only by a single beam, because of the light they turn on at the front of the stage when the show is over, which they call the “ghost light.” And in this darkness, on this stage, in this fairly sinister blackness, two Chinese people were repacking their luggage, like us, the diminutive and fragile luggage of prestidigitators, consisting of a few boxes, stacked together, of artificial flowers, and their yellow faces expressed an incurable melancholy.

They didn’t speak a word, and all the light on the stage seemed to come, at that hour, from a flight of doves, trained doves who took their exercise like prisoners and who, under the roof of the theatre, wheeled around and around and came to roost on the shoulders of the ones whom I called their tormentors, since nothing is sadder than the fate of the trained animal, especially when it’s a dove. They alighted there tenderly, cooing. They were doves of the type that is pinkish white, with a little black necklace; then they whirled around the ceiling of the stage exactly like a flight of rose petals from a game of she-loves-me-she-loves-me-not.

For you this is only a memory, a little optical memory. For me, this image has remained symbolic—melancholy, with no escape—of unassuaged tenderness, of resignation. So true is it that once you are marked for literature, literature insinuates itself perhaps into the simplest of images, but I can’t say that this image is only about literature.

The Strange World of Actors

I can’t keep secret from you much longer that when it comes to the theatre, I didn’t have much success as an actress, either in Paris or in the provinces. I can say now that Paris didn’t understand me. No, Paris didn’t understand me, and the drama critics, those awful drama critics who are now my colleagues, testified that I hadn’t lost my Burgundian accent, that I rolled my rs when speaking; you are my witnesses, though, since you’ve heard me speak, that this is completely untrue, and all that is obviously just a conspiracy!

But in the end, there had to be something more than that criticism, which was ultimately benign, to keep me in that world I didn’t know: There was my incurable and untiring curiosity, the bewilderment and the stupor that I felt in getting to know, on that side of the curtain, a type of humanity that resembled in no way what I had left behind at the music hall.

This strange world of actors, this world where professional solidarity is a magnificent thing but where individual ferocity is no less magnificent and in a sense primeval, the glimpse I caught of it astonished me. And since that time, because I’ve stayed in touch with it, it never ceases to amaze me. Seen from that side of the curtain, the world of the theatre is a mythical land where nerves become a focus of discussion as if they were an occult power or a company of elves.

It’s a world where rivalries manifest themselves in all sorts of ways, and not only in the competition for parts, but also in the color of a dress worn onstage, or a jewel, or a carriage—in fact, anything that can become a subject of rivalry. It’s a world that sustains itself on pride, and even vanity, but it’s also a world where pride in the profession comes first—in short, above pride plain and simple.

It’s a world, finally, which it must seem to you that I’m speaking about with an animosity so unjust that you can easily recognize a bitterness of the sort that follows great disappointment. Thank God, it’s not quite that! I will never forget the modest debuts I made in the theatre; I will never forget that I was well compensated with pleasure and fun. It’s enough for my artistic vanity that I appeared in the cast, in a minuscule theatre, of a comedy by Mr. Sacha Guitry called Horsehair. Does anyone here remember Horsehair? No? There you go, you’ve forgotten me already! Impossible!

It was a sweet little play, where its very young author—very young at the time, since I’m speaking of about 14 to 15 years ago—had already incorporated his well-known humor and young man’s imagination into the plot. In fact, the play had all it needed, except the seven or eight last lines that came right before the final curtain. We had all of one week to get the play ready, and every day we protested to the author that we needed the end of Horsehair—the last strands of this horse’s hair. Each time he promised us we would have it the very next day. In the end, on the day of the final afternoon rehearsal, before the final dress rehearsal that night, we still didn’t have the final lines, so we were waiting for the author who was supposed to bring them to the afternoon rehearsal. We waited for him for an hour, an hour and a half, and more. Finally, at 5 p.m., the director rushed away in a taxi, we were all in a mad panic, and he came back an hour later and transmitted the answer that was given to him by a servant: Monsieur Sacha Guitry had left that very morning for a two-month-long trip to Holland!

You can imagine the deflation of the morale of the actors, poor actors that we were! We did what we could, we inserted what they call action, we added jokes, we even added a bit of dance, we included humor, even a spritz of a seltzer bottle that I pointed with sure hands in the direction of the orchestra seats. Obviously that was all very nice, but it wasn’t the same as the few lines that the author was supposed to add to Horsehair. But it wasn’t because of this that 14 days after the first performance, the manager of this minuscule theatre ran off with the box-office proceeds, and at the same time, our salaries, which were just as minuscule.

I experienced a sharp sense of disappointment from a financial standpoint, but do you think I lost my sense of humor and my curiosity? You don’t know me if you think that. I gained, on the contrary, a sudden sense of confidence in my gifts, since that accident resulted in my suddenly being anointed as an actor. I was mistaken. Experience showed that. But I consulted the experts, I resolved to work hard and I went to get advice from Tarride.

Tarride was very sweet. How could Tarride not be sweet? He’s a delightful boy. He listened to me with much kindness, and he said to me, “Don’t you think, that of all the arts, you’d be best suited for pantomime?”

I didn’t want to contradict Tarride, so I went to see Gémier. Gémier was also charming. How could Gémier not be charming? He said to me, “What in the world was that dance you did out there onstage? I’m telling you, what you need is some good choreography!”

Armed with these excellent suggestions, I went to see my friend and teacher, Christine Kerf, to inform her that I would become a dancer. She got straight to the point, with that trace of a Flemish accent that drifts back into her voice sometimes and that I find delicious: “Yo, yo, yo, what in the world are you thinking! Listen, you’re not young enough to start dance. Do you think you can start dance seriously at your age? You have to start very young! You don’t even know how to do a jump. Dance isn’t going to work for you.”

Thus encouraged, I didn’t lose my equanimity, nor that untiring curiosity that got me from wing to wing, from dressing room to dressing room, from the fireman’s stall to the prompter’s box, and from stage to stage, until—I didn’t foresee this!—I ended up in a puppet show, where the author of the drama, in front of the stage, surveys his play, and his own play comes into being, patiently taking shape.

A Dangerous Attraction

At times there is definitely a sort of courage in literature, pared down to its basics: You pit yourself against a blank page, with a character you have just created and who, nevertheless, already governs in her own way her own life in the novel, and imposes on your brain her ghostly vitality, the whimsy of a specter born in the moonlight. Obviously, there is a sort of prideful pleasure in a duel of wits with this creature from your brain who already has a will, in the triumph over her. But what is the equivalent of this great pleasure when it comes to theatre? Because to knead for the stage, on the stage, living beings, speaking beings, mulish or docile, ungrateful or magnificent, perfectible or incurable—what attracts you, I repeat, what binds you to the theatre, is this prideful pleasure. It consists in saying to an actor or an actress, in a rehearsal:

“There you are, with your grayish-greenish suit, or maybe your threadbare jacket, there you are with your 50 years, there you are with your impoverished hair, with your dyed hair, your rheumatism! Still, you will be the irresistible young man, you will be the virgin in the springtime of her life, you will be a courtesan with no bounds, you will be a mother torn apart, and it will be my fault, and it will be my work, and I will knead you with my own hands, and you will rehearse 100 times your attempt to make yourself cry spontaneously, your attempt at crystalline laughter, your drunken faint, you will rehearse as many times as I like until I’m content and until I tell you, ‘That’s good—now do it better.’”

That is the true attraction of the theatre; it’s a satisfaction that’s intense and yet never exhausted that theatre offers to our instincts of a little Nero of the republic. I have tasted that autocracy, and I assure you, the way it binds you to the theatre is much more dangerous than success!

A Bernhardt Conspiracy

You’ve seen that childish and juvenile infectious laughter on the stage that seizes one actor and then spreads to another and then another. Every actor at one time or another becomes the target of a conspiracy: We’re going to make her laugh, and we’ll get her, they say, we’ll get her before the end of the play. This conspiracy spread and went as high as Sarah Bernhardt herself. She was acting, at this time, in The Witch by Sardou. Pretty much everyone, I think, wanted more or less surreptitiously to make the great Sarah laugh onstage, but Sarah, with the equilibrium that she was famous for, with her willpower, was too dominant, there was nothing that could make Sarah burst out laughing onstage. She was completely in her art and didn’t hear anything else. Nevertheless, in the scene of the Tribunal of the Inquisition, she couldn’t hold out.

I’m going to set the scene a little. On one side, the Tribunal of the Inquisition; on the other side, the judges are presiding over our dear De Max; on the ground, supplicating, prostrate before them, holding up her beautiful white arms, a perfectly innocent witch who is none other than Sarah herself. A witness for the prosecution enters on this side: Marguerite Moreno, made up as a witch: hooked nose, black, in rags, supported by a stick, in short, the traditional witch—oh, so evil!

One night, Marguerite enters from that side of the stage. She had made up the right side of her face the way she usually did, as an old witch, with wrinkles, with charcoaled eyebrows. But on the other side, from her nose to the line of her chin, had made herself up in a way that would not have disappointed a Fratellini clown. She has an eyebrow up on her forehead; a red and drippy eye on her cheek; and, even worse, she has a wart in modeling dough with horsehair growing out of it. She enters the set, and the audience can’t see a thing. But the Tribunal of the Inquisition, who are facing that side of her, start to be sick with laughter. The judges lose their composure and De Max is having a hard time keeping a straight face. Sarah, who is on the ground imploring the Tribunal, sees perfectly well that the infectious laughter is winning out, and between the lines of her part she hammers out these words: “You will all be punished, you will all be punished! Infamy! Disgusting!”

She continues with her role, but things do not improve with the Tribunal—just the opposite. Finally, since it’s in the script, Sarah turns toward the awful witch to say to her: “But tell me, miserable witch…” And turning around she catches sight of Marguerite Moreno. That night they got Sarah Bernhardt, and they got her so good that instead of saying, “Miserable witch,” she repeated three times in a loud and clearly audible voice—and you know how her voice could carry—“Miserable Moreno! Miserable Moreno! Miserable Moreno!”

I think they lowered the curtain—but if I add this, it’s not because it’s true but just to have a good ending for my story.

To Act or to Write?

I struggled with my utter presumptuousness, since I was completely new to this profession, so much so that I knew nothing about it. I arrived with what they call “a fresh eye,” and I struggled, for instance, against the craze for the handkerchief in the palm of the hand that the young woman madly in love brings into the first act, and clutches until the end of the third act. I tried to struggle against the fingers hooked into the vest, or the hands in pants pockets, which assure composure in difficult moments for the young lead or the young supporting actor; against the floppy shrugs of the ingenue; and also against the gesture that I saw the ingenue reverting to which is somewhat comical and nervous, and which is fairly new, which I’ve noticed on certain stages and which consists in crooking a finger under the nose because it makes her look like a good girl, and natural. I struggled against all that, all that and many other things, with utter presumptuousness, with unheard-of self-possession. When you’re an actor without talent, you can’t imagine how much you know about what the other actors, those with talent, should be doing or not doing.

After weeks of journeyman acting, of work, weeks of discussions, weeks of bitterness, weeks of lyricism and bursts of enthusiasm, suddenly, since it was a quarter to 9, I ended up entirely alone, there on the other side of the stage, in a little space called the production department, where they store broken lamps and furniture with three legs. I found myself in a solitude where I could no longer hear the sounds of everyday life; the daily work was gone, and so were those whom I had lived with so closely—they had all suddenly left me. I was alone because the actors were practicing their profession, they were performing the play. The director, whom we had had words with during the rehearsals, was also going about his business, in the stage box to the right, and my collaborator, he, too, had gone.

I was utterly alone, and this solitude took a form so bitter, so emotional, that truly, instead of emotion, instead of the type of joy, of nervousness that is all I should’ve felt when thinking about the outcome of that dress rehearsal, suddenly I felt like a person completely alone, completely abandoned—above all, someone nobody needed anymore at all. I was there, alone, with an azalea plant that hadn’t found a spot in the dressing room of the artist it had been sent to—always red azaleas in those situations. I was there, with that azalea plant beginning to wilt, in a state of solitude that was unfathomable and bitter beyond measure. There was nothing funny about it. It was a sensation that caused me more pain than I should permit myself.

After some time had passed, I heard a sort of noise, a weak and distant lapping. I didn’t recognize it because I had never heard it from this location, and after that, another noise, noises of voices, this time voices I knew, and then all the actors came in, I saw my previous life come storming back, I witnessed such a warm onrush, so much affection, so filled with excited talk, with the arms of friends, with rouged mouths, lively faces, even friends who came from the audience, also enemies—all of that flooded me so with that warmth that I was lacking that I suddenly felt myself turning pale emotionally. I felt a shock, a shock that struck so close to my heart that I said to myself:

“How can it be that these actors—all these people whom I’ve only known for three or four weeks—I already love them so much, how can it be that they have become so necessary to me? My God! How I’ve been bitten, how deeply the poison of the theatre has already seeped into my blood, how much I need them, how much I feel that it will be vital, one way or another, to find them again, either them or others! And I can clearly see, I admit, that there is only one way to find them again, to feel their warmth again, their sharp hunger for living that they have passed on to me, there is only one way, and I’m going to do it right away—I’m not going to resist any longer. I’m going to write another play!”

Zack Rogow’s translations from French include work by Marcel Pagnol, George Sand and André Breton. He received the PEN/Book-of-the-Month Club Translation Award, and teaches at the University of Alaska–Anchorage.

Renée Morel is a translator and adjunct professor of French at City College of San Francisco. She founded the popular Café Musée series of lectures on French literature, art and history.